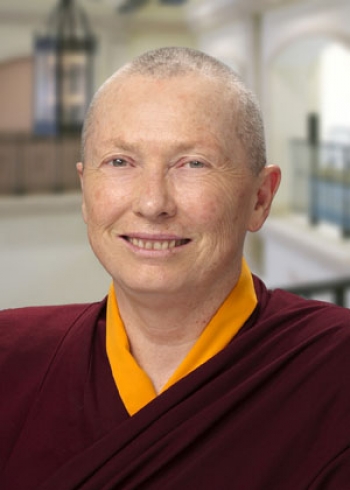

Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo is the Branch and Chapter Coordinator of Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women. In this series of seven questions we presented to her, she reflects on some key issues about Buddhist women and the long road ahead.

B: How is the future of women’s participation in Buddhism looking, judging from the results of this year’s conference? Certainly it varies region by region: which are the hotspots where development for Buddhist women is urgently needed?

KLT: The future prospects for Buddhist women’s development are excellent, if they get support during the crucial initial stages. Judging from this year’s conference, Buddhist women are becoming increasingly active working in their own localities and are linking up to support one another like never before. These international links provide vital inspiration, encouragement, and resources. The needs of Buddhist women in each country are different, however, which makes Sakyadhita all the more interesting.

While Buddhist women in Europe and North America are working on issues such as sexual harassment, greater representation in the U.N. and other international forums, historical research, textual analysis, including feminist analysis, and representations of women in Buddhist texts and institutions. Buddhist women in developing countries are vitally concerned with basic issues such as health, hygiene, access to Buddhist learning and practice, and training opportunities, including both monastic training and vocational training. In some areas, such as Buddhist psychology and meditation, they find common ground, which is very inspiring and empowering. Sakyadhita works to better understand the needs that Buddhist women are grappling with on the ground and to figure out ways to serve these diverse needs.

The international partnerships forged through Sakyadhita are extremely meaningful for women, many of whom have felt isolated, alienated, and discouraged. We want to address the most urgent needs first, such as the trafficking of Buddhist women and children, which are rife but often ignored, and healthcare, especially for women infected with HIV/Aids. At the same time, we realize that women need to follow their own dreams and passions, which may mean working on the basic issues of survival that are specific to their own communities.

Sakyadhita’s international conferences make women aware of new directions that need attention and methods that have proved successful in other countries. For example, women may begin to realize the lack of Buddhist education for children or the lack of prison Dharma projects in their own traditions or localities and become inspired by the work of other women to initiate them. By expanding their vision of what is possible, Buddhist women can determine their own priorities. The potential for Buddhist women’s social activism is immeasurable, limited only by a lack of qualified human resources and financial support.