FEATURES|COLUMNS|Exploring Chinese Buddhism

Buddhism in Contemporary China Through a Photographer’s Eye

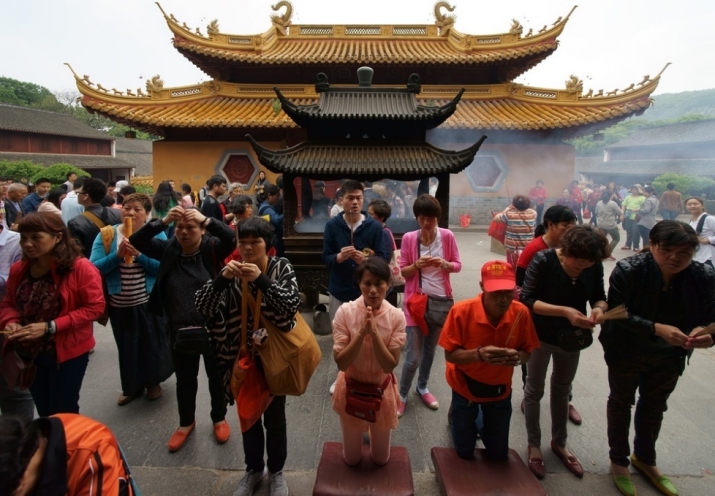

Pilgrimage, Putuo Monastery, Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, 2015. Photo by Yang Liquan

Pilgrimage, Putuo Monastery, Zhoushan, Zhejiang province, 2015. Photo by Yang LiquanAccording to the Washington, DC-based Pew Research Center, 18.2 per cent of China’s population—that is 224 million people—are Buddhists, accounting for about half of the world’s total Buddhist population.* But what do these figures mean? They reveal little about what Buddhism is like in China today. Photographer and filmmaker Yang Liquan is one of the few people who can shed some light on this question. For the past 40 years, from Lhasa to Beijing, Yang has been producing photographic catalogues and documentary films of Buddhist communities and heritage sites all over China.

A Buddhist ritual performed at Bailin Chan Monastery, Zhao County, Hebei Province, 2013. Photo by Yang Liquan

A Buddhist ritual performed at Bailin Chan Monastery, Zhao County, Hebei Province, 2013. Photo by Yang LiquanBetween May 2013 and May 2016, Yang served as artistic director on the documentary project Fojiao shengdi xing (佛教聖地行; Pilgrimages to Buddhist Sacred Sites), initiated by Religions in China magazine, the State Administration of Religious Affairs, and the Chinese Buddhist Association. Of the 33,000 Buddhist monasteries in China, the production team of 15 members visited 270 major sites and interviewed 145 eminent monks. “On average, we selected 5–10 monasteries in each province. In Shanxi, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, where Buddhism is flourishing most strongly nowadays, around 20 monasteries were documented in each province,” Yang told me.

Morning at Langmu Monastery, Gansu Province. Photo by Yang Liquan

Morning at Langmu Monastery, Gansu Province. Photo by Yang Liquan Xiantong Monastery, Wutaishan, Shanxi Province. Photo by Yang Liquan

Xiantong Monastery, Wutaishan, Shanxi Province. Photo by Yang Liquan“In each monastery, we photographed and filmed the architecture and monastic life in detail, and documented historical information and interviews. When it came to important monasteries, it could take up to a week to finish all the work. These materials will be presented to the public in books, documentaries, and exhibitions in the near future,” Yang, who turned 60 this year, explained. “Our purpose is to provide a comprehensive survey of Chinese Buddhism today and spread such knowledge. We were fortunate enough to interview influential members of the sangha before they left us, for instance Venerable Gentong (根通, 1928–2016), former director of the Shanxi Buddhist Association, and Venerable Kok Kwong (覺光, 1919–2014), the first president of the Hong Kong Buddhist Association.

Young monks at Basu Monastery, Chamdo, Tibet, 1986. Photo by Yang Liquan

Young monks at Basu Monastery, Chamdo, Tibet, 1986. Photo by Yang LiquanAmong the monasteries he has documented, Yang was impressed by the de-commercializing efforts of Nanputuo Monastery (南普陀寺) in Fujian Province. Unlike most monasteries in China, it does not charge an entry fee, and even provides free incense to devotees. Each year, the monastery attracts 6 million visitors. Kaiyuan Monastery (開元寺) in Jiangsu Province is notable for having embraced the digital age, adopting a modern management system by computerizing the monastic records of sangha members, as well as its legal affairs and finances.

Labrang Monastery, Xiahe, Gansu Province, 2014. Photo by Yang Liquan

Labrang Monastery, Xiahe, Gansu Province, 2014. Photo by Yang Liquan Wild donkeys in Hoh Xil, Tibet, 1990. Photo by Yang Liquan

Wild donkeys in Hoh Xil, Tibet, 1990. Photo by Yang LiquanI asked Yang how he had found his niche photographing Buddhist themes. He revealed an obscure but eventful history going back to 1972, when he was 16 years old. Yang was among a group of teenagers selected to be students of the Qinqiang Opera Troupe of Tibet. They traveled to Lhasa by truck all the way from their homes in Shaanxi Province, a journey that took about one-and-a-half months. Yang performed in a dozen shows around Tibet before the troupe was dismissed in 1975, then he stayed on and started learning painting and photography. Over the next 20 years, Yang worked as graphic designer and photographer for the Tibet Exhibition Center, the Film Distribution Company of Tibet, and the Tibet Youth Journal.

Drepung Monastery, Lhasa, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang Liquan

Drepung Monastery, Lhasa, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang Liquan“I had not known anything about Tibet or Buddhism before I went there,” Yang recalled fondly. “Some of my relatives worked with the opera troupe, so I grew up hearing about how beautiful Tibet was. I was simply very excited to be able to go there. At that time, there was a very amiable atmosphere between Tibetans and Han Chinese.”

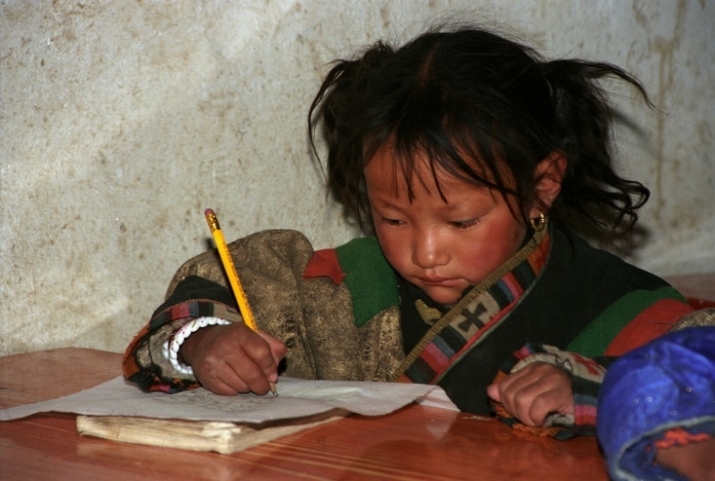

Yang’s work took him all over Tibet and offered him the opportunity to document various aspects of Tibetan culture between the late 70s and early 90s. In one project, Yang and his Tibetan colleagues were sent to collect data and report on education in rural areas. “Once, we lived for two months in Kekexili [also known as Hoh Xil] in the northwest of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, one of the least-populated regions on Earth. But I felt more human than at any other time in my life. That’s what touched me most about Tibetan culture and religion—the harmony between humans and nature.”

Portrait, Shigatse, Tibet, 1982. Photo by Yang Liquan

Portrait, Shigatse, Tibet, 1982. Photo by Yang Liquan Portrait, Lhasa, Tibet, 1989. Photo by Yang Liquan

Portrait, Lhasa, Tibet, 1989. Photo by Yang LiquanIn 1994, Yang moved to Beijing for a new job opportunity with a publisher. It was around that time that many Han Chinese were starting to be drawn to Tibetan Buddhism, as they saw it as purer and more authentic than Chinese Buddhism. When I asked about this phenomenon, Yang responded, “The teachings preserved in Tibetan Buddhism are more systematic. Their visual arts are unique, shaped by local traditions as well as by Indian and Nepalese influences. However, I don’t think it is meaningful to say which is better or superior. In essence, Tibetan Buddhism and Chinese Buddhism are not different. Esoteric elements can be found in both schools.”

Portrait, Hoh Xil, Tibet, 1990. Photo by Yang Liquan

Portrait, Hoh Xil, Tibet, 1990. Photo by Yang Liquan“I think Buddhism plays a very positive role in at least five areas of our society—education, charity, self-cultivation, art and architecture, and international cultural exchange,” he continued. “Both the sangha and the lay community have been actively raising and donating funds for pre-college education and to care homes for seniors. When Vladimir Putin came to China in 2006, he paid a special visit to Shaolin Monastery (少林寺), which is renowned worldwide for its martial arts.”

Galden Jampaling Monastery, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang Liquan

Galden Jampaling Monastery, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang LiquanYang has great respect for Buddhism, especially the concept of the Middle Way, but he himself has never converted. “I am happy living in monasteries and eating vegetarian meals. When I am with non-Buddhist friends, I am also fine with whatever is on the dinner table. One shouldn’t deliberate over these matters,” he observed. “The Buddha ate whatever he was given.” When asked about the future of Buddhism in China, he calmly reflected, “I think Buddhism is going to disappear eventually. The number of monasteries and members of the sangha are declining. Rise and fall, it is all part of the process.”

Buddhist ritual at Garzê, Sichuan Province, 2015. Photo by Yang Liquan

Buddhist ritual at Garzê, Sichuan Province, 2015. Photo by Yang Liquan Portrait, Tingri, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang Liquan

Portrait, Tingri, Tibet, 1998. Photo by Yang LiquanYang is currently working on a project documenting Buddhist monasteries around Beijing. In his spare time, he takes portrait photos of his friends of different backgrounds. “I want to document these people and capture their personalities. It would be nice if people after us could learn about what our time is like from these photographs,” he said, a smile, genuine and warm, lighting up his face.

* Global religious landscape – Buddhists (Pew Research Center)