Image courtesy of Shambhala Publications

I said, “Inside there’s a yes and a no.”

He said, “Follow the yes.” (5)

This exchange between Zen master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi (1904–71) and student David Chadwick offers a glimpse of the treasures that feature in Shambhala’s recent publication Zen Is Right Now: More Teaching Stories and Anecdotes of Shunryu Suzuki (Shambhala 2021). Originally from Texas, Chadwick formally began training under Suzuki in 1966 and was ordained as a priest in 1971. Chadwick is best known for his endeavors to preserve the teachings and life of Suzuki Roshi, and he previously wrote two books about the late Zen master: Crooked Cucumber (Broadway Books 1999), a biography of Suzuki, and Zen Is Right Here (Broadway Books 2001), which showcased teachings by Suzuki along with anecdotes from his students. Chadwick’s most recent work, Zen Is Right Now, continues along this vein, offering readers a fresh and exciting collection of vignettes to explore.

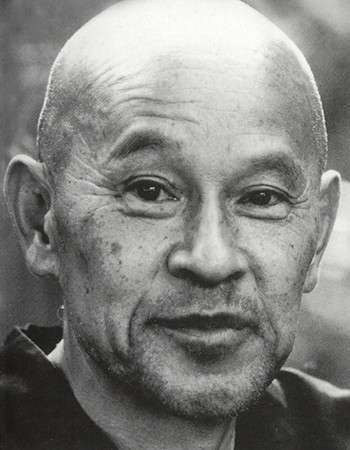

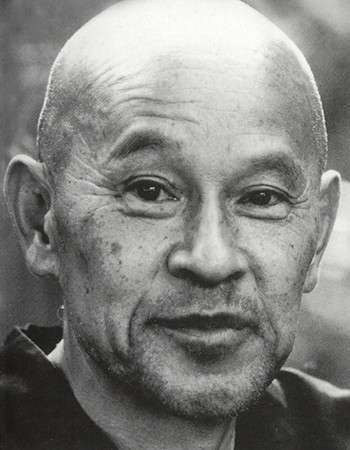

Nicknamed “crooked cucumber” by his teacher Gyokujun So-on Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi is renowned for being one of the founding figures of American Zen Buddhism. While his nickname points to his unpredictable and forgetful character, Suzuki’s legacy for Buddhism in the US is not to be underestimated. Born in Kanazawa Prefecture, Japan, Suzuki was ordained as a novice monk at the age of 13 and received Dharma transmission in the Soto Zen lineage at the age of 22. He lived in his home country until 1959, when he accepted a position as a priest in the United States. The author of many publications, including the popular Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (Weatherhill 1970), Suzuki founded the first-ever Zen center outside of Asia, Tassajara Zen Mountain Center. He also founded the San Fransisco Zen Center, which to this day remains one of the most influential Zen organizations in the US.

Although Suzuki’s original mission in the US was a humble one, his ambitions were not. As highlighted by Chadwick: “[Suzuki] came to minister to a congregation of Japanese Americans at a temple on Bush Street in Japantown called Sokoji, Soto Zen Mission. His mission, however, was more than what his hosts had in mind for him. He brought his dream of introducing to the West the practice of the wisdom and enlightenment of the Buddha, as he had learned it from his teachers.” (xiii)

David Chadwick. Image courtesy of Shambhala Publications

David Chadwick. Image courtesy of Shambhala PublicationsZen is Right Now is comprised of an introduction by Chadwick, quotations from Suzuki’s students, and a compilation of teachings and anecdotes. It also features a list of reading materials for those who would like to learn more about Suzuki and his legacy. According to Chadwick, the majority of the stories in the book are rooted in a particular setting: “Many of the vignettes herein are from exchanges that happened at Tassajara Zen Mountain Center during shosan, a formal question-and-answer ceremony with Suzuki. In interviews, emails, and conversations, Suzuki’s students have related shosan memories . . . more than from any other single source.” (ix)

The insights provided by Suzuki’s students are heartfelt and a delight to read. As former student Seiyo Tsuji recalls: “He repeatedly told me that what we’ve got to do is to establish an American Zen. He’s Japanese, and so am I, but he wanted to establish an American Zen, whatever that turned out to be.” (xii) Another student reflects on her former teacher’s laid-back attitude: “Suzuki had a very human style. He never put on airs. He was traditional yet able to take a chance, which he sure did in San Francisco in the sixties—going there and starting Tassajara and all. I’ve never met anyone like Suzuki since.” (x)

Shunryu Suzuki. Image courtesy of Shambhala Publications

Shunryu Suzuki. Image courtesy of Shambhala PublicationsIn true Zen fashion, the anecdotes and teachings that feature in the book tend to be brief yet profound. While it is a relatively short read, I enjoyed taking my time and letting the words on each page really sink into my consciousness and permeate the rest of my day. Proceeding in this deliberate manner enhanced my practice. While Suzuki’s teachings struck me as unique on the one hand, it was also a pleasure to discover in his words many of the qualities that are now key characteristics of American Zen Buddhism.

For example, there is a focus on the Zen master and the Zen practitioner as being human and flawed, as depicted in the following vignette:

A student said to Suzuki, “I feel pretty foolish. How do you feel?”

Suzuki replied, “Ah. Yeah, I feel the same way.” (62)

And the Zen master’s eccentricity and playful disobedience:

Once at the Oakland Museum, Suzuki Roshi was admiring a densho, a hanging bell used in Zen temples. He asked a guard if he could hit it to see what it sounded like but, after some further inquiry, was told he could not. Later, on his way out, he bumped into the bell, as if by accident, and was quite pleased with the sound it made. (103)

And finally, the diligence of attending to what comes up in practice, moment by moment:

A student said to Suzuki that she kept trying and trying but just couldn’t get anywhere in her zazen, that her legs hurt all the time and she couldn’t stop thinking.

“That is our practice,” Suzuki said. “Our way is to sit with painful legs and wandering mind.” (29)

According to Chadwick, instead of being preoccupied with enlightenment, Suzuki was much more concerned with “sharing in the joy of practice.” (12) The ways in which his teachings are presented here are a wonderful reflection of this because the reader gains insight not only into Suzuki, but into an entire community of people who share in the delights and struggles of their practice. The result is charming, if a little confusing at times. While I was not always sure who to attribute a saying to—the lines can be a little blurred in this regard—it seemed to me that this was beside the point. After all, it is not about rigidly following a particular doctrine, what matters is that we are on this path together and that we have the ability to inform one another in our desire to live life to its fullest potential.

As Chadwick puts it:

Suzuki encouraged his students above all to be themselves and not to use him or Buddhist teaching as a crutch. He said in a lecture, “Your conduct should not be based on just verbal teaching. Your inmost nature will tell you. That is true teaching. What I say is not true teaching. I just give you the hint.” He’d say he had no particular teaching. To me, he was just always trying to help us wake up. (xv)

References

Chadwick, David. 2021. Zen Is Right Now: More Teaching Stories and Anecdotes of Shunryu Suzuki. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications.

See more

Cuke.com

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Liu Yingzhao and Buddhist Alchemy: A Silicon Valley Executive Talks Spirituality and Integration

Buddhistdoor View—Re-examining the Relationship Between Celebrities and Buddhism

Practicing Perfection in Art, Buddhism, and Life

Curiosity and Doubt: The Spiritual Career of Judith Simmer-Brown

Buddhism and Basketball: Phil Jackson and His Zen Coaching

More from Coastline Meditations by Nina Müller