A So-called Artist: An Interview with Helen Mirra

By Harsha Menon

Buddhistdoor Global

| 2019-06-27 | Through the activities of an uncomplicated form of weaving and solo daylong walking, Helen Mirra—who goes by the moniker “hm”—is engaged in the overlapping realms of ecology, conceptual experimentation, and somatic experience. While resisting the limits of a fixed identity, foundational Buddhist ideas concerning ethics and insight shape her subtle art practice. For instance, hm’s 2003 exhibition 65 Instants was part of the national consortium Awake: Art, Buddhism, and the Dimensions of Consciousness, while her 2014 survey book Edge Habitat Materials includes a chapter of Nagarjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakārikā, and she has made a succession of participatory city walks devoted to the cultivation of equanimity, supported by institutions including the Aspen Art Museum, the Havana Bienal, and the High Line in New York City.

hm previously taught in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University, and with the Committees of Visual Art and Cinema & Media Studies at the University of Chicago. The exhibition No Horizon: Helen Mirra and Sean Thackrey is on view this summer (2 July–25 August) at Berkeley Art Museum.

hm. Photo by Stefan Romer

hm. Photo by Stefan RomerBDG: In the early 1950s, Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki introduced intellectuals in New York City to Zen Buddhism through his lectures at Columbia University. You have a strong affinity with the American composer John Cage, who was present at those talks and whose practice was shaped by that engagement. How you did you first encounter Zen Buddhism?

hm: I grew up in Rochester New York—not close, not far, from New York City. Before I was born, my mother had been introduced to Zen practice by Audrey Fernandez, who was one of the founders of the Rochester Zen Center and had invited Philip Kapleau to teach there. Audrey was the indisputable sage/saint figure of my childhood, totally down to earth and totally mysterious, so kind and so careful. At her house I would tarry around Kapleau. So I didn’t ever really feel like I was introduced to Zen, nor did I take it for granted. When I was a kid I had the idea to move to NYC in order to study mycology at the New School for Social Research with Cage, but by the time I was ready to go he was no longer teaching the course.

BDG: Do you tend to identify as having a Buddhist practice and an art practice as separate, or perhaps as one activity that is expression of a life force?

hm: I recognize that I appear to be a so-called Buddhist and a so-called artist. I have formally received the bodhisattva precepts. I sit in a zendo most mornings these days and I am responsible for the arising of constructed objects that are shown in exhibitions. And while I don’t want to resist the terms, the shared modifier is key for me as a reminder of the limitations and presumptions that all categorizations perpetuate.

I consider walking and weaving to be essential Buddha activities. What I mean is, they are prehistoric, they are in the direction of the primordial. They are not dependent on skill or imagination. And though I experience them as complementary interdependent activities, I also distinguish between them.

BDG: You recently celebrated “nine years of slope-walking” with an exhibition in Mexico and a book publication. I know this walking practice originated in an artist residency in Europe where you weren’t provided with a studio, so you decided to take the residency outside. How did that open up your practice and what do you do exactly?

hm: Walking had been a conceptual subject for me for about 10 years prior, and it was a decade before my body synced up. I went to Basel in 2008 with the presumption that I’d be spending the year making sculpture in the studio, because that is what I had been doing for a while, and also with great doubt about continuing “as an artist.” Not so well aligned! The lack of a studio was the perfect condition for the crisis which had been rumbling to really show up. I might say I was wholehearted about my practice, but not wholly incorporated with it. Not that I could see it that way at the time. So I took to the mountains and they took me. And at the end of the year I knew I wanted to keep walking, and that if I could do that as a so-called artist, then I was all in.

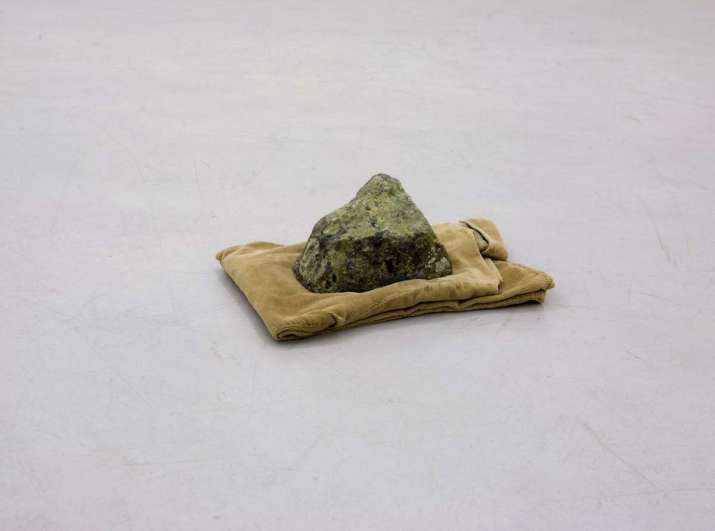

March–April, 2018. Image courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake

BDG: Also, there are times when you invite others to join you in the walking, adding a participatory element reminiscent of Thich Nhat Hanh. How did inviting others to join you in places such as the New York High Line feel? What did this add to your experience of walking by yourself?

hm: For a number of years, walking (apparently) alone in the forest/hills/mountains, and then coming home to the city (when living in Cambridge, MA), I was aware that I was always waiting, in a way, to leave again. And that this was a problem, that I was not present in the city. Then I started practicing half-smiling, exactly as described by Thich Nhat Hanh: meeting absolutely everything and everybody, always, with equanimity and friendliness. And my relationship to the city flipped over. Around this time a curator asked me if I’d “do” a walk for a group exhibition because he had an understandable misunderstanding that the walking I’m engaged in is performative—which it isn’t. The coincidence allowed me to see that there was this unadorned and accessible structure that I could offer to others, this synthesis of half-smiling and walking.

That said, when I’ve invited others for a walking, it isn’t with me per se. Rather, we meet at a designated place, and I share some ideas about both half-smiling and walking, and then we set off in different directions—walking separately in space, together in time—and then meet again to share lunch at a vegan restaurant. And lunch is free of cost for the participants, reversing the common cultural-capitalist formula. While I’m emphatic that these walkings are not artworks, they have been organized under the auspices of various exhibitions, and I appreciate that they are ambiguous in this way—it fits in neatly with the understatedness of the activity.

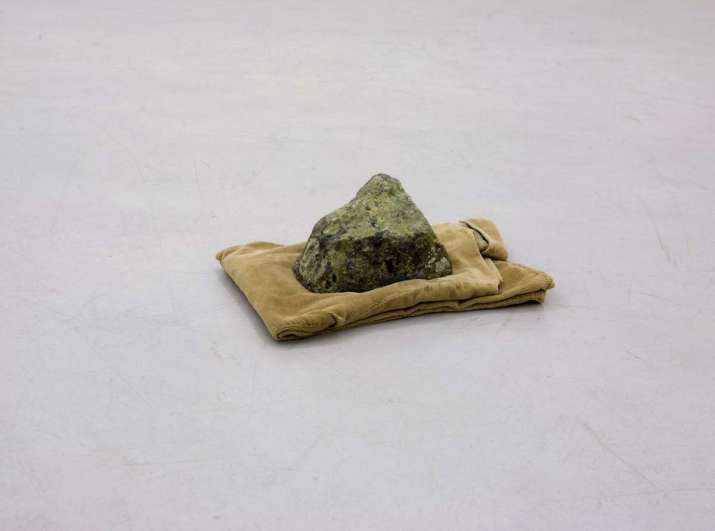

Mantle, 2007. Image courtesy of Galerie Nordenhake

Mantle, 2007. Image courtesy of Galerie NordenhakeBDG: Sound also plays a significant role in your work, both in playing instruments and recording. Were you originally a musician? What kind of training did you have?

hm: Hmm . . . I have no formal training. Maybe my first guide was a Thelonious Monk vinyl record that I chose to borrow from the library when I was 11 or 12, because of the photograph of him on the cover—I think it somehow registered that he was foremost a listener, and that this is what a great musician is. Maybe I could feel, even though I didn’t know it at the time, that he was taking away notes [from chords] rather than playing them straight or augmenting them. Also especially formative were American Folkways LPs. Same thing probably—evidences of unpretentious and humble dedication without fixation. These days I play an echo harp, also known as a tremolo harmonica, not to make music per se; just as an amplifier of breathing.

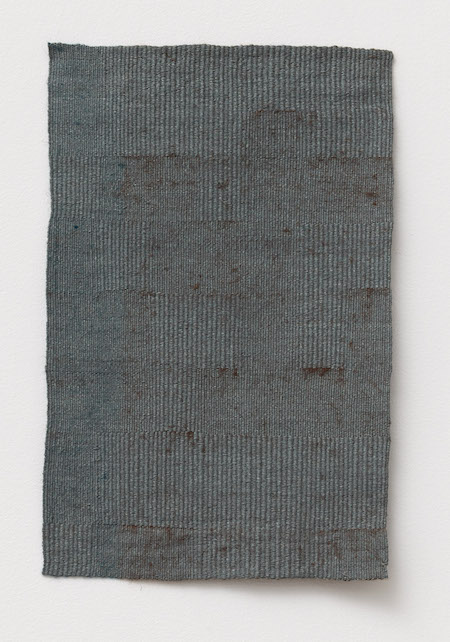

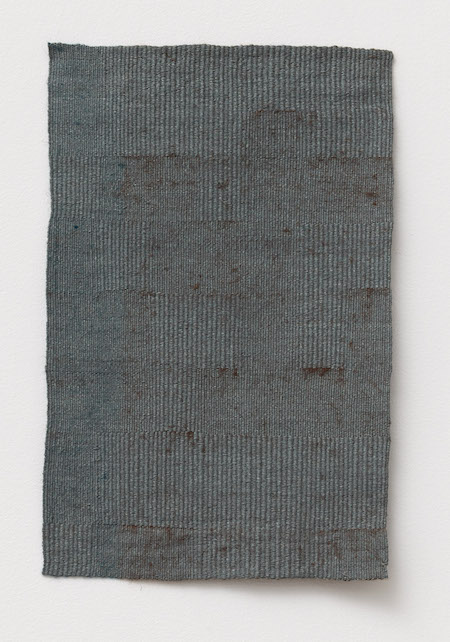

BDG: What part do textiles play in your work? Do you situate yourself in the continuum of artists who weave and do you see a gendering to that aspect? I am thinking of Annie Albers, of course, and others. Or for you does the weaving resonate as more gender neutral?

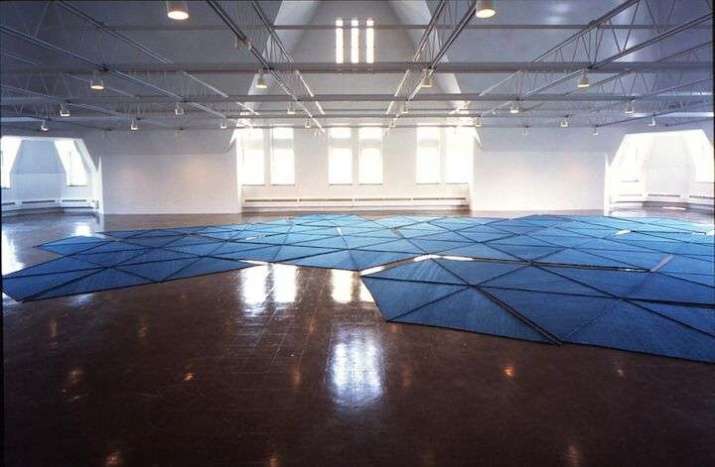

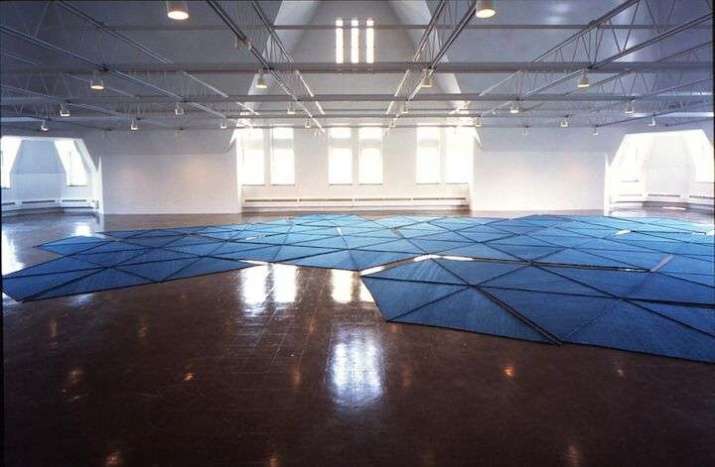

hm: I find it moving that textiles precede texts by thousands of years. And though I love Anni Albers, she was more of an inventor and I’m more of an anti-inventor, if anything. My relationship with weaving is not gendered; the myth of Penelope doesn’t resonate with me. For example, living in Kerala, South India in 2000–01, my main occupation was figuring out the math and constructing a rather large floor sculpture titled Sky-wreck, which is alternately a scale model of a piece of the sky that has fallen or a patch for a hole in the sky, with the presumption that the sky is a geodesic dome. It is made of indigo-dyed cotton, and the material was produced by a collective in Auroville, in Tamil Nadu, where the small group of weavers were all men.

Some of the Zen ancestors recognized weaving as relevant. In the Mountains and Rivers Sutra, Dogen writes of the horizontal and vertical, which I read as a description of the simultaneity of relative and absolute reality of the fundamental sublime. Hongzhi had been a bit more romantic about it, describing brocade, gold, and jade. If I had the opportunity to offer a verse responding to his verse for the first case in the Book of Equanimity, it would be: Often walking, loom and shuttle.

Detail of Sky-wreck, 2001. Photo by Tom Van Eynde

Detail of Sky-wreck, 2001. Photo by Tom Van EyndeBDG: What are you currently working on and where do you see your practice heading?

hm: Can’t resist the reply: toward death and hopefully the deathless. I am moving in what would be measured as smaller circles, while they feel more infinite. I am often walking forward and sometimes stepping, literally, backward, and recently have been thinking about figuratively moving to the side (no doubt that bright idea found me through weaving.) I’m increasingly inclined not to travel by air. I’m committed to being in the world, not as an explorer or a researcher but as a witness, especially listening to the non-dominant, non-humans.

And I am at the very beginning of what could be a 2–3 year project, which is to weave through all the “leftover” fiber that I have in my studio, which is mostly mill-spun linen, following the chance-based parameters that have seemed appropriate to work with since I moved back to California in 2016. The sequence is ordered according to the color spectrum—who am I to know better than a rainbow about how to proceed?

BDG: Is there anything else you would like to add?

hm: As always, I’d like to add nothing, yet I seem to be adding something. Thank you very much.

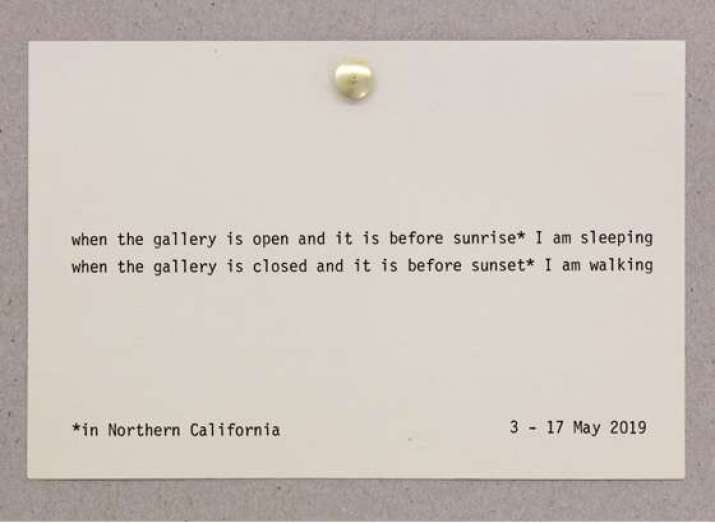

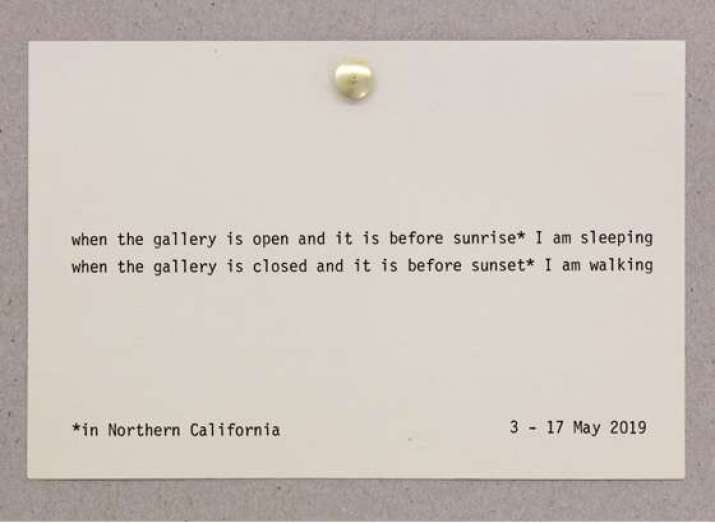

Notice for freundlich Nein / friendly No. Image courtesy of Meyer Riegger Galerie

Notice for freundlich Nein / friendly No. Image courtesy of Meyer Riegger Galerie