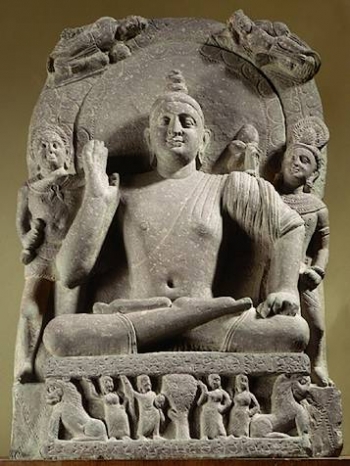

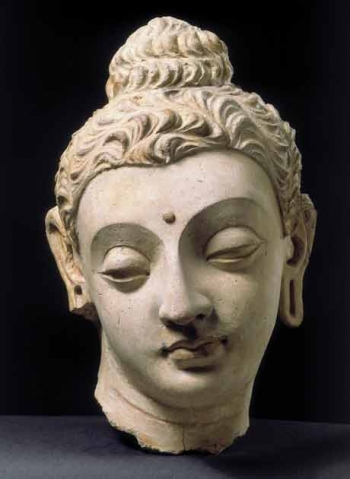

It is high time we brought back the lost traditions of the Mathur?n and Gandh?ran art schools. Mathur? and Gandh?ra were two regions in ancient India that played host to two distinctive styles of Buddhist art. Mathur? exhibited an extremely lively aesthetic and was influenced heavily by South Asian mythology. Gandh?ran art was a fusion of Indian and Hellenistic themes, and it is common to see Greek forms like Heracles and biographical subjects (such as the Buddha’s birth, first sermon, death, etc.). Both schools didn’t care about showing how the Buddha might have actually looked when he was alive. The artisans at Mathur? drew from traditional Indian mythologies about the “superman” (mah?puru?a) whilst the Hellenistic sculptors at Gandh?ra draped the Buddha in a toga and gave him the air of a Greek philosopher or Roman emperor. “Pax Buddhica,” so it would seem!

Buddhist art as it survives today is immensely diverse. Unfortunately, throughout the course of the religion’s long history many things have been lost, and without a doubt Buddhism’s weakened grip over the Indic heartland and the oasis kingdoms of Central Asia were great setbacks. Art was one of the victims, for the two great schools died out and no longer exist as a living stream of creativity. Of course, the sculptures, friezes, and archaeology remain, but this is different to having breathing people who sculpt these masterpieces for a living. Much scholarship in Buddhist Studies examines these things from the past. They are dead things. I am posing the suggestion that they can be living once more. Why shouldn’t they be?

Of course, if we ever see these sculptures being crafted for contemporary Buddhists, they can never be the same as the original. Like the reconstructionist religions of Asatru (modern

day belief in the Norse gods) or Kemetism (contemporary worship of the Egyptian deities), “modern-day” Mathur?n and Gandh?ran art can never be what they originally were. When a tradition suffers a break in continuity (whether due to decline or external forces), it can never return to its geographical and temporal context even if it is revived for future generations. We cannot truly resurrect Mathur?n and Gandh?ran art. We can only introduce new, living schools of religious sculpture that replicate their material, style and themes. If statues similar to the Brussels Buddha (this is a Gandh?ran Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas) are produced for contemporary Buddhists or art collectors, they are most likely not going to be made at Gandh?ra (which is in modern day north Pakistan and east Afghanistan), but in the West, perhaps in one of the great Buddhological centres of Brussels, Leipzig, Göttingen, Paris, or London. It will be produced under strict quality control, with the input of German or Franco-Belgian scholars in art history or Hellenistic and Indian sculpture. Obviously this won’t be Gandh?ran in the historical sense at all!

I, for one, am cautiously optimistic. I can’t see any factor that would decisively deny or render impossible a new campaign to reintroduce Mathur?n and Gandh?ran art to the public. There is the question of demand, of course: will anyone care? Will anyone want to purchase these works? I think Gandh?ran art has particular potential since our Western Buddhist communities are growing in the Anglosphere. In China our Buddhas look Chinese, and in Thailand they look Thai. Why should the West not get its Caucasian Buddhas, complete with their Mediterranean and Persian drapery? I, for one, would like to see more moustached Maitreyas and Bodhisattvas. More importantly, why should the West overlook its Hellenistic heritage in South Asia? For a time, especially during the Ku???a Imperium, there was a proud tradition of Western expatriates (especially in Bactria) producing Greco-Roman sculptures for wealthy Indian monks and their monasteries. There’s much ado about Greco-Roman statues and busts, so let’s see some in Western Buddhist monasteries! The latter have every right to have the former, since the Greeks, thanks to Alexander, were part of the Buddhist heritage even before the Common Era.

In one of his books, contemporary philosopher A.C. Grayling of Birkbeck College related a story about how archaeologists discovered the body of a baby immersed in an amphora filled with honey. She died prematurely and probably tragically, but the archaeologists could still use the honey on their morning toast because it was still sweet after 2000 years. Two great art schools that served the glory of the Buddha’s message were also lost too soon. Even today, Buddhist art is underrated for the weak reason that not many know about the heritage of Mathur? and Gandh?ra. The doctrine of impermanence is not an excuse to let things fall apart or to forget about them.

After all, the honey’s sweetness stays forever.