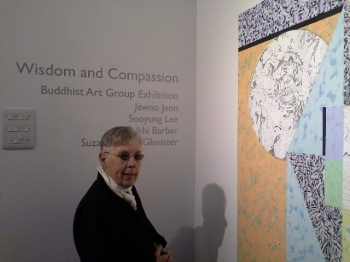

Raymond Lam reviews Mokspace’s “Wisdom and Compassion” Buddhist Group Art Exhibition

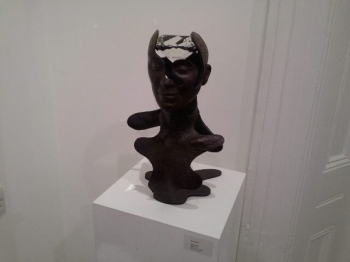

Across from the venerable British Museum (which itself houses a vast collection of Buddhist sculptures, frescoes, and other articles of immeasurable historical and spiritual value) rests a cozy but sharp and spacious gallery called Mokspace. Specializing in Korean art and art informed by Korean aesthetics, the gallery’s new curator, May Kim, has been hard at work putting together a Buddhist-themed exhibition titled “Wisdom and Compassion”. It runs from the 14th of May till the 9th of June. The curator has told me she would very much like to hold an even better exhibition in the future, but hosting Buddhist art in private galleries on London's streets is in itself a welcome trend. May's work will hopefully balance the public's awareness of current art against the indulgent Sotheby's auctions or the obvious ostentation of Christie's purchases. The exhibit’s original lineup consisted of five artists, but without Daniel Berlin, the remaining four showcasing their masterpieces were Jewoo Jeon, Sooyung Lee, Sukhi Barber, and Suzanne Rees Glanister (who has written a piece about her work and inspiration elsewhere on this publication). It would have been easy albeit somewhat lazy to conclude that contemporary Buddhist art is simply “Buddhist art” that has been updated with modern techniques like abstract or digital drawing. Mokspace’s exhibit is nothing short of revolutionary. It is revolutionary because the visions of the concerned artists are radical. Consider this image: when traditional Buddhist art is subverted, one can only dissolve into emptiness and allow completely new visions of the Buddhist teachings to manifest. In the case of Sukhi Barber’s sculptures, these new visions also dissolve into emptiness quite literally as part of her work. Visually, vacant space constitutes the meditator’s bronze cast and frame, and the ingenious manipulation of the meditator’s very body allows Barber to craft meaning and morality from the space within and without. Hence the apt names: “Radiance” is a burst of light from within, the “Appearance/Emptiness” statues feature a swirling, coherent unity of matter and the nothing in between it, and “Crystal Clear” is literally a diamond within a surreal bust’s emptied head.

Jewoo Jeon’s photography, in contrast, takes advantage not of emptiness, but of darkness and shade. Emptiness does not shape or give birth to form here, but darkness clashes with light to reveal ancient monoliths of liberation. The Buddhas in his pictures are made visible by light, but critically, they are given shape by darkness. Without the differentiation of shadows, where could the distinction, folds, or highlights be contrasted? Just as the human world holds a balance between hope and misery optimal enough for spiritual practice and therefore a Buddha’s appearance, Jeon’s Buddhas and arahats peek out from their darkness, but they cannot leave their shadows lest you lose them and your best chances for liberation. Suzanne’s art, its manifold colors framed against Mokspace's white, immaculate walls, is inspired by stories. She has told me that much of her favorite pieces were motivated by the Lotus Sutra, but stories are not always religious, nor do they always fit neatly into a spiritual narrative. Of course, I cannot claim to have interpreted all her artwork with certainty. What religious art can do is to address these realities within a compassionate framework, and Suzanne's is an onslaught of dizzyingly complex, messy patterns and figures - all with their own tragedies, comedies, and triumphs within shapes of simple, stark geometry as basic and real as the Four Noble Truths.

Coincidentally, I have just finished editing a book review from the author of Buddhistdoor’s In My Image: The Missing Buddha in Buddhist Art series, Jeffrey Martin. He concludes his feature on Sangharakshita’s The Religion of Art with the remarks: “Even a casual reading of the texts may lead one to question whether consuming art is an abuse of the senses.” Martin goes on to note that the dilemma of enjoying art is a recurring question in English-language internet Buddhist forums. To be fair, this question is not simply a cogitation dreamed up out of boredom by the chattering middle classes, but of real, significant importance to modern Buddhists living in a media-ruled society. “Perhaps more of them, caught between aestheticism and asceticism, will someday soon be exploring further the potential of art in Buddhist ethics,” writes Martin.