FEATURES|COLUMNS|Exploring Chinese Buddhism

Buddhism and the Law of Attraction: Musings over a Father’s Writings to His Son in 1602

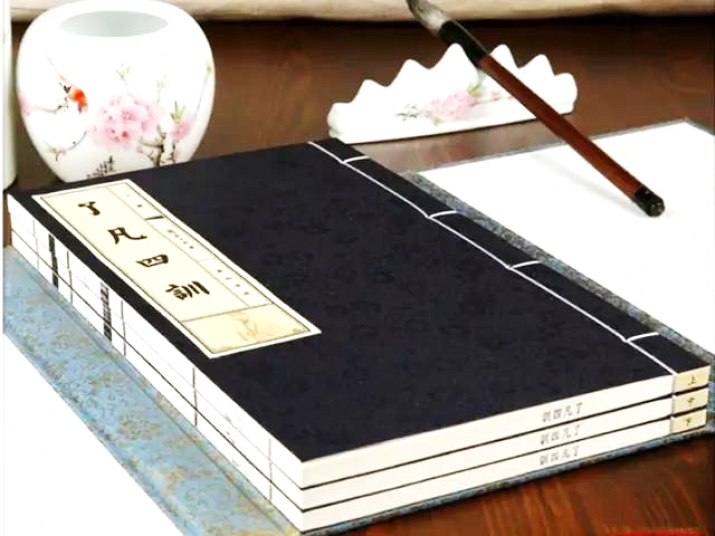

Liaofan's Four Lessons (了凡四訓). From sohu.com

Liaofan's Four Lessons (了凡四訓). From sohu.comIn the year of 1602, a father in China completed a text for his 16-year-old son. The father, Yuan Liaofan (袁了凡) (1533–1606), was a successful man. At a time when civil service examinations were the main means for commoners to be elevated to social elites, Yuan was one of the few who obtained jingshi, the highest degree in the examinations, among the candidates from all over the country, and at the end of his career he had risen to a position at the Ministry of War of the Ming court (1368–1644). However, his writings to his son were not about career advancement, marital happiness, or wealth procurement. Rather, they are about an ultimate question he had been pondering; whether one can create their own destiny.

His answer was yes. In his writings, composed out of four sections, Yuan Liaofan shared not only his own experiences with his son, but also the methods with which he believed one could change one’s destiny. The text was published later as Liaofan's Four Lessons (了凡四訓) and has motivated generations of Chinese up to this day. Since the text is largely inspired by Buddhist teachings, along with Confucian and Daoist thought, free copies of the book can be found at monasteries in China.

Such a book is relevant to all of us, as destiny, or fate, is a question that has baffled us mortals since the beginning of human civilization. In Chinese culture, we, on the one hand, have ancient sages who inspire people to realize their potential through self-cultivation and perseverance, while recognizing the order of society and the cosmos. But, on the other hand, we also have various ways of divination that use physiognomy, numerology, astrology, and I-Ching to predict one’s life path and fortune, that are widely practiced. Even in the history of western civilization, where individualism and free will is emphasized, the apprehension that one cannot escape fate still lingers: as predicted in a prophecy, Oedipus killed his father and married his mother; and the Almighty God already has a plan for each of us.

Yuan Liaofan struggled with destiny too, but in the end, he won. An elder foretold a series of life events for Yuan, including the exact rankings he achieved in civil exams and the exact years. However, he also predicted that Yuan would die at the age of 53 without a son as heir. Disheartened, Yuan simply let life run its course. Then he encountered a Chan Buddhist Master named Yungu, who showed him that both good fortune and bad fortune come from oneself. Following Master Yungu’s instructions, Yuan not only lived until the age of 73 and achieved a higher position in government than previously predicted, he also begot a son at age 53.

Yuan Liaofan receiving Venerable Yungu’s teachings. From a 2009 TV series on Liaofan

Yuan Liaofan receiving Venerable Yungu’s teachings. From a 2009 TV series on LiaofanTo a modern reader, Yuan’s story may sound like a textbook example of the Law of Attraction, a school of thought that gathered an immense international following after the turn of the 21st century. According to the Law of Attraction, one can achieve anything he or she desires with positive thinking. While this school of thought is eclectic in nature, drawing on ideas and quotes from faiths around the world, it often claims its origin back to the wisdom of the Buddha. However, how Buddhist is the Law of Attraction, when we compare it with Yuan’s writings?

To attract good fortune, advocates of the Law of Attraction espouse methods of visualization and affirmation. However, Yuan’s path to fulfillment, and the philosophy behind it, are completely different. Based on teachings of Buddhist masters, his own studies of ancient texts, and observation of real-life examples, Yuan listed three methods to change one’s destiny for the better: to rectify one’s mistakes and shortcomings, to do good things for others, and to stay humble. While the Law of Attraction encourages the use of vision boards to showcase one’s goals, Yuan kept an account of his merits and faults. He attributed his long life and the birth of his son to the merit he accumulated by doing three thousand good deeds with his wife, rather than mere optimism or strong longing.

For people who are looking for a magic wand to revive their life, Yuan’s methods may seem anticlimactic and even dubious. One may ask, how can I do things for others when I don’t even have enough time and energy for myself, and why do I have to do so much work? According to Buddhist principles of cause and effect, good gives rise to good, and an unsatisfactory outcome should be traced back to its problematic beginning. That was why, when Yuan complained about his fate, Master Yungu asked him, “why do you think you deserve a high position or a son?” Yuan reflected on this and realized that he had several weaknesses that would not make him a capable official or a good father. Therefore, he became determined to cultivate more virtues in himself.

Apart from improving his habits and personality, Yuan also made a conscious effort to conduct good deeds. The Buddhist Law states that, good or bad, your thoughts and deeds will eventually come back to you and to people who are close to you. That is how you create your own destiny. Then the question that follows is: how does one judge what is good and what is bad? An ethic debate on this matter can last for eternity, but Buddhism offers a lucid answer: to do things for others’ benefit is good, while to do things for one’s own benefit is bad. Yuan cited an allusion where Venerable Zhongfeng warned his lay disciples not to be deceived by appearance. Venerable Zhongfeng elaborated, “If you do things for others, even if you scold or hit others, it is good. If you do things for yourself, even if you say nice things and show respect, it is bad”. Thus, in his writings, Yuan encouraged his son to pursue a civil career not for fame, but to work for the benefit of others.

Buddhacarita, created by Billy Tan and One Academy for BBEP, 2014. Image courtesy of author

Buddhacarita, created by Billy Tan and One Academy for BBEP, 2014. Image courtesy of authorIn comparison, the Law of Attraction is concerned mainly with self-interest. The general audience has criticized it for its focus on material gains. From a Buddhist perspective, this approach is problematic, not because of the material gains, but because of the selfish motive behind it. In fact, such “positive thinking” or wishful thinking is nothing but desire, one of the causes of suffering in Buddhism. When you think about it, it is rather worrying to see how a school of thought, with the Buddha as a spokesman, promotes ideas that are against his teachings. Partial reading and misunderstanding of Buddha’s words are ubiquitous today. Many people around the world tend to assume that Buddhism teaches us that life is suffering and that all we can do is to accept it. Nevertheless, what Buddhism teaches us is to see clearly why life is suffering and how we can find happiness in this life and in the next.

Yuan Liaofan discovered the secret of life through Buddhism. Following the model of the Buddha, Yuan created his own destiny by making vows and by taking action to benefit others. In Buddhism, no one is undermined, as each of us has Buddha nature. Therefore, individualism in Buddhism eventually goes back to humanity. In the end, we are all equal and connected. Your achievement is my achievement. Your happiness is my happiness.