Ven. Tian Wen at an alumni gathering in Hong Kong. From Ven. Tian Wen.

Ven. Tian Wen at an alumni gathering in Hong Kong. From Ven. Tian Wen. Ven. Tian Wen at a forum. From Ven. Tian Wen.

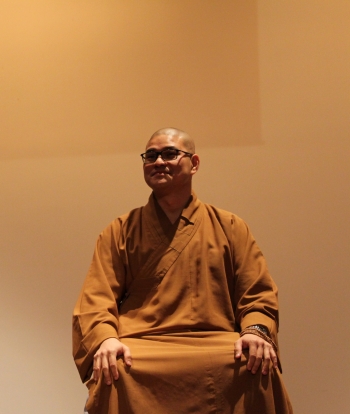

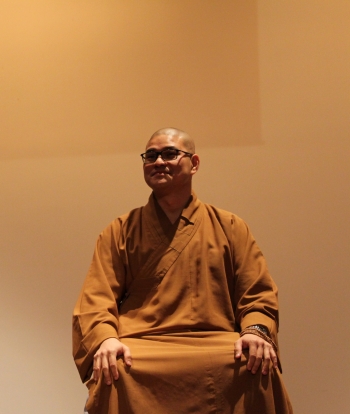

Ven. Tian Wen at a forum. From Ven. Tian Wen.The vision of Buddhism as a faith for the young and the living (rather than one needed only at death) has spread throughout the Sinophone world, radiating primarily from Taiwanese hubs like Fo Guang Shan, Fa Gu Shan, and Tzu Chi. No more were Buddhist monks to be seen as dour bald men for the funeral parlor. Nevertheless, Buddhism’s time-tested attentiveness to death remains a critical component of practice. And according to Venerable Tian Wen, it should not lose this identity: it is actually one of Buddhism’s most precious resources.

Based in Hong Kong, Ven. Tian Wen’s favored identity is as a simple Chinese Buddhist monk. But when his mother became terminally ill, the urge to find a way to care for the dying became personal. He has shared his ambitious ideas with me on many occasions, but it is only recently that he has been able to begin serious research into counseling for the deceased and bereaved. Having previously studied in Britain, he is now undertaking the Buddhist Ministry Initiative at Harvard Divinity School (which is sponsored by The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation), and travels extensively to learn about different types of therapeutic approach.

One important country in this respect is Taiwan, whose hospice care has been the subject of a paper by Jonathan Watts and Yoshiharu Tomatsu. In their article, Watts and Yoshiharu describe how Ven. Huimin’s work at the National Taiwan University Hospice and Palliative Care Unit is helping to define a “clinical Buddhism” for patients and carers (Watts and Yoshiharu 2012, 112).

“East Asia is a surprisingly vibrant sphere of palliative innovations,” says Ven. Tian Wen. “The first step in Hong Kong is to build on the growing network of healthcare professionals and monks who are willing to work with each other. We might need more meetings to set goals together and learn from each other to replicate the results we see in Taiwan.”

This type of palliative Buddhism involves six components: end-of-life suffering, death preparation, life meanings and affirmation, clinical practice of the Buddhadharma, fear of

death, and spiritual and life education. Summed up as clinical Buddhology, this school of healing embodies “the contemporary excellence of integrated medicine with the Buddha’s teachings for end-of-life care” (Watts and Yoshiharu 2012, 115).

Ven. Tian Wen was keen to emphasize the important distinction between learning from and simply copying wholesale the experience of Christian pastoral care. The East Asian view of the self is one of “physicality, mind, and spirit”—quite different to what Ven. Huimin sees as the occidental, Cartesian vision of mind-body dualism. This world view basically separates the person either into body or mind only, or into body, mind, and spirit, the latter leaving the body at death and moving on to a higher plane (Watts and Yoshiharu 2012, 115). Palliative care and counseling have long been a staple of Western Christian chaplaincy, and pastoral theology has been immensely influential in integrating religion and counseling. Neil Pembroke’s Renewing Pastoral Practice is a good example of how Christian counseling is rooted in Trinitarian thought: that is, a theology of relationship that explores the mysteries of love, death, and suffering in the framework of God’s self-revelation in Christ and the Spirit (Pembroke 2006, 8). But obviously, the Buddhist experience of clinical care cannot but be different.

Watts and Yoshiharu highlight Ven. Huimin’s general principle for an indigenous Buddhist care model, which is based on the Four Noble Truths: the first truth of counseling is that clinicians must tell the reality of the situation to patients. The second truth is that the patient, if her health continues to deteriorate, needs to be guided to accept death as part of life’s learning process. The third truth assures the patient and her family that suffering ends through achieving a tranquil mind, and changing one’s behavioral patterns through cultivating Buddha Nature and giving away possessions. The fourth truth is focused on the practice of Buddhadharma for attaining nirvana: a “good death” through the feeling of being guided towards liberation (Watts and Yoshiharu 2012, 116).

Such are the differences between the Christian model of care and the Buddhist vision that it is not surprising that “fragmentation” and “wholeness” form a consistent theme in Ven. Tian Wen’s thinking. He must grapple with an integration of disciplines not only from a religious angle, but also from a cultural perspective. “While some human experiences are universal—grieving, comfort, anxiety, fear—the cultural ways in which these experiences are dealt with are often different,” he says.

For Buddhists, Ven. Tian Wen suggests that counseling techniques must be adapted to East Asian cultural values, such as continuity, ancestry, and community. “For example, you can’t do East Asian tradition justice without looking at ancestor worship. Let’s try to engage with these traditional practices, and see how they may contribute to the grieving and healing process,” he suggests.

What does “pastoral” ancestor worship entail? Ven. Tian Wen argues that it is not about talking to the dead, but communication with the dying and departed at its most loving and tender. Ancestral worship teaches that the dead are still with us, and no matter their location, they remain receptive to our hopes, fears, and filial wishes. Framed thus, this traditional Chinese ritual suddenly becomes a lot less passé and unfashionable. It evolves into a way of relating to the dying and deceased that elevates the experience of the living onto a spiritual plane. The same approach, Ven. Tian Wen says, should be tried with the Qingming Festival. “Qingming is traditionally understood to be about paying respects to our ancestors’ spirits. But at its heart, it is about reunion. Who knows?” he speculates. “This traditional holiday might one day become a day for profound healing.”

The most basic necessity for all these initiatives, as with everything, is funding. Fortunately, these concerns remain a distance away for Ven. Tian Wen, who presses on with his objective of making pastoral Buddhism a mainstream practice in Hong Kong. “People are constantly being exposed to death, especially through all forms of the media,” he concludes. “But locally, how do we facilitate a changing of our common mindset of denying and avoiding death? Approaching death in a beneficial way: this is the best life lesson.”

References

Pembroke, Neil. 2006. Renewing Pastoral Practice: Trinitarian Perspectives on Pastoral Care and Counselling. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Watts, Jonathan S., and Yoshiharu Tomatsu. 2012. “The Development of Indigenous Hospice Care and Clinical Buddhism.” In Buddhist Care for the Dying and Bereaved, 111–30. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications.