A long time ago, monks in India debated about the importance of “study” and “practice,” trying to sort out whether their loyalties lay as “monks of the scriptures” or as “monks of meditation.” The common idea of “theory versus practice” – or philosophizing as opposed to religious action – was already the subject of many debates before the modern era. But I think this idea is a false dichotomy. A false dichotomy is a situation where only two choices are considered when there are actually other options. The dilemma of “study versus practice” conjures up an image of having to choose between being:

1. Stuck in one’s study reading all day, or:

2. Staying in the forest away from all friends and family and meditating for hours on end.

It is true that study might not lead to practice (the fact that someone is a scholar of Buddhism does not mean he is a scholar who believes in Buddhism), but it certainly provides a more solid foundation for practice – and perhaps a more intellectually honest way of spiritual life.

I am probably biased since my loyalty is offered to my temple even as I enthuse about and participate in the university environment. But I do not think that one can escape the fact that the Buddhist religion (at its best) is a heavily intellectual tradition. Unlike many other religions, we even have our own system of philosophical logic, kicked off by the early Abhidharmists and refined by titans like Nagarjuna, Dignaga, Dharmakirti, and many more. Buddhism’s complexity and depth have sometimes been criticized as a weakness rather than a boon, which I think is rather strange – why should we settle with intellectual mediocrity? Isn’t a more scholarly and in-depth religion the better one? And the fact that its philosophy is complex in no way denies that one cannot make a leap of faith. The following example may illustrate why I think so.

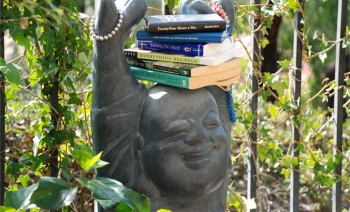

Today, the context of study versus practice has expanded to include laypeople who are either believers or studying Buddhism in an academic context. Some time ago in Spring 2006, Charles Prebish wrote an article called “The New Panditas” in the magazine Buddhadharma, which notes how many academics rooted in the American school of Buddhist Studies are part of a younger and growing generation of “scholar-practitioners.” These are theologians, historians, linguists, Buddhologists, logicians, and grammarians who are believers engaged in the critical study and scholarship of their religion. Due to various cultural and sociological reasons, the presence of the scholar-practitioner is felt strongly within the American school of Buddhology and more pronounced than that of the Anglo-German school. Prebish himself is aware of the possible stigma that can arise in the academy if a teacher declares his spiritual loyalty to his own subject of study. Yet, the fact that the American school now matches older traditions in terms of scholarly output and cutting-edge research means that there may be something to be said for this figure of the scholar-practitioner. They were able, in other words, to overcome the stereotype that one’s spiritual practice is compromised if she is buried in books (what’s so bad about being buried in books anyway?), or that one’s intellectual rigour is lessened if she decides to worship the Buddha.

Buddhist Studies is no longer the sole domain of non-Buddhist researchers cloistered in the ivory towers of old universities (which was admittedly the case at the turn of the 20th century).

The motto of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London is the famous adage, “Knowledge is power.” In the not-so-good-old days of British colonialism, knowledge provided a specific type of power. To know the languages, cultures, and politics of other regions in the world was to be empowered to manipulate and subjugate them (with the obligatory gunpowder) to British rule. Nowadays “power” simply carries a less sinister tone, which is the ability to make informed, critical decisions and evaluations about the complex cultures and religions of one’s focus or interest. In my opinion, it is not helpful to see the systematic study of the Buddhist tradition as somehow fundamentally opposed to the expression of Buddhist belief and discipleship. The practitioner-scholars of the United States have demonstrated that a modernist unity of theory and praxis is very much possible. Why not be a bookworm and a retreat junkie at the same time?