Earlier this year, I was privileged to attend the first conference of the Buddhist Ministry Initiative at Harvard Divinity School (HDS) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The three-day event was titled “Education and Buddhist Ministry: Whither—and Why?” and was organized as a “working conference,” with a focus on building conversation partners, mapping the landscape of Buddhist ministry, and exploring opportunities for collaboration.

The Buddhist Ministry Initiative, founded with the support of The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, trains future Buddhist religious professionals to enter fields such as hospital or university chaplaincy and social work. Students can also learn Pali and attain knowledge in specific Buddhist scriptures.

The 23–25 April conference was comprised of an invited audience of HDS faculty, students, and international guests. It brought together representatives of institutions and programs that educate students aiming to become chaplains and caregivers, leaders in Buddhist communities and organizations, and members of groups and movements working to apply the insights of Buddhist practice and thought to address suffering in the world.

Professor Charles Hallisey, Yehan Numata Senior Lecturer on Buddhist Literatures at HDS, opened the conference by invoking the Buddhist Jataka tales (stories of the previous incarnations of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni) on the subject of friendship.

“In terms of friendship we can learn from the Buddhist Jatakas. . . . All kinds of animals that are not at all supposed to be friends with each other are always making friends with each other. People are always suspicious of that. The monkey and Mr. Crocodile [are] friends; Mrs. Crocodile says I know you are not friends with some monkey, there’s another lady crocodile somewhere—that is what they have to be suspicious about, [and in the same way,] we can be suspicious about different institutions making friends.”

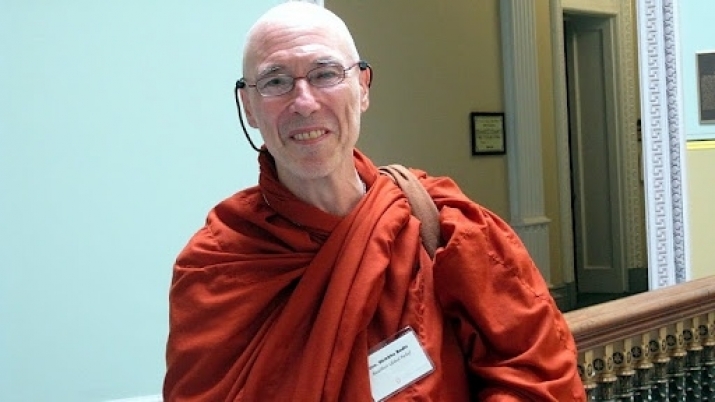

Prof. Charles Hallisey, left. From Harvard Divinity School

Prof. Charles Hallisey, left. From Harvard Divinity SchoolProfessor Hallisey drew a comparison with ostensibly discordant institutions that, while once in opposition to one other, were able to forge an institutional friendship, expressing hope that similar harmony could be achieved at the conference. Based on my own participation in the three days of panels, workshops, discussions, and meditation sessions, I believe that this aim was realized.

One participant pertinently questioned the value of institutionalizing the Dharma. Professor Hallisey responded that the conference did not approach the subject from the perspective of the individual; rather, it aimed to examine what could be possible from the perspective of institutions, which “. . . allow us to do things that go beyond our own lives, and go into the future; they are ways in which humans band together to give gifts to the future.”

With the Buddhist Ministry Initiative now in its fourth year, this first such conference brought together bhikkhus (monks), bhikkhunis (nuns), Buddhist scholars, academics, and chaplains from all over the world, providing a platform for participants to work towards a future that could be both pragmatic and visionary.

Many of the discussions centered on drawing up a standard Buddhist ministry curriculum at HDS that would enable students to become scholars and academics, or chaplains working to bring the wisdom of the Buddha’s teachings to the general population. Drawing on the wealth of experience among the participants, who represented a diverse range of monasteries, nunneries, colleges, and Buddhist non-profit organizations, the panels were able to work towards defining the best practices to be incorporated into the curriculum.

Judith Simmer-Brown, a professor of Religious Studies at Naropa University in Colorado, for example, recommended that meditation practice be included in the curriculum to encourage students to actively practice Buddhism along with academic study. Naturally, with many different schools and lineages of Buddhism, each with their own particular meditation practices, the issue became a question of how to select an appropriate and standardized meditation approach for the curriculum.

What emerged was the realization that such variations also serve to highlight the beauty of the breadth of the Dharma—an organic expansion, perhaps, of Buddhism over many millennia, like a tree with many branches. While no specific method was settled upon during the conference, many suggestions were recorded for future consideration.

Professor Beatrice Chrystall, a lecturer in Pali at HDS, expressed gratitude that the conference had provided many individual groups that had been previously working in isolation with an opportunity to gather and work for shared concerns. In addition, due in part to the Buddhist Ministry Initiative, the study of Pali at HDS is officially in its first year, and for the first time Pali is now part of the HDS Summer Language Program, in addition to being offered during the regular school year.

Another important issue raised at the conference was how to engage the Buddhist community at Harvard with other Buddhist communities around the world. Venerable Upali Sraman, a third-year student of Buddhist Ministry at HDS and an incoming co-president of the student-led Harvard Buddhist Community, noted that one of the main efforts next year would be to reach out to Buddhist temples and centers in the Boston area for the purpose of collaboration.

Venerable Bhikkhu Bodhi, founder of Buddhist Global Relief (an interdenominational community of Buddhists and supporters helping people afflicted by poverty, natural disaster, and societal neglect), shared the history of his NGO, which sprang from his desire to serve the people of Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the 2004 South Asian tsunami. Having spent more than two decades in Sri Lanka as of 2004, Bhikkhu Bodhi said that he had felt a deep gratitude to the people of the country, so set about fundraising among friends and supporters. A total of US$160,000 was collected, which he was able to disburse among organizations in Sri Lanka engaged in relief work. Today Buddhist Global Relief is active in 14 countries.

We were soon to realize that the Buddhist Ministry Initiative at Harvard represented a similar opportunity to respond to suffering. By a tragic coincidence, the first devastating Nepal earthquake struck on the last day, and we were distraught at the extent of the loss of life and destruction. Professor Hallisey initiated a prayer session and invited members of the audience to offer prayers and chants, further cementing the common purpose of the conference. Attendees rallied to coordinate their online communities to strategize relief work with existing global Buddhist outreach efforts, and discussed plans to expand such activity.

Despite the shadow of tragedy, as a Harvard Divinity School graduate I was heartened by the positive outpouring of energy, enthusiasm, intentionality, and commitment to Buddhism shown at the conference. There is no doubt in my mind that the gathering has catalyzed and galvanized all participants for the future.

This first conference can be viewed as an experiment in bringing together a broad diversity of Buddhist voices, experiences, understandings, perspectives, and ideas that could have yielded any number of results. Remarkably, what arose after the three days was a strong bond and sense of metta among the HDS community and the invited guests. Professor Janet Gyatso, Hershey Professor of Buddhist Studies at HDS, made an insightful observation on this phenomenon: “Is it Buddhism? I think it is Buddhism.”

Harsha Menon is an artist, film-maker, and writer based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her work has screened at the Sundance Film Festival and the Venice Biennale. She is an advisory board member of the Buddhist charity, Dongyu Gatsal Ling Initiatives.

See more