With the 20th Century often characterized by poets and essayists as an era of lost innocence, many in the 21st Century have had the fortune (and this is truly a fortune) to understand that black and white or pure right and pure wrong is a very rare dichotomy in morality. There are shades of grey across the entire spectrum of ethics. These grey areas are something that the fundamentalist is unable to accept, because, Heaven forbid, that there exist dilemmas and difficult decisions to be made. Some may argue that religions, with their precepts and commandments and vows toward right view and action, are in a poor position to preach about grey areas. To debate the bioethics of assisted suicide, for example, would seem to be clearly off-limits to any religion that commands, “Thou shalt not kill.”

To take life is a violation of the most basic vow a simple layman can take. But even an everyday household situation – for example, a cockroach infestation threatening to overrun and contaminate the home or monastery – demands that we look further for simply “Don’t kill.” Of course, given that the hopeful vision of Buddhism demands a great faith in the potential of the sentient being – that is, the innate capacity of every being to become perfectly enlightened and a Buddha – it is no wonder that it has developed the idea of wrongdoing that can be stained by defilement (a mar on our spiritual practice and bodhisattva progress which must be confessed and repented), and the less serious occasion of wrongdoing without defilement. This is one of the foundational strategies by which the Mah?y?na tradition has attempted to address moral grey areas. They are all the more relevant in today’s increasingly complex ethical arena of gender equality, LGBT rights, environment and ecology, racism, discrimination, et cetera.

The resolution to benefit all beings and become enlightened also becomes the benchmark by which we see if our wrongdoing also defiles our spiritual practice. Mental aptitude or improbity (citt?patti) is recognized as a source and manifestation of moral infringement in the Mah?y?na. In the Bodhisattvabhumi, we are taught that the gravity of moral transgressions depends, as in theVinaya code, on the circumstances in which they were committed (Wogihara, 160.1 – 165.1). Sins that are committed out of states of mind antithetical to the bodhisattva’s resolution to become enlightened for the benefit of all beings constitute transgressions stained with defilement. These states of mind are: indolence, irreverence, greed, sensual desire, pride, negligence or animosity, which are diametrically opposed to compassion, goodwill, et cetera. However, if developed out of forgetfulness, illness, mental distraught or ignorance, the fault is a transgression without defilement (Wogihara, 180.10 – 12). These can be said to be less “mentally corrupting” than states such as pride or irreverence.

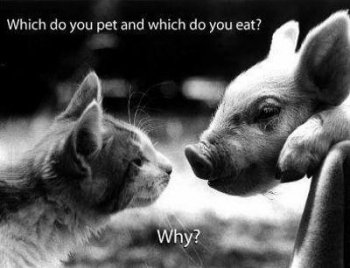

In the Mah?y?na, of course, anything committed out of hatred and egoism would constitute a true wrongdoing with defilement. They even overtake sensual desire as the most destructive threats to moral purification. Hatred and egoism are not only irreconcilable with compassion, but they are recognized as the strongest forces that erode altruistic tendencies in the Buddhist disciple, including the Four Divine Abodes (brahmavih?ra). Transgression, therefore, is not always or necessarily an infringement on a set code of ethics, precepts or commandments, but through the omission, neglect, or violation of actions that would promote the spiritual welfare of sentient beings (Pagel, 1995, 180). There is therefore an incredible difference between the difficult decision to put down a suffering animal that can’t be saved and the choice of shooting one on a hunting trip. Both decisions are wrongdoings, as they both involve life-taking, but the former action is absent of any significant defilement.

The promise of total altruism for the sake of all beings means that, as Buddhists, we have some form of positive emotional disposition towards them. Attachment and desire are not ideal, but the Madhayamak?vat?ra states that whichever the degree or circumstances of desire, for the bodhisattva it is always preferable to hatred (de la Vallé Poussin, 51.3 – 19). Hatred is capable of instilling such contempt in the bodhisattva that she might choose to abandon her undertaking altogether (Pagel, 1995, 172 – 3), whereas the other negative mental states do not necessarily prompt a destructive state of mind directed against other beings. And finally, if a Buddhist commits wrongdoing that conversely originates in the bodhisattva’s resolution (the slippery notion of up?ya or skillful means), it is portrayed as entirely free from fault or blame. For those who are ill-equipped in skillful means and act out of weakness or attachment, the deed remains a fault, albeit only a slight one.

These spheres of wrongdoing (and in the case of skilful means, wrongdoing in name only) help us to understand how the Mah?y?na sees hatred and egoism. Are we able to accept that we have done wrong while not being defiled? This may have been the case for many of the difficult choices we were forced to make in our lives, from domestic infestations that only a Buddhist or Jain would agonize over, to much more serious ones involving cloning, euthanasia, prisons and the death penalty, and many more. Of course, I propose that this is only a starting point for the Buddhist discussion. Endless questions can be asked: how can we know our inner heart has not been defiled by a wrongdoing? Do we have the right to be confident in any situation? And if we do not even know we have done something wrong, when can we know we have backtracked? These are questions that will need the assistance of ethicists and moral philosophers.

Perhaps it is simply best to play it safe, and repent and express our genuine regret before the Buddhas whenever we feel that twinge, twist, warp of conscience inside us.