FEATURES|VEHICLES|Mahayana

Buddhism in China: Crisis and Hope

The Donglin Buddha statue at Donglin Temple in Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province. At 48 meters high, this bronze statue of Amitabha Buddha is believed to be the tallest of its kind in the world. From en.people.cn

The Donglin Buddha statue at Donglin Temple in Jiujiang City, Jiangxi Province. At 48 meters high, this bronze statue of Amitabha Buddha is believed to be the tallest of its kind in the world. From en.people.cnSince its introduction into China two millennia ago, Buddhism has been accepted, digested, absorbed, and transformed to nourish the spirit of the nation, providing sustenance to the Chinese soul. Philosophy, religion, culture and the arts have all been deeply influenced by Buddhism, and it has had a profound impact on the worldview, outlook on life, and values of the Chinese people. Buddhism has become an inextricable part of China’s distinguished traditional culture, entwined with popular customs, lifestyles, and attitudes. Indeed, China has become a second homeland to Buddhism.

How can Chinese Buddhism survive and develop in the present era? This is an issue of concern not only to the Buddhist community, but to society at large. It has great significance for the preservation of our cultural roots, the promotion of national peace and happiness, and the development of social harmony and stability. It even affects our interaction with a multicultural world, for the purpose of coexisting peacefully and enjoying common prosperity.

This essay attempts to analyze the current status of Chinese Buddhism and assess its prospects—how it can avoid crisis and ignite hope. The author is acutely aware of this essay’s shortcomings and only wishes to initiate discussion.

1. The current crisis in Chinese Buddhism

In short, Chinese Buddhism is facing a crisis. Although there are many aspects to the crisis, this article will examine it from linear and vertical perspectives.

From a vertical, historical view, Buddhism flourished from the introduction of scriptures into China and their translation into Chinese, through a localization process and the establishment of eight major schools of Buddhism during the Sui and Tang dynasties. Shining brilliantly, it spread to Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia, and was uniquely influential in these regions. Then, like an arrow from a fully drawn bow, its momentum peaked and it went into decline during the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. Today it has plumbed a nadir, with few accomplishments in Dharma-explication, the nurture of talent, or expansion of the schools. The flames of enthusiasm from yesteryear have long since cooled. All that remains are a few flickering embers, buried deep within the ash heap of history.

From a horizontal perspective, modern transportation and communications, and especially the rise of the Internet, have accelerated the process of globalization. Even the vast Pacific Ocean has become a narrow ditch. As though through a magic lens, distant South America and Western Europe come into focus before us. All kinds of peoples, languages, religions, cultures, beliefs, and goods seem to have assembled in a single room before our very eyes. Chinese Buddhism was clearly unprepared for this new situation, and is at a loss over how to deal with it. It is as though many unfamiliar guests suddenly entered someone’s home. Not only does the host not know how to treat his guests, he even feels his own identity under threat and his maneuvering space reduced. This is the predicament confronting Chinese Buddhism.

Consider a revealing example. During China’s policy of reform and opening to the world over the last 30 years, the number of Christians in the country grew by several million. This should provoke Chinese Buddhists to reflect seriously: can we still say that Chinese people don’t need religion? Do Chinese people have no affection for the Buddha? Are the teachings of Christianity superior to those of Buddhism? How did the progress of 30 years come to exceed the advances over 2,000 years?

Clearly, Chinese Buddhism has been unable to keep pace with the times. After two millennia of immersion in a feudal agrarian system, it was abruptly dragged into the modern era and its complexities by three decades of reform and opening up. It can only look, astonished, at contemporary society, while the latter regards it as odd. So Buddhism and modern society are strangers to one another. They neither know each other, nor how to deal with each other. Some people even think of Buddhism as a cash cow, using religion to serve commercial ends. Repeated prohibitions of such activity have been ineffective.

If Chinese Buddhism doesn’t transform and rejuvenate itself according to the temper of the times, it faces a bleak future.

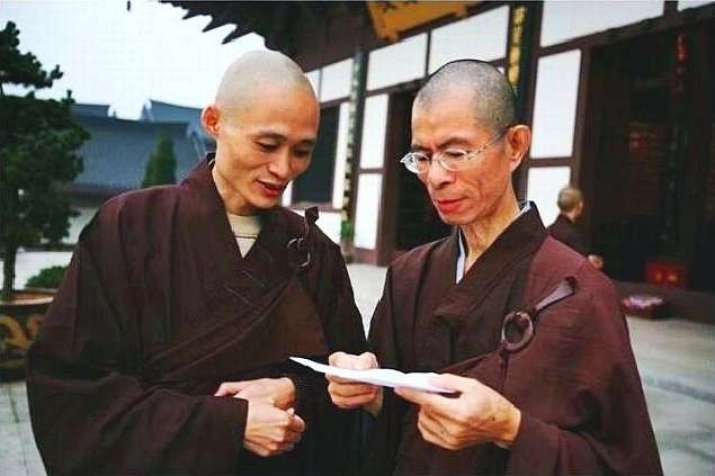

Master Jingzong, left, with Master Huijing. From wordpress.com

Master Jingzong, left, with Master Huijing. From wordpress.com2. Hopes for Chinese Buddhism

As long as the tinder isn’t exhausted, there are hopes of reigniting the fire.

Buddhism in China faces a severe crisis, but it still has a solid foundation built over 2,000 years. As long as we can identify the inheritance and recover the original inspiration, Chinese Buddhism can certainly flourish anew and illuminate the human world.

To be relevant, in both principle and practice, has always been the key to Buddhism’s survival and development. In terms of principle, the goal must be to achieve nirvana and Buddhahood. In terms of practice, Buddhism must suit the needs of the time, place, and people. And people must be able to practice it. In other words, Chinese Buddhism will only have a hopeful future if it can find a teaching and practice that will allow modern people to achieve Buddhahood in the contemporary environment.

With regards to principles, or teachings, the eight schools of Chinese Buddhism are equal. In terms of practice, however, people today live busy, fast-paced lives. They are full of worries and under heavy pressure. The Pure Land path fits the capabilities and circumstances of today’s practitioners, allowing them to “attain nirvana without eliminating afflictions,” as the saying goes. That is why we say the future of Chinese Buddhism lies with Pure Land. Indeed, the name Namo Amitabha Buddha is the undying spark of Buddhism.

There are five reasons for this:

i) Historical evolution

Buddhism’s evolution in China over two millennia can be summed up in the phrase, “With Chan as special characteristic, and Pure Land as summation.”

The establishment of the various schools in the Sui and Tang dynasties marked the completion of the Sinification of Buddhism. Before that, it was mostly a process of transplantation, imitation, and exploration. Though there were eight schools, the two that stood out in terms of longevity, numbers of adherents, and influence were Chan and Pure Land.

Chan was mainly for people with advanced abilities and received high acclaim, especially during the Tang and Song dynasties, which had a wealth of capable practitioners. Its momentum did not slacken until recent times, and it became the mainstream of Chinese Buddhism.

Pure Land accommodated practitioners of all capabilities, with average and lower ability as the mainstay. When practicing Pure Land, even those of superior ability considered themselves among the less adept, adopting extremely low profiles and exercising influence discreetly. Pure Land became the Dharma school with the most followers and the deepest roots in society. After all, practitioners with average and lower abilities far outnumbered those of advanced aptitude.

The Chan and Pure Land schools had close interactions, either openly or subtly, directly or indirectly. Chan provided the form, Pure Land the substance. Chan served as a guide, and Pure Land was the destination. It was during the Song dynasty that Master Yongming advocated a fusion of the Chan and Pure Land paths, steering followers of the former toward the latter. Subsequent patriarchs continued this course until Master Yinguang in modern times promoted Pure Land teaching and practice exclusively. The baton of Chinese Buddhism can be said to have passed from Chan to Pure Land. As Master Taixu of the Republican era said, “All Chinese Buddhism can now be summed up in a single recitation of ‘Amitabha Buddha.’”

The Pure Land path of Amitabha-recitation was affirmed and promoted by the entire Buddhist community in China. It became the summation of Chinese Buddhism, the school with the most followers and the broadest foundation of faith. It was the greatest common factor of Buddhism in China.

Having received the baton, the Pure Land school must shoulder the heavy responsibilities of running the next leg of the relay. Clearly, it is not realistic to discuss the future development of Chinese Buddhism without considering the foregoing historical background and realities.

ii) The call of the times

If we look around, we can see that we are living in an era of complete other-power. Social productivity is continually rising and the division of labor is increasingly meticulous. Transportation, communications, the Internet . . . in everyday life, we are relying more and more on other people. The self-sufficiency of the agrarian era is long gone; these are times of intensive other-power karma. From food and clothing to transportation and travel, and communications and shopping—everything is intangibly providing proof of that.

What kind of Buddhism do people of the current era need? Shakyamuni Buddha said, “The world is a projection of the mind, and the external environment reflects our inner state.” When those who live in the material world are so dependent on other-power, they would be all the more so in their invisible spiritual life.

In the Amitabha-recitation of the Pure Land school, we rely entirely on Buddha-power. Reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha is simple, easy, and can be done by anyone. Amitabha’s vows ensure that everybody can achieve rebirth in the Land of Bliss. The path is most suited to the needs of contemporary people. It is practical, functional, and efficacious, capable of benefitting modern people amid the rush of their busy lives. They will be at ease in life and unafraid of death. In this life and the next, they will feel complete and happy.

iii) The prediction of the Buddhist scriptures

In various sutras, Shakyamuni Buddha stated clearly that after he entered nirvana, his teachings would pass successively from the Age of Right Dharma (500 years), through the Age of Semblance Dharma (1,000 years) and to the Age of Dharma Decline (10,000 years). Then would come the Age of Dharma Extinction.

The Great Collection Sutra says, “In the Age of Dharma Decline, billions may practice but hardly one will accomplish the path. The cycle of rebirth can be transcended only through recitation of Amitabha Buddha’s name.” The Infinite Life Sutra states: “In times to come, the sutras and the Dharma will perish. But out of pity and compassion, I will retain and preserve this sutra for a hundred years more. Those sentient beings that encounter it can obtain deliverance as they wish.” We are now a thousand-odd years into the Age of Dharma Decline. It is precisely the time for the Pure Land path of Amitabha-recitation to come into its own and become popular.

iv) Factual evidence

When people see monks, the first thought they have is “Amitabha.” In any temple, the first thing one sees is “Namo Amitabha Buddha.” In every monastery, the Amitabha Sutra is invariably chanted during morning and evening services. When monastics or lay Buddhists pass away, people recite “Namo Amitabha Buddha” to help them gain rebirth in the Land of Bliss.

In traditional monasteries, Chan meditation halls are closing one after another. But in cities and villages, centers for Amitabha-recitation are sprouting everywhere. Gaining enlightenment via the other schools is rarely reported, while rebirth in the Pure Land through Amitabha-recitation is regularly witnessed. If Chinese Buddhism hadn’t retained the imperishable spark of rebirth through recitation, it might have become history already.

Hongyuan Monastery in Anhui Province. From Pure Land Buddhism facebook

Hongyuan Monastery in Anhui Province. From Pure Land Buddhism facebookv) New hope

Throughout the ages, even though the Pure Land path of Amitabha-recitation was well developed in China, it had not fully demonstrated its vitality. The main constraints involved principle and practice. Regarding the former, three masters, Tanluan, Daochuo, and Shandao had established during the Sui and Tang dynasties a complete system of thought for Pure Land Buddhism. However, the tradition wasn’t passed on. After the Huichang Buddhism persecution of the late Tang and the chaotic wars of the Five Dynasties period, the transmission was lost in China. In subsequent times, successive generations in China learned Pure Land principles by relying on interpretations by the Tiantai and Huayan schools. As for practice, they were heavily influenced by the self-power orientation of the Chan school. That was why the uniqueness of Pure Land deliverance, through the power of Amitabha’s Fundamental Vow, could not be fully expressed.

It was only a century ago that the writings of Tanluan, Daochuo and Shandao returned to China from Japan. This laid the theoretical foundations of a new era for the Pure Land school. Now, it has become a trend in Buddhist and academic circles to study the thought of Master Shandao and practice according to his teachings. The first light has dawned on a renascence of the Pure Land school.

There are four special characteristics to Master Shandao’s Pure Land thought. The first is that the school has its own independent, systematic principles for Dharma classification. It does not need to borrow anything from other schools. Secondly, with the guiding principles of “accepting and having faith in Amitabha’s deliverance” and “single-mindedly reciting Amitabha’s name,” Pure Land is no longer subject to the self-power influences of the other schools. Third, it stresses “recitation of Amitabha’s name, relying on his Fundamental Vow,” “rebirth of ordinary beings in the Pure Land’s Realm of Rewards,” “rebirth assured in the present lifetime,” and “non-retrogression achieved in this lifetime.” The benefits are even broader and more complete, with practitioners being reborn directly in the Pure Land’s Realm of Rewards. Benefits also accrue in the present lifetime.

Finally, Pure Land Buddhism is itself classified into the “Path of Importance” and the “Path of the Great Vow.” This expediently makes use of the former, with its “dedication of merit from meditative and non-meditative virtues toward rebirth in the Pure Land,” to incorporate the practices of all other schools into the Pure Land tradition. The result is a system of Pure Land thought that is complete, rigorous, and highly flexible in its functioning. It establishes the thought and perspectives of Pure Land from various eras, lending order and coherence to more than a millennium of Pure Land developments. Creating a scenario where there was a pooling of efforts to teach sentient beings and end doctrinal disputes, it boosts unity among Pure Land practitioners.

This essay is not an in-depth investigation of Dharma principles. But with many years’ experience of Dharma study and propagation, the monastic sangha of Hongyuan Monastery firmly believes that the Chinese Pure Land school established by Master Shandao during the Sui and Tang dynasties can bring about a modern transformation of Chinese Buddhism. Suited to the characteristics and capabilities of the contemporary public, it can open the path to a new future.

Some specific actions that would facilitate such a transformation:

1) Strengthening the study of theory

Theory, or doctrine, guides practice. We should take the three Pure Land sutras spoken by Shakyamuni Buddha and the commentaries of our lineage masters as the backbone, then incorporate teachings of the other schools and worldly virtuous practices into a theoretical structure comprising Ultimate Truths and Worldly Truths. We must also emphasize practical applications in today’s society.

2) Legalizing Amitabha-recitation centers

Chinese Buddhism has a long tradition of practitioners forming recitation centers. Pure Land practitioners believe deeply in karma, are mindful of impermanence, and are modest. Illuminated by the compassionate light of Amitabha Buddha, they have an anchor in life. Their hearts are serene, at peace, and they are a source of positive energy in society. An Amitabha-recitation hall is like a spiritual green park in a community. It nurtures the elderly, diminishes societal pressure, lifts negative sentiment, and purifies the heart and mind. It helps stabilize and harmonize society, as well as resolve conflict. And it does all this in a subtle manner.

Amid today’s emphasis on the rule of law in national affairs, it is essential to register recitation halls in all parts of the country according to the law. It will guarantee that their positive energy is transmitted to society.

3) Enhancing organizational structure

The present structure is that the Buddhist Association of China, at all levels, is under an administrative subdivision of the government. In some places, the bureaucratic style is onerous and out of touch with practitioners. They even become arenas for the pursuit of fame and material gain. Perhaps the authorities can permit believers to independently establish and register Buddhist organizations—such as Buddhist youth study groups or Pure Land associations. That would create a competitive mechanism and encourage the construction of a style and specific characteristics for Buddhism. It would also foster closer ties and communications between party and government officials, and practitioners.

4) Emphasizing the development of skilled speakers

We should actively promote the tradition of Dharma discourses, emphasizing the actual experience and functionality of talented speakers. We need to develop a team of speakers whose beliefs are correct and whose Dharma knowledge is specialized. They should be well received by audiences, and needed by the nation.

Take, for example, the Pure Land talent-development program of Donglin Monastery, as well as the “Assessment and Certification Method for Lecturers of the Pure Land School” venture now under way at Hongyuan Monastery. Such initiatives to nurture Buddhist talent, centered on specific Dharma centers, are commendable experiments.

5) Speeding up religion-related legislation

At present, laws relating to religion are skimpy, fragmented, and unsystematic. In some places, religious affairs are handled opportunistically and arbitrarily. Some people hold on to leftist thinking and show little tolerance for religion. They think up all sorts of restrictions, artificially raising tensions. Other places are overly lax, with religion-related activities being undertaken in the name of the government, thereby violating the legal rights of the religious community. From a global perspective, conflicts that arise between different faiths and sects often create more conflict. They cause much unease. How can an increasingly open and religiously diverse China avoid disputes resulting from religious pluralism? All these issues require clearer legal norms.

Finally, because of limitations in the author’s knowledge and perspective, this essay will inevitably contain points that may seem stark or impudent. May it benefit from corrective comments by all esteemed practitioners and big-hearted bodhisattvas who care about the future of Buddhism in China.

This essay was written by Master Jingzong in 2015. English translation by Householder Jingfa, edited by Householder Jingtu.

This article is part of “Buddhism in the People’s Republic,” a special project focusing on the schools of Mahayana Buddhism in contemporary China. Through this project, Buddhistdoor Global’s editorial team and expert contributors aim to provide a concise, insightful, and informative overview of the history of contemporary Chinese Buddhism, and the modern practices and influences that are shaping the changing face of modern China. Return to Buddhism in the People’s Republic