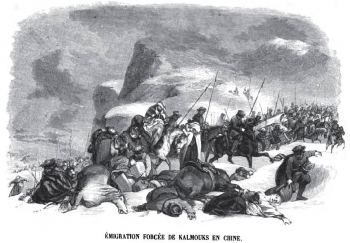

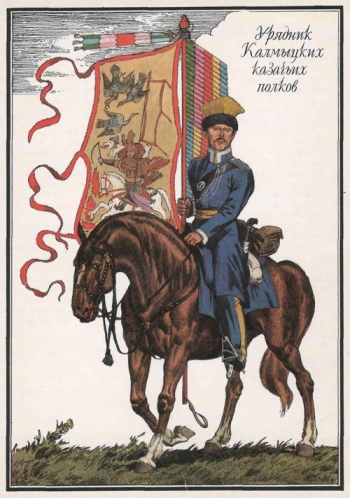

In Kalmykia, located far closer to the center of Russia than Buryatia, the tsarist government took a much more active role in trying to prevent the spread and growth of Buddhism. At the end of the eighteenth century, after the independent Kalmyk khanate was swallowed up and the out-migration of most Kalmyks to Dzungaria, the Kalmyk steppe was transformed into one of the administrative regions of Russia. It was placed under the authority of the military governor of Astrakhan, and its Buddhist church was also completely subjected to government control. The church's head, the Shadzhin-Lama, or Lama of the Kalmyk people, received his salary from the Russian government.

The tsarist administration attempted to restrict the spread of Buddhism through its Regulation on the Administration of the Kalmyk People of 1838, which limited the number of clergy to 2,650 in 76 khuruls at a time when the real number of clergy was 5,270 and the real number of khuruls was 105. Nine years later the Regulation of 1847 reduced the legal limits to 1,656 clergy and 67 khuruls. Nevertheless, the first choira – a school for education of Kalmyk clergy – was opened in 1907, and in 1908 the second such school was opened. After 1910 the Baksha-Lama of the Don Kalmyks, Mynko Barmanzhinov, opened a third choira. Thus the position of the Buddhist church was well established right up to the time of the Revolution.

In 1914 another Buddhist people joined Russia. The Tuvans were the only Turkish people who confessed Buddhism, and they became subjects of the tsar when Russia annexed Tuva and made it a protectorate named Uriankhai, after the fall of the Manchurian dynasty in China. At the time of annexation there were already 22 Buddhist monasteries (khure) and about 4,000 lamas and khuvaraki in the Uriankhai province. About half of the lamas lived not in monasteries but as householders with families.

Sedentary Buddhist monasteries began to be built in Tuva in the 1770s. The greatest of these at the turn of the century were Erzinsk (founded 1772), Samgaltaisk (1770), Oiunnarsk (1773), Upper-Chadan, and Lower-Chadan (1873). The Buddhist clergy of Tuva was led by the head of the Chadan khure, who carried the title Kamba-Lama and was himself subject to the Buddhist church of Mongolia. Many khure had schools in which children were given an elementary religious education. Tuvans usually sought higher theological education in Mongolia.

By the beginning of the 20th century Russia was interested in strengthening its ties in the East, and it especially wanted to establish direct contact with the theocratic governments of Mongolia and Tibet. To this end, a Buddhist temple was built in Saint Petersburg. The construction and operation of this temple was overseen by Agwan Dorzhiev (1853-1938), the outstanding Buryat lama who was nominated as a debate-partner to a young 13th Dalai Lama, gained his confidence and acted as representative of Tibet in Russia. Working closely with him was D.D. Itigelov (1853-1924), who occupied the post of Bandido Khambo Lama from 1911 through 1918. Itigelov's body was exhumed in 2002 in accordance with his will and found to be incorrupt, which was considered by local Buddhists to be evidence that he had attained the highest level of holiness.