FEATURES|COLUMNS|Silk Alchemy

Beyond Gender: Seeking the Sublime in Sacred Art

An ”icon . . . is beyond art. It is a real presence that we venerate. A still, almost silent presence looking tenderly at us, helping us to pray and lifting our minds and hearts above this Earth . . . to heaven, our true homeland”*

According to recent neuroimaging research, the veneration of spiritual imagery triggers hyperactivity in a part of the brain called the caudate nucleus, a key structure in the neural pleasure/bliss zone. As I have discussed in earlier essays on imagery and the brain, symbols and color can essentially rewire our neural biology and have profound effects on our well-being. They can also direct our thinking, due in part to the feelings of awe and rapture that the veneration of sacred art can induce. But if meditation on sacred imagery can affect the individual so profoundly, what are the implications at the societal level?

I am increasingly intrigued by the use of religious and spiritual iconography throughout human history. Perhaps more controversially, I am also curious about the unarguable patriarchal paradigm in which much of this sacred art was created and our continued attachment to it today. Moreover, what does the contemporary upsurge in subjective sacred feminine artwork mean for tomorrow?

Of course, given the non-dual nature of ultimate reality, gender shouldn’t really be part of the conversation. But in this phenomenal existence, gender attribution and apparent hierarchy profoundly affect our relationships and social climate. This is a vast and ongoing conversation that I can only skim the surface of here, so in this essay I will only touch upon some of the early influences on and of figurative iconography as a prelude to a broader dialogue.

Art is an extraordinarily effective propaganda tool that has been used for centuries to create what anthropologist Clifford Geertz called cultural “moods.” That is to say, so much of how we view and feel about our culture, good and bad, has been reflected, shaped, even directed visually. It is fascinating to question how much of our “mood” has been determined by imagery at the behest of determining factors other than the artist’s personal intuition. Intuition is neurologically attributed to right-brained activity rather than the analytical left, and is typically associated with the feminine more than the masculine. Yet while women have long been the subject of much religious art, they have simultaneously been blocked from active participation in its creation.

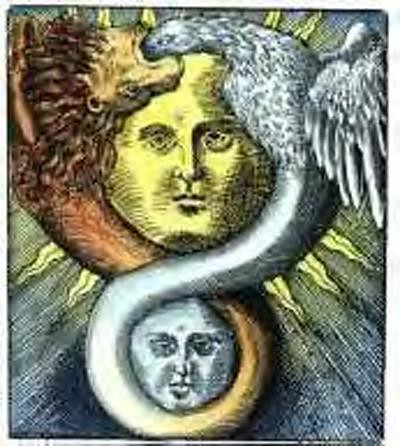

Beyond our immediate earthly surroundings, one of the first significant influences of divinity that humans looked to was the sky, and the Sun was regarded as most fundamental to life on Earth. Before the ancient Egyptian sun god Ra, the earliest known solar deities in Egypt were seven sun goddesses—Wadjet, Sekhmet, Hathor, Nut, Bast, Bat, and Menhit. Meanwhile, the Moon, Khons, was depicted as masculine. Many other cultures have correspondingly depicted the Sun as feminine and the moon as masculine. As noted in translated texts by Tuvan shamans, we can even see this in very early spiritual art.

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo, from the Sistine Chapel, features very interesting “freehand” embedded symbolism

The Creation of Adam by Michelangelo, from the Sistine Chapel, features very interesting “freehand” embedded symbolism“The Sun resembles the ovum, the Moon resembles the sperm. Modern observations support assigning the Sun to the feminine and the Moon to the masculine. Under the microscope the non-mobile ovum (propelled through the fallopian tubes but not by its own motion) looks like a sun with its many rays of living protoplasm emanating from its spherical surface. The motile sperm reflects the swift motion of the Moon as it propels itself in successive crescent-shaped waves. Also, under the microscope, the ovum appears more red and the sperm more white, confirming the old traditions of tantric Hinduism as these are the two colors of the solar Kali and the lunar Shiva. They are also the colors of their pair of yogic channels pingala and ida, not to mention the pair of red and white tinctures in the central doctrine of the transformation of the soul in alchemy.”**

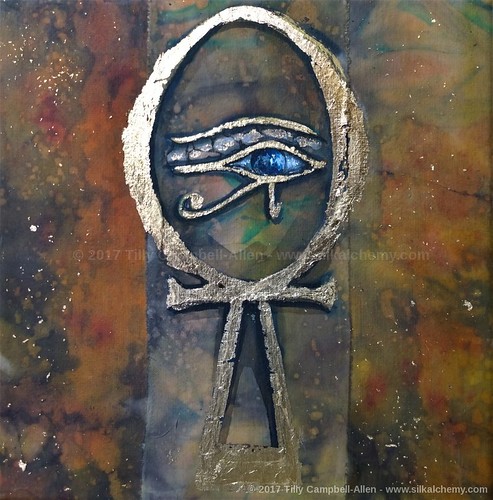

Alchemy, too, has its roots in ancient Egypt. While societies around the world each realized gender roles in their own way, typically the women’s primary drive was as the mother and caregiver, with men providing from outside the home. This played out in ways that either supported women or rendered them subordinate to the influence of testosterone. The practice of “Kemeticism,” conversely, (Kemet being the name of ancient Egypt and their spiritual practice) seemed to celebrate gender equality. In fact, one ancient symbol still familiar to us today was so venerated that evidence of its usage was found in Mesopotamia and Persia, and among the Minoans. The ankh, one of the most ancient ideographs, seems to have represented “eternal life” through the perfect unification of male and female.*** A strong argument for subsequent Christian iconography and its societal implications was that the Christians of ancient Alexandria, known as the Copts, adopted the ankh in their practice but soon excised the feminine aspect (the upper loop) completely. Once the emperor Constantine had replaced it with the Roman sword, the Crucifix as we recognize it today was born. By now a new iconography was setting the cultural “mood:” the sun was deemed masculine and the feminine aspect was downgraded.

The attribution of gender to celestial bodies is significant and there is clear evidence that many societies experienced a similar cultural switch from the life-giving solar goddess to an omnipotent male sun god. The moon became identified as the reflective, emotional feminine, most notable in astrology, which had a marked influence around the world as a rigorous study of the heavens was underway in Alexandria. It is said that the destruction of the great library of Alexandria set progress and learning back more than 1,000 years. However, some of the knowledge and thought produced there had already made its way to Greece, heavily influencing Grecian philosophy and Hermetic alchemy, now with this strong patriarchal bias.

The ensuing Hellenistic influence on Buddhist art in India became evident, and non-figurative symbols representing enlightenment were replaced by large images of Siddhartha Gautama as the Buddha and heavily influenced figurative imagery. The yang of Oriental balance was the fiery Sun and the yin the watery Moon. It is interesting to reflect on how women were/are expected to play out this energy as the traditional yin to the masculine yang, and this is systematically expressed in religious art. Yet it might also be argued that pushing out new life is the most yang thing that can be done, and women are often considered “fiery” when fully expressing their power. We do see some of this yang power in Buddhist deities such as Vajrayogini and the raw creative/destructive energy of Kali, both of whom can appear somewhat terrifying. But deities and archetypes generally adhered to certain cultural “moods,” with a patriarchal bias. And when the art is venerated as sacred, the imagery activates the caudate nucleus, giving us profound feelings of rapture and union with the divine that becomes heralded as “truth.”****

A vast proportion of iconographic religious art was created within masculine paradigms. Accordingly, being born masculine was considered a privileged step closer to enlightenment, with women typically viewed as unworthy of creating religious imagery. However, might it also be possible that in the realm of sacred art, women are less likely to conform to dogmatic “rules” in preference to following their intuition? Regardless, in a patriarchal paradigm, the almighty creator was male. In the West, male artists expressed some of the most spectacular venerations of the religious experience at the behest of the 15th century banking dynasty, the House of Medici. Artworks that came to speak to generations as reflections of the Christian Divine were arguably less a subjective experience and more what the financial backers deemed acceptable.

In the East, even the Great Goddess of Hinduism, Mahadevi, is overshadowed by male counterparts such as Brahman. In Buddhist art, with so much training in precise proportions and symbolic postures, who were the artists laying down these insights and rules? Even in Vajrayana artwork, for example, (probably the most gender-equal Buddhist culture we can look to) the ultimate inseparability of compassion and wisdom, or form and emptiness, is typically represented in such a way that the central fully faced figure is usually male with his smaller contorted female consort often positioned with her back towards us and a look of veneration toward her larger partner. Subtle as it seems, there appears nonetheless, a visual gender hierarchy.

The artists within a given paradigm are hugely influential in reflecting and setting the “mood” of a society. From the late 1960s, we started to see a surge in a new type of art inspired by subjective spiritual experience—visionary, shamanic art representing the divine feminine in all her multifaceted glory, ignoring formalism, yet profoundly respectful of the spirituality. I find this very interesting, not least as it is one of the most spontaneous subjects in my own artwork. I also feel it is extremely important with—I hope—significant implications for the cultural “mood” of tomorrow.

Was the first depiction of the Buddha’s face some 300–400 years

after his passing, based on images of the Greek deity Apollo?

While the rules of sacred geometry and specific proportions may continue to be embedded in the faces and postures of deities in Buddhist art, what if it is time to recall a primal wisdom, to be open to evolving some of those masculine “rules” by creating new intuited feminine “moods” that are more appropriate to these unbalanced, turbulent times? Rules and moods that are no longer determined by a single gender and inevitably represent stereotypes within an established hierarchy, but instead elevate both the feminine and masculine side by side; no one bigger or smaller, and no contortion. We can leave celestial energies untainted by gender hierarchies and bear witness to the return of the loop to the cross, the return of the ankh.

Sacred women painted by women.

According to Alain de Botton, Marcel Proust saw “art as a mechanism that can restore beauty and interest to things that have been unfairly neglected.”*****

Proust observed: “The great quality of true art is that it rediscovers, grasps, and reveals to us that reality far from where we live, from which we get farther and farther away as the conventional knowledge we substitute for it becomes thicker and more impermeable.”

I think he had a point . . .

* English composer Sir John Tavener (1944–2013), as quoted in lecturer Emma Clark’s talk at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts “What is Sacred Art and Why is it Important Today?”

** Why the Sun is Feminine and the Moon Masculine (Lionpath)

*** According to both followers of Kemeticism and as brought to the West by British surgeon and researcher into myth and symbols Thomas Inman (1820–76) in the paper Ancient Pagan and Modern Christian Symbolism, first published in 1869 and again in 1875.

***** Alain de Botton, Art as Therapy.

Footnote on other forms of sacred art: Traditional works in many other cultures however (Celtic, Scandinavian, Aboriginal, Native American, etc.) focused less on a masculine paradigm and more on reflections of their reality, dreamtime, totems, magic, decoration, etc. Often these were profoundly spiritual. These traditions seemed to express a very different relationship between genders. Of course, beyond gender reference is the art of sacred geometry found throughout the world. Be it intricately woven to form the complex visual feast of Islamic art and architecture; profound meditation yantras in tantric Hinduism, embedded into Buddhist thangkas, through to carvings like the flower of life embedded in the stonework of ancient Egypt.