Dr. Lisa Kemmerer is a philosopher-activist dedicated to working against oppression, whether on behalf of the environment, nonhuman animals, or disempowered human beings. Her books include In Search of Consistency: Ethics and Animals; Animals and World Religions; Sister Species: Women, Animals, and Social Justice; Call to Compassion: Reflections on Animal Advocacy; Speaking Up for Animals: An Anthology of Women's Voices; and Primate People: Saving Nonhuman Primates through Education, Advocacy, and Sanctuary. Kemmerer has hiked, biked, kayaked, backpacked, and traveled widely, and is currently associate professor of philosophy and religions at Montana State University Billings.

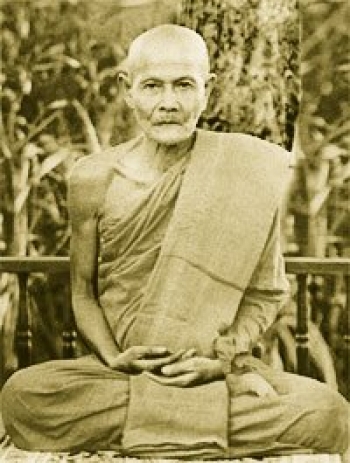

The form and function of spiritual adepts are cross-cultural. Buddhist Arahants, such as Acharn Mun, a Thai Buddhist in the early nineteenth century, like Christian saints, are tangible, contemporary symbols of spiritual belief and practice modeled on the founder. They inspire veneration and evoke imitation, drawing people to heightened spirituality. Magical powers are attributed to Arahants, as to saints, and for both spiritual elites, their associations with the larger public are essential to their material well being and their acclaim. Saints and Arahants provide a bridge between marginalized peripheral populations and those dwelling at the center of a metropolis, linking the poor with the wealthy, the powerless with the reigning powers.

The Buddha, like Jesus, continues to be a living model for those who choose to walk the spiritual path. Arahants gain their spiritual powers and elite status over time, through rigorous religious practices such as meditation, study, and asceticism—through practicing the spiritual ideals of Buddhism. The life of an Arahant is both a carbon copy of the life of the historic Buddha, and a contemporary example of living the Buddhist life. Arahants offer a living model of Buddhist life for devotees to imitate, just as saints provide a living example of those who honor the life of Jesus.

The religious ideal, exemplified in contemporary Arahants such as Acharn Mun, was set by one no less than the Buddha. From an early age, Mun was committed to meditation. Reports indicate that he practiced rigorous asceticism, ate only once a day, and wore rags.

Through intense practice, Mun was reputed to have gained supernormal powers, or Iddhi. Arahant supernormal powers include flying through the air unaided, a clear vision of past lives, and the ability to tame demons and fearsome wild beasts. Reports indicate that Mun could also understand the language of other creatures, knew what other people were thinking, and banished a powerful demon from a cave. Saints are most often credited with healing powers.

Though supernormal powers seem wondrous in themselves, Iddhi are secondary to higher spiritual goals such as mastering meditation, understanding the Dharma, and attaining Nirv??a. Iddhi are mere side effects believed to stem from spiritual wisdom and purity, but it is the spiritual wisdom and purity that are important, not the side effects. Such powers must be set aside if the spiritual adept is to achieve the highest religious goal.

Still, supernormal powers are important because they demonstrate spiritual accomplishment, and attract a following. The greater the spiritual achievements, the more iddhi, and the more acclaimed the Arahant will become. Mun was credited with extraordinary wisdom, love, and charismatic powers (Tambiah, Buddhist Saints 3).

The greater the acclaim, the more honored among devotees, the stronger that particular Arahant's field of merit. Arahants are able to reach such a high state of wisdom and purity that they have a considerable field of merit, and those who are willing can share this merit with devotees. Individuals who come to visit the Arahant gain religious merit through the holiness of the saint. Devotees bring gifts or hear teachings; through respect, reverence, generosity, and imitation of the saint, devotees are able to plant positive spiritual seeds for their future. When devotees pay homage to Arhants (or Buddhist images), “goodness is caused to arise within them because the relics and images act as a field of merit in which men can plow, plant, and produce fruits (Tambiah, Buddhist Saints 201).

Acharn Mun was widely sought by devotees in search of spiritual merit. Attending to the needs of an Arahant is a meritorious. When devotees attend Arahants they receive spiritual benefits, or earthly good fortune, as a result of such attendance. Gift-giving, feeding an Arahant, and listening to an Arahant’s dharma lessons are all meritorious. Each act of devotion toward an Arahant is also an act of lovingkindness that will bring higher mental formations, and spiritual progress because of the Arahants enlarged field of merit. Just as saints in the Christian tradition can intercede between God and the faithful, Buddhists can “go through” an Arahant to gain from his or her field of merit.

While laity turn to Arahants to fulfill spiritual needs, Arahants depend on devotees for material goods. Arahants establish strong bonds with disciples. On festival days monks and Arahants are honored with special feasting and gift-giving of material necessities, such as robes. In exchange for food and clothing, Arahants offer Buddhist teachings. In the event that an Arahant should become popular and decide to found a monastery, as with the Christian saints, gifts from the laity and the larger religious community create and maintain the buildings, and provide for the ongoing needs of the monks.

Arahants also depend on followers for acclaim. Disciples may form neighboring monasteries, which help to spread the fame of the senior Arahant. Disciples of Acharn Mun never fail to call attention to their connection with this worthy Arahant, whose powers they share by virtue of the master/disciple relationship. Through an expanding discipleship, and through his many devoted lay followers, an Arahant's reputation can spread even to national acclaim, though they live quiet lives in remote regions.

Arahants do not live at the spiritual center. They most commonly establish forest hermitages in the unsettled periphery of Northern Thailand, where they wander, teach, and meditate. The most powerful Arahants have spent long periods of time in mountainous jungles, where they live as ascetics in wilderness caves. Like St. Francis and Mother Teresa from the Catholic faith, Arahants tend to live in remote regions. Like Christian saints, Arahants bring a civilizing, unifying message of Buddhism to peoples who are cut off from the center of Buddhist Thailand.

Mun frequented jungles and caves, and established a temple just outside the little village where he lived as a boy. Though he lived on the periphery, Mun brought established Buddhist ideals and values to remote regions, an important role that Arahants share with Christian saints. As with St. Francis and Mother Teresa, Mun’s following started among the humble people who lived in the outlying areas where he practiced asceticism and meditated.

Pilgrimages pull those who live in population centers out to the periphery, connecting those with shared belief across both miles and social strata. As Mun’s fame spread, news of this Arahant reached the highest strata of Thai society. Nobility and kings, bankers and high government officials, all make pilgrimages to well-known Arahants in Thailand, including Mun, providing strong financial backing to such Arahants and their disciples. When a famous Arahant such as Mun dies, the Thai king is also likely to attend the cremation ceremony, and perhaps even take home a relic. Through such a pilgrimage, the king expresses shared religious ideals, honoring those who are at the top of the spiritual hierarchy even as they honor the king—the top of the political hierarchy. The community is unified: the king supports the faith of the people; religious leaders, in turn, support political leaders by receiving them for ceremonies and special occasions.

Pilgrimages pull those who live in population centers out to the periphery, connecting those with shared belief across both miles and social strata. As Mun’s fame spread, news of this Arahant reached the highest strata of Thai society. Nobility and kings, bankers and high government officials, all make pilgrimages to well-known Arahants in Thailand, including Mun, providing strong financial backing to such Arahants and their disciples. When a famous Arahant such as Mun dies, the Thai king is also likely to attend the cremation ceremony, and perhaps even take home a relic. Through such a pilgrimage, the king expresses shared religious ideals, honoring those who are at the top of the spiritual hierarchy even as they honor the king—the top of the political hierarchy. The community is unified: the king supports the faith of the people; religious leaders, in turn, support political leaders by receiving them for ceremonies and special occasions.

Relics, distributed after death, are assumed to be powerful, to carry blessings and merit, and to offer good fortune. Places the saint visited during his or her life are also likely to become places of pilgrimage for those who hope to tap into the spiritual powers of the deceased. Devoted followers continue to pay homage to the Arahant, just as they continue to honor the Buddha, both of which offer spiritual benefits. Similarly, Catholics are likely to visit the orphanage of Mother Teresa in Calcutta, the body of St Xavier in Goa, and the Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi. While we ourselves may not attain perfection, others have, and by honoring those special others, we express our commitment to the spiritual ideals of our faith, and draw ourselves closer to those ideals and the benefits that coincide with practicing those ideals.

Arahants, like the Buddha, are expendable in the individual's quest toward the ultimate truth, which is merely symbolized by the spiritual adept. Fundamentally, the phenomenon of the Arahant arises from human desire to grasp and be nearer spiritual ideals, to gain spiritual merit, and ultimately to attain the highest spiritual goal, even though that goal ultimately lies beyond even the Arahant. The ultimate goal in Buddhism, as in Christianity, lies within the individual, and beyond the individual.

Forest Arahants of Thailand match the model of sainthood, but this is not to say that saints and Arahants are identical. There are many differences. For example, the powers of an Arahant are inherent—residing in the individual—and are not attributed to a deity. An Arahant reaches a holy state through personal effort, while a Christian saint experiences the gift of the divine. Both must invest considerable effort and determination, but the Christian saint is not understood to act alone. Similarly, expectations after death are different for an Arahant and a saint: while the Christian saint hopes to dwell with God, the Arahant hopes to experience nirvana. Buddhist saints are neither dependent on the divine nor in search of the divine.

In spite of such important differences, the form and function of spiritual adepts are cross-cultural. Saints and Arahants are both tangible, contemporary symbols of spiritual belief and practice. They are catalysts that inspire veneration and evoke imitation, drawing people to heightened spirituality. Saints and Arahants are believed capable of magical or miraculous acts, of granting boons and good fortune, healing, and assisting people on their spiritual journey. Saints and Arahants are both dependant on an exchange with laity: spiritual benefits are exchanged with material necessities. Furthermore, a strong following can bring acclaim, fame, and yet more material benefits and spiritual reknown. Saints and Arahants draw peripheral populations into the larger fold.

The Buddhist and Christian traditions share the phenomenon of spiritual adepts. While one is called an Arahant, and the other a saint, their roles are similar. These exceptional individuals continue to be critical to religious faith and practice. Saints such as Acharn Mun provide a living model of the ideal spiritual life, and inspire others to walk a more rigorous path of religious practice and devotion.

Bibliography

Hawley, John Stratton, ed. Saints and Virtues. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Kieckhefer, Richard and Bond, George D., eds. Sainthood: Its Manifestations in World Religions. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1988.

Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. The Buddhist Arahant: Classical Paradigm and Modern Thai Manifestations, Saints and Virtues Ed. Hawley, John Stratton. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987, 111-126.

The Buddhist Saints of the Forest and the Cult of the Amulets, A study in Charisma, Hagiography, Sectarianism, and Millennial Buddhism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.