Introduction

Buddhist economics is an important issue for the lay person as it is a daily concern. A Buddhist lay person has to work to maintain daily living as well as to support his/her own immediate families and contribute to society. However, one has to do so within the confines of Buddhist ethics to make spiritual progress.

Buddhist economics is a large topic covering many areas including Right livelihood, Appropriate spending, Attitude to wealth, Economic ethics for rulers, Monastic and laity economics, and the Justice of economic distribution. In this article I will just focus on the attitude to wealth in Buddhism.

The Buddhist teaching advocates detachment and ending craving whilst it censures indulgent sensual pleasures. The bodhisattva abandoned a life of luxury to seek for enlightenment and even when he attained it he continued to live without much material possessions other than the minimal requisites. Indeed, a Buddhist novice has to renounce all his worldly possessions before he is allowed to enter monkhood. Buddhist scriptures [suttas] document significant number of monks came from well off backgrounds. In addition, certain Buddhist practices might be characterised as ‘ascetic’, such as eating one meal a day. One might thus conclude from all this that Buddhism does not have a positive attitude towards wealth. However, this view would not be in line with the Buddhist teaching. Furthermore, there is different attitude to wealth with regards to the ordained clergy (monks and nuns) and the laity.

Poverty

In Buddhism, lay people are expected to maintain livelihood for their own, their families’ and society’s welfare. Basic needs must be met before one can concentrate on spiritual development. It would be difficult to develop calmness if one is not physically well or one is worrying about financial concerns. Even hunger is enough to disturb the mind to the extent that it becomes difficult to concentrate. In one sutta, the Buddha came to a village to teach a man whom he saw as capable of attaining insight. However, when he got there the man was so hungry and tired that the Buddha asked for him to be fed before delivering the discourse which helped him gain insight.[1] Elsewhere in the Scriptures the Buddha said, ‘Hunger is the greatest illness’.[2] Similarly, one cannot have peace of mind when one is excessively worried about financial affairs, such as debts and therefore, ‘for householders in the world, poverty is suffering’[3] .

Not only poverty does not provide people with basic needs it also does not give them as much opportunity to practice generosity and thus accumulate merit. More importantly though, poverty is also seen as one of the causes of social problems, such as crime and violence. In one sutta, the Buddha described how poverty led to social problems such as stealing, killing, lying and shortened lives.[4] For lay people therefore, poverty creates suffering both on a personal and social level; and hence for them, ‘woeful in the world is poverty and debt’.[5]

Wealth

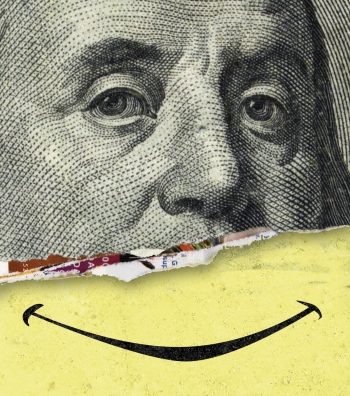

We’ve seen above that poverty and debt in Buddhism is suffering for a lay person. Does this mean that Buddhism advocates amassing wealth? In fact, in Buddhism wealth itself is neither praised nor reproved, only how it is accumulated and used. Wealth is blameless if it is rightfully obtained, without hurting others, i.e., without violence, stealing, lying and deception. This is Right Livelihood and it is one of the factors of the Noble Eightfold Path (the Buddhist Path). Thus, wrong livelihood would include trades which involve killing, directly and indirectly such as butchery and trading in arms respectively. It also includes trades which involve frauds and deception. Even marketing is considered wrong livelihood to the extent that more often than not involves a certain amount of deception (making the products more appealing than what it is) and also it draws on people’s aspirations, prejudices and desires (Payutto, 1994). On a more subtle note, even right livelihood can sometimes be considered wrong if it is practiced with the wrong motivation, for example a doctor who recommends medicine that is not really necessary for the patient’s condition.

Buddhist Scriptures introduced the notion of being ‘two eyed’ when it comes to making a living. One has to keep one eye on profit and the other on ethics. According to the Scriptures, there are three kinds of people in the world: they are the blind, the one-eyed and the two-eyed. The blind person does not know how to generate wealth, does not know what is right and wrong, and does not know what is good and bad. This person has no wealth and cannot perform good works (such as giving gifts, making donations, etc). The one-eyed person knows how to generate wealth but does not know what is blameworthy or not, and what is good or evil. This person may thus obtain wealth through whatever means including violence, theft and deception. Though he/she enjoys sense pleasures from the wealth generated, when he/she dies is reborn in hell. The two-eyed person knows how to generate wealth, but also knows what is right and wrong, blameworthy or not, and whether it is good or evil. This person enjoys his/her wealth in this life but also after death is reborn to a good destination.[6]

How to accumulate wealth

Though it is thought that wealth can be the result of a good rebirth, a karmic consequence of generosity, other factors contribute towards financial success and happiness are:

1. Industriousness - energetic striving in one’s job.

2. Watchfulness - taking care of one’s property to prevent lost due to robberies and natural disasters such as flood.

3. Having good friends - so one can emulate their actions.

4. Leading a balanced life - one does not spend excessively nor hoards wealth. Also, one should remain equanimous in the vicissitudes of life.[7]

On the other hand, wealth can be dissipated by:

1. Addiction to drink/drugs.

2. Haunting the streets at night - leaving one’s property unprotected.

3. Addiction to entertainments and amusements and always on the look out for them.

4. Addiction to gambling.

5. Keeping bad company such as gamblers, drunks and fraudsters.

6. Habitual idleness - one is too lazy to do anything.[8]

How to use wealth

In Buddhism, wealth is a means to an end. It can either be a benefit or a burden depending on one’s attitude to wealth and how one uses it. It helps to provide basic needs and offers the opportunity to develop generosity from giving. But if one is obsessed with wealth, one goes through much hardship attaining it, one creates bad karma from unethical practices, and spending it unwisely creates suffering. Once wealth is obtained, according to the Sigalovada Sutta, one should invest half of it into business, use a quarter of it for enjoyment and save the rest.[9] Elsewhere, the Scriptures advice wealth should be used in the following way:

1. To bring happiness to oneself, families, friends and employees.

2. Protect one’s wealth against loss.

3. Give offerings to relations, guests, dead relatives and gods.

4. Give gifts to virtuous people, such as monks and nuns.[10]

The Buddha said there are four kinds of happiness for the layman who enjoys the pleasures of the senses. The happiness that comes from ownership, happiness from consumption, happiness of knowing that one is free from debt, and the happiness of blamelessness in thoughts and deeds.[11]

However, if wealth is not properly used it does not bring happiness and enjoyment. For example, gambling can make one more miserable and drinking can lead to quarrels and fights. On the other extreme, if one is miserly one does not enjoy wealth nor let others enjoy it, such a person is described as being like ‘a forest pool in a haunted forest - the water cannot be drunk and nobody dares to use it’[12] . Wealth should not be enjoyed alone, and the Buddha’s advice is, ‘…if people knew, as I know, the fruits of sharing gifts, they would not enjoy their use without sharing them, nor would the taint of stinginess obsess the heart. Even if it were their last bit, their last morsel of food, they would not enjoy its use without sharing it if there was someone else to share it with’[13] .

Relevant to the use of wealth is the concept of ’right consumption’ brought up by Ven. Payutto. According to him right consumption is the use of goods and services for well-being whilst wrong consumption, arises from craving, is the use of goods and services to satisfy pleasing sensations and ego-gratification (Payutto, 1984). A simple example of this would be buying the latest most expensive brand product to boost one’s ego instead of a much cheaper one that does the same job.

Two notions of poverty

It is important to differentiate between poverty and renunciation (voluntary possessionlessness) which on a superficial level appears similar. Mavis Fenn in a paper in 1996, discussed these ‘two notions of poverty’. On one hand, ‘Poverty, understood as deprivation signifies all that divides us from each other; it signifies the abuses that arise from unbounded structure’[14] whilst wealth is seen as promoting peace and harmony in a social-political context. On the other hand poverty, ‘possessionlessness, religious poverty, signifies all that unites us and reminds us of our connection with each other, the natural world, and the cosmos’ whilst wealth is seen as an obstacle to the religious life (Ibid). She notes that sometimes both attitudes towards poverty appear in the same text, such as the Cakkavatti-Sihanada and the Kutadanta Sutta[15] and this seems to emphasize the paradox. Yet this paradox is resolved by the fact that the Sangha [Buddhist monastic community] ‘symbolically provides a filter between itself and the pollution that wealth bring with it, and the spiritualization of giving turns the receipt of gifts into a means by which the Sangha exercises its mandate to assist others in their spiritual development [thus]…As poles apart they signify the paradox of human existence. The dynamism created from their struggle towards a better vision of what it means to be human and in community’.[16]

Monks and nuns devote all their time to spiritual development. They rely on the lay people for their material welfare and they provide spiritual guidance in return. Since they rely on donation from lay people, monks and nuns have minimal material possessions so they don’t become a burden on them. Having fewer possessions also mean they have less concerns about them. Furthermore, being content with little is a quality emphasised in Buddhism. However, the monks’ basic needs are still met, whereas lay people may lack such basic needs if they do not have livelihoods or someone who can support them financially.

Conclusion

The Buddhist teaching on wealth is an important issue for the lay person as he/she needs to practice Right Livelihood as part of the Buddhist Path. Buddhism recognises that wealth can bring comfort and enjoyment or misery to householders both in this and future lives. Happiness is procured by recognising a balance between economics and ethics, ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ consumption, and achieving the ‘Middle-way’ between materialism and asceticism. The role of wealth is to provide adequate basic needs for oneself and society but not to the extent that it encourages greed and indulgence. Hence, Buddhist value is in tension with the materialistic consumerism. As de Silva puts it, ‘it [Buddhism] advocates that we feed our needs and not our greeds’[17] . In Buddhism, wealth is not evil but avarice is, therefore, ‘Wealth destroys the foolish, but not those who search for the Goal [Nirvana]’[18] . The function of wealth is to provide contentment, which serves as a solid foundation for spiritual development. Hence, being contented with little is a quality much emphasized in Buddhism, ‘Contentment is the greatest wealth’ (Dhp.204).

Abbreviations

A. = Anguttara Nikayas (5 Volumes)

D. = Digha Nikayas (3 volumes)

Dhp. = Dhammapada

S. = Samyutta Nikayas (5 Volumes)

It. = Itivuttaka

D. = Digha Nikayas (3 volumes)

Dhp. = Dhammapada

S. = Samyutta Nikayas (5 Volumes)

It. = Itivuttaka

References

1.Harvey, P., An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, 2000, CambridgeUniversity Press.

2.Ven. P. A. Payutto. Buddhist Economics - A Middle Way for the market place, translated by 3.Dhammavijaya and Bruce Evans, 1994, http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Academy/9280/econ.htm#Contents

4.Lily de Silva, 'Livelihood and Development', part of her One Foot in the World:http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/wheels/wheel337.html#dev

5.Mavis Fenn, Two Notions of Poverty in the Pali Canon, Journal of Buddhist Ethics, Vol.3 (1996), pp.98-125:http://jbe.gold.ac.uk/3/fenn1.pdf

2.Ven. P. A. Payutto. Buddhist Economics - A Middle Way for the market place, translated by 3.Dhammavijaya and Bruce Evans, 1994, http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Academy/9280/econ.htm#Contents

4.Lily de Silva, 'Livelihood and Development', part of her One Foot in the World:http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/wheels/wheel337.html#dev

5.Mavis Fenn, Two Notions of Poverty in the Pali Canon, Journal of Buddhist Ethics, Vol.3 (1996), pp.98-125:http://jbe.gold.ac.uk/3/fenn1.pdf

1. Dhp. A.III.262-3 as cited in Payutto, 1994#

4. D.III.65-70; Walshe, 1987: 398-401

6. A.I.128 as cited in Payutto, 1994

8. D.III.183-4; Walshe, 1987: 462-3

9. D.III.189; Walshe, 1987:466

11. A.II.69as cited in Payutto, 1984

12. S.I.89-91as cited in Payutto, 1984

13. It.18as cited in Payutto, 1984

14. M. Fenn, Two notions of poverty in the Pali Canon, 1996:119.

15. M. Fenn, Two notions of poverty in the Pali Canon, 1996:118-9.

16. M. Fenn, Two notions of poverty in the Pali Canon, 1996:119.

17. Lily de Silva, One Foot in the world, 1986, http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/desilva/wheel337.html