Sun working in his studio

Sun working in his studio Calm workshop environment

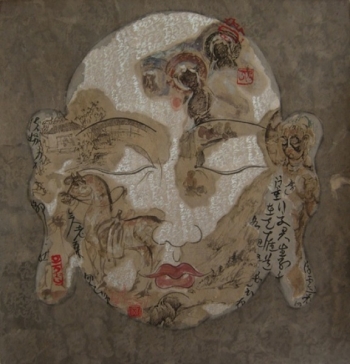

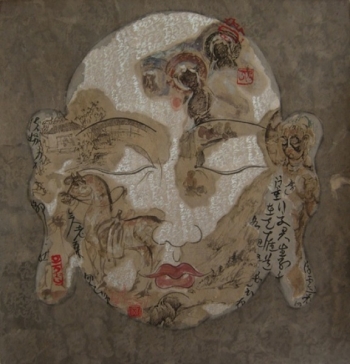

Calm workshop environment Blessings - Enlightenment series 1

Blessings - Enlightenment series 1 secular figures present in work

secular figures present in work darkness element in the work

darkness element in the work Sun Guangyi as a monk

Sun Guangyi as a monk monks receiving alms from village community

monks receiving alms from village community Mainland Chinese artist, Mr. Sun Guangyi, exhibits almost annually at the Sin Sin Fine Art Gallery in Hong Kong. Over the years, a very special relationship has developed between the artist and the owner of this gallery. Journalist Emma Bi went to review his work at an exhibition earlier this year and report for Buddhistdoor International (BDI) on this interesting artist who is inspired by Buddhism in a very personal and meaningful way in his creative process.

Emma shares with you her dialogue and discoveries with artist Sun Guangyi in order to appreciate this special story of an intersection between art and Buddhism:

Emma Bi: This year you produced a series of paintings entitled “Blessings - Enlightenment” for Sin Sin Fine Art Gallery. Could you please share with us a little bit about the background of this series and describe your working process back home in China?

Sun Guangyi: In 2005, I was invited to attend an exhibition in Munich, Germany. There I cooperated with a German artist named Mr. Plahl to finish and exhibit a piece of work called “The Road to Shangri-La”. After that, I began the process to make the Blessings series, which has continued for several years.

This overall series, “Blessings”, has been worked on both in my home in Yunnan Province and also Beijing, China. I have exhibited stages of the series on three different occasions in HK. From 1994 until now, my various workplaces have been moving, and this seems to be reflected in the fact that my pieces have changed together with my workplace. I don’t know how to express exactly what my workplace environment looks like, but I do remember the comments of some German friends who visited my workplace in the Beijing Art District: “they said that they liked the space because it was elegant and comfortable”. Actually my workplace is simple; the pieces are mainly ink-and-color; and the air is freshened with the sandalwood fragrance. For me, it is like a room for meditation.

My timing is flexible fortunately because the creation process is complex in that I need to make a structure, prepare the paper to look older, and then paint. These steps take a lot of time in order to achieve the best result. Depending on size, the pieces can take two weeks to three months to complete.

EB: In reviewing your work, could you share with us some comments about the content of the recent “Blessings – Enlightenment” exhibition? Where do all of the images come from… your life experience… actual locations… what is your inspiration?

SG: The Blessings series inspiration originally came from my travel experiences in Tibet when I saw the Mani Stones everywhere and reading the Avalokitesvara Sutra. In the history of Tibetan Buddhism, there are a lot of sravaka (devoted people who practice Buddhism) who spend their lives carving the Mani Stone as a form of prayer, and reciting the “Om Mani Padme Hum” mantra. The Blessings series has traced the writing of Tibetan characters for “Om Mani Padme Hum” since 2005. Some simple characters were added, but most of the ideas came from the Buddha’s statues and ancient cave paintings.

The six-syllabled “Om Mani Padme Hum” is written in every piece of the Blessings series over the years: in some it is in the background… in others in the portraits. From the perspective of art, this is the continuous thread and underlying motif in this series. From the perspective of philosophy, I draw inspiration from the Avatamsaka Sutra which indicates that recitation of the “Om Mani Padme Hum” mantra can be an expedient means for the practitioner to break the cycles of samsaric existence.

The black coloration and darkness in my paintings symbolically represent different types of suffering in life.

EB: In some of your paintings there are figures that appear to portray secular life: children, vendors, farmers, animals, houses, bridges – also in those works are images of Buddha, monks, the western Pure Land, musical instruments, and monasteries. Are you trying to demonstrate a balance between the secular life and the religious world?

SG: No, it is not about the balance between secular and religious lives… for me, Buddhism is about a kind of perfect equality between all of the elements.

The Buddhas with high spiritual attainments were all originally ordinary people in secular lives such as children, vendors, woodcutters, farmers, and monks to name a few.

There are bodhisattvas (advanced beings who come back to help all sentient beings in this life) who return again into ordinary secular lives and choose to live amongst those who need guidance. They will manifest in forms such as children, vendors, woodcutters, farmers, and monks to name a few.

The point I try to make is that ordinary people can achieve spiritual advancement, and those spiritually advanced can return as ordinary beings. In this sense, all things are equal.

This is what I intend in presenting these images.

The Dharma has never left the secular world.

EB: We understand that in your personal life, you once chose to be a part-time monk. Can you share with us some of the reasons why, and reflection on your experience?

SG: Why I wanted to be a temporary monk? Firstly, I wanted to experience the monk’s life. Secondly, I wanted to learn the scriptures, principles and laws about Buddhism. There are certain rules for the monks called vinaya codes, which are not accessible for lay people to read. In order to be able to learn from these principles, then my best method of access was to become a temporary monk. The Buddha stated so many merits of leading a contemplative life. In Nepal, a great Rinpoche used to tell my teacher that, “Even one day’s simple and clean monk life can have a great rewarding.”

In the countries that practice the tradition of Theravada Buddhism, a man has to take the monk vows for at least 7 days once in his lifetime. Some choose to be a monk for their whole life. But, in mainland China, it is not the custom to take temporary vows in the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism. However, in the Mount Jizu area of southwestern China, there is a Theravada temple with a monk named Shou Fang Guang who allows lay community men to take temporary vows and experience Buddhism in the life of a monk.

In my experience, whether it was the monastic life in the temple, or the actual very long walk to get there across two prefectures through mountainous terrain – it was all-together the most precious treasure experience in my life.

My reflection is that there are two approaches to Buddhism: one is about academic study and research – more scholarly. The other approach is through actual practice of the teachings and meditation. Buddhism has to be practiced, deeply practiced, to go on with the progress of theories.

My teacher used to tell me that, ‘just be like a soldier in the army; imagination about the soldier’s life is different from the real soldier’s life’.

EB: Please share with us a little bit about your daily life as a monk?

SG: In 2007, during a novitiate program at the Hua Shou Fang Guang temple in Yunnan province, the times to wake up, eat, and sleep were very strict. On a different occasion at the Man Ting Fo in Xi Shuang Ban Na in southwest China, we all had a little small room. We woke at 5 o’clock every morning, did sitting & walking meditations, and chanting. After breakfast, we walked barefoot to the village with our bowls and collected alms exactly as the Buddha would have lived in earlier times.

During morning hours, we did more walking & sitting meditations, and cleaned the rooms. After lunch, we repeated the meditation routines. As per the Theravada custom, we did not eat again after noontime. Evenings were spent on chanting and meditations. Bed-time was the only moment of the day of our own choosing.

Sometimes, we went on short pilgrimages to nearby holy places.

The first time I went out to ask for food with a bowl, an image from a story in the Diamond Sutra came to mind: the prosperous city, the great image of the Buddha collecting alms was all there… “At that time Buddha entered Sravasti with a bowl in his hand to ask for food. After he received the food he returned, ate the food. Later he put the bowl away, washed his feet and arranged his seat, and sat down.”

I had the luck to experience the life of Buddha when he asked for food.

One time when an elderly grandmother kneeled down beside the road to us and offered the breakfast, which was just made, with flowers and candles - I, a so-called civilized person who received a modern education was deeply moved and impressed. My tears shed onto the bowl, my brothers wept heavily too. We were all touched deep inside ourselves by the great sanctity from the woman. Compared to my life as a layperson when I studied Buddhism at home, I finally understood the purpose of a monk’s life in the world and the meaning of gratitude. That particular scene still appears in my memories often.

The short period of that temporary monk’s life lasted for one month. Near the end, some monks volunteered to walk together from Xi Shuang Ban Na (the city where the temple was located) to Mount Jizu. Eight of us made the journey of 800 kilometers by walking where we slept in the wild, in riverbeds, in forests, and in abandoned houses with only three sets of robes and a bowl. It took us 25 days in total. Needless to say, it was an unforgettable experience.

Based on all these special experiences, I hope to take some time each year for retreat from my layperson life.

EB: What comes to your mind when you are doing meditation? Do you use these mental images in your artwork?

SG: The meditation experiences are different each time. In general, I feel the illusory images are the reflections of our hearts. To put it simply, the feelings are like dirty water. The sediment in the water will start to settle down after one has calmed in the meditation process. When there is calm, you can see your heart more clearly.

“The heart is like a painter that can craft the whole world” <Avatamsaka Sutra>

With this inspiration, I paint from my heart.

EB: Which poetry in Buddhism do you like best and apply to your work as an artist?

SG: My favorite poetry is by Zen Master Wumen from Song Dynasty (???N????)

“?K???ʪ?????A?L?????V?????F?Y???ƬE????A?K?O?H??n???C”

Flowers in spring, moon in the autumn

Breezes in summer and snow in winter.

If there are no secular worries in your heart,

That is the best season in the world.

Emma Bi: Thanks so much for answering all of these questions. We are really thankful for the opportunity to learn something about your background and how Buddhism influences your creative process that we can all share and enjoy.

Additional Reference:

http://www.sinsinfineart.com/artists/Contemporary/SunGuangyi/page1/

http://www.sinsinfineart.com/about/about/page1/