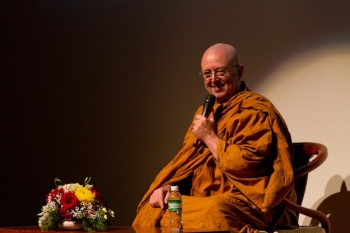

A Forest Monk - An Interview with Ajahn Brahmavamso

This interview is an excerpt from: A Forest Monk and a Zen Roshi

Radio National (ABC) – The Spirit of Things, with Dr. Rachael Kohn

< Part 2 of 2 >

Dr. Rachael Kohn: It's all about freedom, isn't it, about our perspective on freedom, what constitutes freedom. I mean when I think about what constitutes freedom for me, its spontaneity, its learning, its choice. What is it for you?

Ajahn Brahmavamso: Well there are two types of freedom. The freedom of desire and the freedom from desire, and most people in the world only know the freedom of desire, the freedom of choice. In Buddhism, especially in meditation, we're looking at the freedom from choice, the freedom from desire.

So one is so content, so at peace, that desires don't come up. One is free from the tyranny of these desires always pushing or pulling you, and telling you what to do. And it's… those are the orders which are coming from inside of each one of us, ordering us to be somehow different, ordering the pain to go away, ordering us to achieve some sort of goal, which we don't really know why we're reaching for this, but we're supposed to do it. So these are the orders, which in meditation we're becoming free of.

RK: Did you always know why you were reaching for this goal to be a Buddhist monk, to be an abbot?

AB: No, an abbot just happened by bad luck, but being a Buddhist monk, I'd always had an inclination, that even though you saw many, many people who had so many things, that they did seem to have the opportunity to live their dreams, their dreams never stopped, they were never free from this, always reaching out, this stretching, this hunger, this thirst, and that hunger, that thirst, like any hungry person or thirsty person, is not all that comfortable. Sometimes we want to end thirst, we want to end hunger and be satisfied forever, but that never seemed to happen. But when I came across some Buddhist monks, they were the happiest people I'd ever seen.

They appeared to be free, and even though that many wealthy people, successful people in the world, they are looked upon as being icons, looked upon as being people we try and emulate. If you actually asked them, or interview them and ask the question 'Do you really feel free?' then I think they would give some very interesting answers. But if you ask a monk who lives in a monastery with many rules, and many things you can't do, if you ask a monk 'Do you feel free?' actually the feeling is freedom. So the ideas of freedom, the freedom of desire and the freedom from desire, in our modern world, we've got so much liberty to follow our desires and actually achieve those desires, basically we can do almost anything we want. But how many people feel free?

RK: It all depends on what we expect from life. I know that your message is often about happiness, and how the point of life is kind of like that song, 'Don't Worry, Be Happy', which is all about changing one's attitude, not really about changing the world. And yet you would know that that kind of an attitude can also be breeding a certain indifference to the world.

AB: OK, well I don't think this relates to indifference at all, because many people change their attitude and the world changes with it.

Now the attitude of anger, of trying to get rid of problems, is like the attitude to the pest exterminator, and the attitude of the pest exterminator is instead of trying to live with nature, he always wanted control and eliminate all those things which create problem for us, and that could be a husband or a wife or it could be sort of some enemy which we perceive as being our pest. And you find you can't eliminate all the pests in the world, nor can you eliminate the pests in your own body, like cancers and other sicknesses. Nor can you eliminate the pests in the world. Some time there comes a time to learn how to live at peace and in harmony with nature.

RK: Does Buddhism ever teach a resistance to things which are dangerous, which are bad, which are evil?

AB: Yes, we teach a resistance to anger, we teach a resistance to jealousies, we teach a resistance to stupidity. Those are the things, which we should really be resisting, you know, the anger and the feelings of revenge, the hurt, the grief, the guilt inside of us, all those negative emotions, which make our world. Those are the things, which we want to resist, to understand, to overcome, by letting go. And so those things aren't there any more.

RK: I like the story that you tell about the lecturer who comes into the classroom and brings a jar full of rocks. Can you tell that story?

AB: OK, yes, that's actually from the internet, so many of your listeners will probably know that one, but it's a good story. There was a lecturer at a university who was showing just how broad his wisdom was, and instead of reading out his lecture notes one morning, he came with a big jar and put it on his desk. And while everybody in his class was wondering what he was up to, he started to put in some stones from a bag, one by one, into the jar until he could get no more in. And once he could get no more stones into his jar, he asked his class 'Is the jar full?' and the class said, 'Yes, it is.'

He smiled, and from under the desk he got out another bag, and that bag was full of gravel, small stones and one by one he managed to fit those small stones in the spaces between the big rocks. And once he could get no more small stones in, he looked up at his class and asked 'Is the jar full?' Now they all shook their heads and said, 'No'. They were on to him by now. And so he smiled and got another bag, of sand. He poured that sand on top of the big rocks and small rocks, shook the jar, much of the sand went into the spaces between the big rocks and small rocks. After he could get no more sand in, he asked once more, 'Is the jar full?' And again the class said 'No'. And he got some water and poured that in. And after he could get no more water in, he stopped; he asked the class, 'What am I trying to prove? What is the purpose of this demonstration?'

Now this was a business school, so one of the students in the class put up their hand and said, 'Sir, it shows to us that no matter how busy our schedule, we can always fit something more in.' And he said, 'No, no, no, that's not what I'm trying to show. What I'm trying to show is if you want to fit the big rocks in, you have to fit them in first. Don't leave them to the last, otherwise you will never get them in.' It was a story about priorities, what you should really fit in to your schedule of your day, of your life first of all.

So there are some things which many people realize are the precious stones, the big rocks of their life, like their family, like their relationships, like their peace of mind, whatever it is, and sometimes we leave them till last in our day, in our week, in our life, we find we never have the opportunity to fit them in. And that's one of the reasons why people don't find happiness. Their priorities are not correct. We should always remember that story of the stones in the jar, and put into our life what's very, very important first of all. The other things you can always fit in, but later.

RK: Ajahn Brahm, are there any more things that you want to fit into your jar?

AB: Fit into the jar? Just peace and happiness for myself and for others. I mean after all, that's what's most important to me in my life, is the happiness of myself and the happiness of others, but what I found after many years of life as a monk, I cannot distinguish between the happiness of others and the happiness of myself. So that's why I go out and serve as much as possible, to give talks, to tell stupid stories to make them laugh.

RK: You're very good at it.

AB: Thanks very much.

RK: We’re sitting in front of what looks to be a fairly traditional altar I suppose, with the great Golden Buddha in the center, and lots of lotus flowers around. Can you explain the symbolism of this?

AB: Yes certainly. I mean we have at the very top there, a golden Buddha sitting in meditation with a bit of a smile on his face, and obviously that's a symbol of peace, and when people see images like that, it's meant to engender a very soft and gentle feeling inside of them of peace. We have the candles on the sides of the Buddha, that's always been like the symbol of wisdom, because you have to light a candle to dispel the darkness, and for a long time that has been a symbol of enlightenment, so the wisdom is there, no-one owns wisdom, but we need to have a candle in order to actually see it for ourselves.

We have also on our shrine here, the lotus. The lotus is also a very potent symbol of Buddhism. Some of the lotuses we have there are ornamental, with many, many leaves on them, many petals, which is a symbol of the thousand petalled lotus, which is one of my favorite symbols for meditation, because to open the petals of a lotus, it means that the sun has to maintain its warmth on the thousandth petal before that opens up to reveal the 999th petal, and the sun has to stay on that thousand petal lotus a long time before it starts to open up the innermost petals.

The innermost petals of a lotus are the most fragrant, the most subtle and the most beautiful, and if you're lucky, and the sun maintains its warmth long enough, then the heart of the lotus can really open up and you can see what is called the jewel in the heart of the lotus. That is the very old mantra in Tibetan Buddhism, om mani padme hum, ‘Hail to the jewel in the heart of the lotus’. It's a symbol for meditation because you have to have mindfulness, unremitting, without any interference or stopping for a long time, to open up this thousand petalled lotus of your mind and to see what's truly inside, the jewel in the heart of you.

Rachael Kohn: Ajahn Brahm thank you so much for being on The Spirit of Things.

Ajahn Brahmavamso: No trouble, thank you.

To read Part 1 of 2: http://mingkok.buddhistdoor.com/en/news/d/24478