| There lived a king of Benares who, despite all his riches and plenty, still was unhappy. For though he had sixteen thousand wives, he had no son nor daughter. Each and every one of his wives prayed that she might bear a son to him. His main queen, Candadevi, asked of the great god Sakka : "If through my life I have done only good, a son be born to me."

When her plea reached Tavatimsa heaven, the throne of Sakka, king of the gods, became warm, an sign of an injustice on earth. Sakka realized that he had overlooked the virtues of Queen Candadevi. Immediately, from among the deities in heaven he chose the Bodhisatta, who he knew would serve as a model of self-denial for the kingdom of Benares, and sent him down to earth to be conceived in the queen's womb. In addition, to five hundred nobles' wives he sent five hundred more beings to be born as the Bodhisatta's attendants. When the queen felt as though her womb contained a diamond, she knew she was pregnant. She informed the king, and both were happy. Great care was taken until the day of her delivery. Upon hearing the words of the birth of his son, the new father felt paternal affection lighten his heart. At the same time, five hundred nobles' gave birth to infants who were to grow up with the Bodhisatta and serve him. The Bodhisatta was given sweet milk from sixty-four wet nurses selected because of their flawless beauty. After presenting the nurses to the queen the king felt generous and told her he would grant anything she asked. However, the queen postponed her request, as she preferred to wait for the day when she might need it. On the occasion of the naming of the child, the Brahmins proclaimed that the royal son and heir to the throne possessed every mark of good fortune. The king named his son Temiya-Kumaro, meaning 'prince drenched with water', because both his birth and the rainy day on which he was born were very wet.

When Temiya was only one month old, he was dressed up for his first public appearance and brought to the throne of his father to sit on his knee. Many courtiers admired his beauty and murmured their approval. Four robbers were then brought before the king to be judged. Temiya witnessed his father sentence one robber to a thousand strokes from thorn-baited whips, another to imprisonment in chains, a third to death by the spear, and a fourth to death by impaling. The infant Bodhisatta was terrified at his father's apparent cruelty and thought to himself, "A king acts as judge, and so he must perform cruel actions every day. By condemning men to death or torture, he will however himself be condemned to hell."

The next day, awakening from a short nap and looking up at the great white umbrella above him, the infant began to think of what it would mean to be king. These thoughts alarmed him, even more so as he remembered a previous existence in which he himself had reigned as king of Benares for twenty years. As a result of dread decisions forced upon him in the position of king, he had had to suffer eighty thousand years in hell. Now he was destined to become king again in the same city, again to suffer the same fate. This was more than he could bear. As he wondered if escape was possible, a goddess dwelling in the umbrella above him, who had been his mother in a former life, spoke to him :

'Temi my child, let me help you.

You must do as I advise : Pretend to be a crippled mute.

Don't move your limbs or use your voice. Then the people will refuse to crown you king and you shall be free.'

The Bodhisatta at once began to show signs of being different from the other five hundred children. While the others cried out for their milk, Temiya did not utter a sound. For the first year, his mother and nurses noticed with alarm that he neither cried nor slept, moved nor listened, though his body appeared normal. Knowing that he must feel hunger, they tried to force a sound from him by withholding his milk, at times by starving him for a whole day, but to no avail. In his second year, they tempted him with various cakes and sweets over which the other children fought. But Temiya would say to himself : 'Eat the cakes if you wish for hell', and thus abstained. All kinds of foods, fruits, and toys left him unmoved, though other children grabbed greedily for them.  | | The Temiya Jataka -

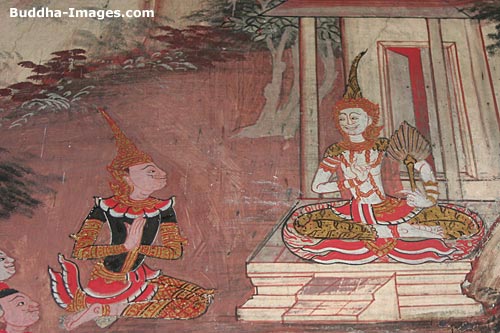

When Temiya (not shown in picture) was six years old, they set an elephant upon him, but Temiya unharmed and unmoved. | | When he was five, they tried to terrify him into speaking. He was placed in the center of a house thatched with palm leaves. A servant was then ordered to set fire to it. Where normal children would have run away shrieking, the Bodhisatta remained motionless and sat quietly as the fire came closer to him, until he was taken away by his attendants. At six, they let an elephant loose at him ; at seven, they allowed serpents to coil about him. Still he remained unharmed and unmoved. In the following years, they showed him terrifying mimes, threatened him with swords, and made holes in four sides of a curtain around his bed and had conch players blast their sound through to him. They tried him with drums and sudden bright lamps in the middle of the night, but they failed to break his trance. Desperate, they covered him with molasses and allowed flies to cover and bite him, but he did not flinch. They forced him to remain unbathed, but his need for cleanliness did not overpower him. Pans of fire were placed under his bed, causing boils to break out on his body, but still he said to himself that hell was a hundred thousand times worse. His parents besought him to speak, to move, to listen, but he dared not.

At sixteen, when he would have been named heir apparent, they led him to a fumed chamber and tried to tempt him with beautiful maidens, but he stopped himself from breathing in order not to be weakened by the fragrances.

At last, the king summoned the soothsayers and asked them why at his son's birth they had not mentioned any threatening signs of this affliction. Not understanding Temiya's behavior but unwilling to admit their ignorance, they explained that they had not dared cast a shadow on the king's joy when, after so many years, he had been given a son. But now, fearing for the safety of the country should an apparent idiot be named heir to the throne, they predicted dangers to the king's life if Temiya were allowed to remain in the kingdom. Alerted by their words, the king asked what he should do. They advised him in this way: 'You must yoke some horses to a chariot, send your son away in it, passing by the western gate, to a graveyard, and there he must be buried.' When the queen heard of this plot, she knew the time had come to make the request which the king had promised years ago to grant. 'Give the kingdom to my son', she demanded. 'For once he is crowned, he will certainly speak.' The king protested. 'Impossible, my Queen, for your son brings ill luck to us.' Then give it to him for seven years', she responded. Again the king refused. 'Then for seven months', she pleaded. 'O Queen', he said, 'I dare not.' "Then, alas, for seven days," she sighed. "Very well." The king relented. "Your wish is granted." And so it happened that Temiya was given the kingdom for seven days. He was led around the city, sometimes on an elephant, sometimes on men's shoulders. Still he would not move either his limbs or his lips. On the seventh day, his mother begged him to speak, for on the day he was condemned to die. The Bodhisatta gravely considered her request, thinking to himself: "If I do not break my silence, my mother's own heart will break ; if I do, I shall have wasted in one second what efforts I have made for sixteen years. Moreover, if I keep my pledge, my parents and I shall be saved from hell."

Thus, Temiya again decided to be patient. For the day was near when he would be freed from the fear of inheriting the throne, and on that day, he would be able to speak. As the next morning dawned, the king gave his final orders to Sunanda the charioteer. "Yoke some horses to a chariot and set the prince in it. Take him out the western gate and find ground in which to dig a grave. After you have dug the hole, throw him into it and break his head with the back of your spade to kill him. Then scatter dust over him and make a heap of earth above. After bathing yourself, come back here."

Sunanda took Temiya off, but though he thought he was passing through the western gate, the Death Gate, he did in fact drive to the eastern gate, which was the Victory Gate, and one of the chariot's wheels struck the threshold. At the sound, the Bodhisatta knew he was on the threshold of attaining his freedom. By the power of the gods, a graveyard appeared. Sunanda stopped and removed Temiya's royal ornaments from him, releasing him in one stroke from his yoke of royalty.

The Bodhisatta was at last freed from his vow, and as Sunanda worked at digging the grave, Temiya thought to himself, "In sixteen years, I have never moved my hands or feet. Can I do so now?" Whereupon he rose, rubbed his hands together, rubbed his feet with his hands, and alighted onto the ground, which at his touch became like a cushion filled with air. He then exercised his limbs by walking back and forth until he was satisfied that he had the strength he thought he had lost.  | | The Temiya Jataka -

Temiya confirms his strenght by lifting a chariot. | | This was his only chance to escape kingship and enter the forest as an ascetic, and the Bodhisatta wondered, was he powerful enough to overcome Sunanda if he tried to prevent his escape? As a final test of his strength, the Bodhisatta seized the back of the chariot and lifted it high with one hand as if it were a toy cart. Indeed, his power was confirmed. He walked over to the charioteer and tried to jolt him into looking at him with these words : "Behold the man you seek to kill, not deaf nor dumb nor lame. Stop or bear the wrath of hell, for by this act you'll die."

Sunanda looked up but was so dazzled by the Bodhisatta's beauty that he did not recognize him at first. Again Temiya identified himself. Suddenly Sunanda understood and fell at his feet, stammering that he would be honored to escort the prince home to inherit the kingdom. He who was destined for Buddhahood chided him, for nothing would deter him now from leading the pure meditative life. He described his previous existence and subsequent generations in hell and then ordered Sunanda to return to the palace immediately to tell his parents that he was still alive and thus spare them unnecessary grief over the loss of their only son.

As the charioteer approached the palace alone, the queen, who had been waiting by a window, saw him, assumed that her son was dead, and began to weep. But when Sunanda told her his story, she ceased. The king was told what his son had done, and he and the queen set out at once for the Victory Gate, hoping to lure the prince home.  | | Temiya has become an ascetic and lives in the forest. He preaches to his father, the King, who kneels before him. | | When the long procession of horse-drawn carriages came to a halt, the royal pair found their son living in a hut of leaves prepared for him by Sakka. They saw that he had already put on an ascetic's garments of red bark and leopard skin, a black antelope skin over one shoulder and a carrying pole over the other. His hair was tied up and matted, and he held a walking staff in one hand. Temiya welcomed them and explained to them the reasons for his sixteen years of self-denial. In awe of their son, they no longer begged him to wear the crown but were themselves inspired to embrace the holy life. Returning to the palace, the king ordered the royal treasure jars to be opened and the gold to be scattered about like sand. Sakka built for the entire kingdom a hermitage three leagues long, so that all who aspired to Nirvana could partake of the meditative life. |