FEATURES|THEMES|Philosophy and Buddhist Studies

Approaching Chan, Part 1

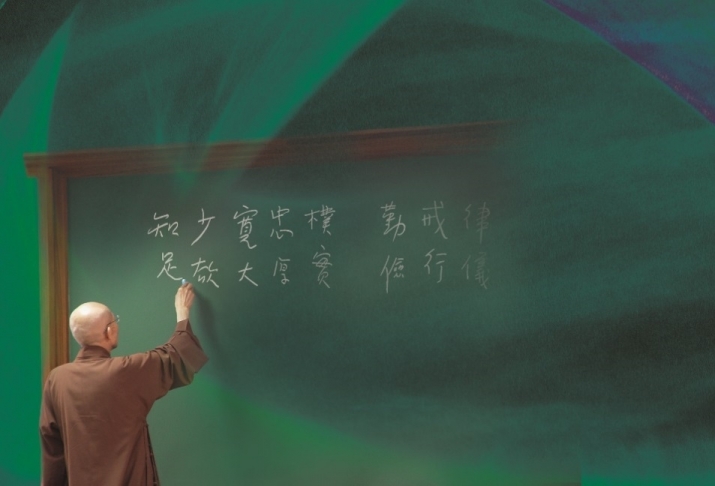

The Late Chan Master Sheng Yen placed a great emphasis on sangha education. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural Center

The Late Chan Master Sheng Yen placed a great emphasis on sangha education. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural CenterThis article is the first in a series of three that seeks to explain some of the subtleties of Chan Buddhism for newcomers to the school.

“A defining feature of Chinese Buddhism is the integration of the fundamental Buddhist principles found in India with Chinese Confucian ethics and the Daoist’s pursuit of naturalness and spontaneity. In this process of amalgamation, earlier precepts were recalibrated to become “Rules of Purity,” tailored to the ethical traditions of the Chinese people, while Indian contemplative practices were replaced by an emphasis on rediscovering one’s inner wisdom, to attract those drawn to the Daoist pursuit of naturalness and spontaneity. As a result, Chinese Buddhism has remained free from the confinement of formal precepts and avoided the pitfalls of romanticized, laissez-faire approaches to Buddhism. While being free from the burden of tradition and leading a lifestyle that is spontaneous and at ease, Chan practitioners nevertheless emphasize and exercise vigor and pure conduct in their daily practice, which is precisely the original intent of Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings.” (Master Sheng Yen 1980, 5)

After Buddhism was brought to China from India, the initial focus on sutra translation gradually evolved into the eight Chinese schools of Mahayana Buddhism: the Three Treatise (Sanlun), Pure Land, Tian Tai, Consciousness-Only (also known as Yogachara), Huayan, Vinaya, Chan, and the Tantric schools. The late Chan Master Sheng Yen (1930–2009) compared the approaches of the eight schools to modern fields of study, stating: “The approach of the Consciousness-Only school resembles that of science, and the Three Treatise school is akin to philosophy. The approaches of the Huayan and Tian Tai schools parallel literature. The mantra school (Shingon shū) and Pure Land can be considered forms of aesthetics. Meanwhile, Chan embodies the core teachings of the Buddhadharma. Master Taixu [1890–1947] also said, ‘The crux of Chinese Buddhism is Chan,’ where the teaching of any of the other schools can be reduced to the spirit of Chan. As for the disciplines (Vinaya) school, it is the foundation of Buddhism.” (Master Sheng Yen 2007, 128)

Recognizing precepts as the foundation of Buddhist practice, the implementation of Chan in daily life adheres to the spirit of the Buddhist precepts, while also taking into consideration contemporary laws and ethical standards. In Master Sheng Yen’s view, “The precepts are guidelines for Chan practitioners to lead an ethical life, which can be distilled to the following: One should do whatever is needed, refrain from doing what is not needed, and never commit what is prohibited.” (Master Sheng Yen 1999, 288) Chan Master Baizhang Huaihai (720–814), the fourth-generation heir of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng (638–713), established “The Rules of Purity for Monasteries,” which were drawn up in a way that did not confine them with the specificity of the precepts observed in Theravada Buddhism and some Mahayana schools, while still adhering to their overarching principles. Furthermore, the customs of Chinese society and the characteristics of the broader temporal and geographic contexts were considered in creating these guidelines for Chan monastic life. “The objective of setting up such guidelines is for Chan practitioners to live in a way that is content, free of desires, and to encourage the practitioners to follow dhūta [Sanskrit; work intended for spiritual progress] practices and the practices of humbleness and repentance. Consequently, the attitude derived from living this way will be settled and stable, harmonious and engaged. This is also the reason why the Chan monastic lifestyle remains to this day simple, neat and organized, grounded and tranquil.” (Master Sheng Yen 1999, 289)

The sangha represents purity of body, speech, and mind through the diligent observation of the precepts. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural Center

The sangha represents purity of body, speech, and mind through the diligent observation of the precepts. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural CenterGenerally speaking, all Buddhist practices are based on precepts, meditative concentration, and wisdom. By observing the Five Precepts*, a Chan practitioner can better achieve concentration and uncover the true wisdom that lies within everyone. Observing the precepts can prevent the conditions for vexation from arising, while practicing meditative concentration helps to subdue the impact of vexation, yet only the cultivation of wisdom can remove vexation.

This is why Chan emphasizes the cultivation of wisdom through practice in everyday life; daily life is Chan. The Sixth Patriarch Huineng said, “Walking, standing, sitting, and laying down—in one pure direct mind, and the unmoved practice ground (direct mind) is the real Pure Land.” His disciple, Master Yongjia (665–713) likewise said, “Walking is Chan. Sitting is Chan. In speech, silence, movement, stillness—the essence of mind is always at ease and tranquil.” This is the reason why many Chan masters attained enlightenment while performing daily chores. One famous example is Master Baizhang’s disciple, Xiangyan Zhixian (812–898), who was an expert in sutras and shastras, but could not attain enlightenment. He decided to leave his monastery to tend the fields daily and investigate hua tou, a form of meditation common to Chan. One day, as he was working in the field, Xiangyan picked up and tossed aside a piece of broken brick, which hit a bamboo stalk and with a sharp “crack!” The very instant that he heard the sound, Xiangyen attained enlightenment. This story exemplifies a typical way Chan was practiced after the time of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng, when Chan teaching in China had fully evolved into a kind of direct, "sudden" method.

However, this direct method of practice can sometimes be overly abstract and difficult to grasp for beginners, therefore traditional Chan training nowadays begins with sitting meditation (Skt. samadhi). The cultivation of samadhi is taught through sitting in the correct posture and using methods to regulate the body, the breath, and the mind, to enable practitioners to begin to settle and stabilize their minds. Only then can they begin working on uncovering wisdom. In other words, by first following a concrete and clear methodology, new practitioners are able to gather and unify their scattered minds. Then they can begin to uncover their intrinsic wisdom, which is the attainment of so-called “enlightenment” or “seeing one’s true nature.”

This mode of Chan practice is suitable for the majority of people. Historically, in the beginning stages of Chan instruction in China, this kind of gradual and sequential method has been frequently adopted. Upholding the precepts leads to the development of samadhi, which itself leads to the uncovering of wisdom. Tiantai Master Zhiyi’s (538–97) book, Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (小止観) mentions that Chan practitioners must first complete the 25 prerequisite practices before they can really begin the practice of śamatha-vipaśyanā.

Master Sheng Yen guiding practitioners during a Chan retreat. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural Center

Master Sheng Yen guiding practitioners during a Chan retreat. Image courtesy of Dharma Drum Cultural CenterAt Dharma Drum Mountain, Master Sheng Yen developed a set of standard guidelines and classes to help beginners learn basic meditation, starting from adopting the correct sitting posture, which is then combined with Eight-form Moving Meditation, relaxation exercises, and standing and sitting yoga, to help practitioners regulate their bodies and breathing. Counting breaths, slow walking meditation, and fast walking meditation are taught in conjunction to further help practitioners regulate and focus their minds, before more advanced methods are presented.

* The Five Precepts: 1. To refrain from taking life; 2. To refrain from stealing; 3. To refrain from sexual misconduct; 4. To refrain from lying; 5. To refrain from using intoxicants.

Approaching Chan, Part 3: The Methods of Lingji’s Huatou and Caodong’s Silent Illumination (Buddhistdoor Global)