Last week, leaders from the Group of Seven (G7) nations met in Cornwall, England. As usual, the meeting involved a great deal of pomp, circumstance, and at times awkward formalities. It also signaled to the world the priorities that these leaders wished to set forth in the years to come. Perhaps most important at the meeting, however, was the opportunity for friendships to arise and strengthen. At a time when the world is more polarized than it has been in decades while facing enormous common challenges, friendliness and friendship are increasingly essential, especially among our nation’s leaders.

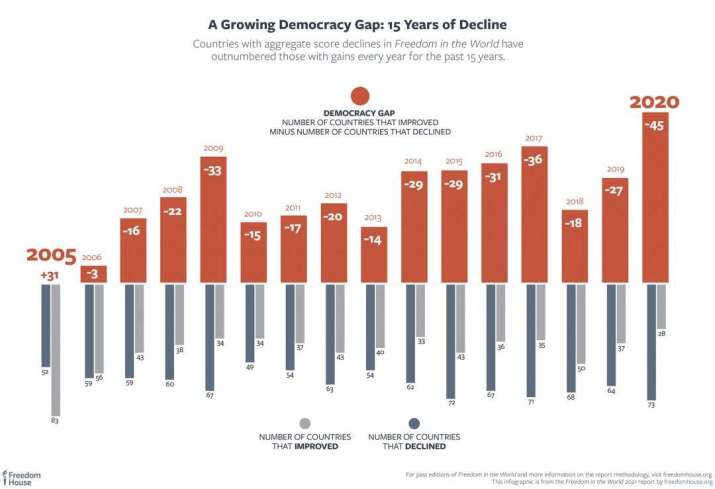

Even if we set aside the COVID-19 pandemic and the worsening effects of the climate crisis, it is apparent that humanity is fragmenting in ways that could clearly give rise to violence and other forms of suffering. Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz of Freedom House, a global NGO studying the ebbs and flows of human freedoms across the world, warned earlier this year: “As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favor of tyranny.” (Freedom House)

According to their analysis, 2020 was the worst year in recent history as countries across the world faced major threats to public freedoms. They documented the arrests of journalists and government critics in several nations, the lengthy campaign to discredit US presidential elections, the scapegoating and targeting of religious minorities, and increasing secrecy by governments that are called to be open to the people. In March, in his first major foreign policy speech as America’s top diplomat, Antony Blinken described the report as “sobering.” (Business Standard)

One of the 20th century’s greatest thinkers on authoritarianism, Karl Popper (1902–94), warned of many of the tactics and effects of authoritarianism. Charles Edel, a senior fellow at the United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney, drew from Popper’s wisdom in 2018 as he watched the rise of several authoritarian thugs and strongmen across the world—“enemies of the open society,” as Popper would call them. He quoted Popper, who wrote: “The authoritarian will in general select those who obey, who believe, who respond to his influence. But in doing so, he is bound to select mediocrities. For he excludes those who revolt, who doubt, who dare to resist his influence.” (The Open Society and Its Enemies, p.147) Edel also notes that:

. . . Popper argued that history was a long-term battle between proponents of open dynamic societies and authoritarians who benefited from closed societies. He warned that the enemies of open societies were powerful and numerous, and cautioned that liberal democracies were rare, fragile and required extreme vigilance to maintain.

His message is once again relevant. Around the world, strongmen have staged a comeback. Hungary, Turkey and Venezuela continue their slide into authoritarian rule. Democratic norms have eroded in the Philippines and Poland. Myanmar, which had slowly began opening its system, has now executed an ethnic cleansing and jailed journalists covering it. Right-wing populists have gained traction throughout Western Europe. (The Washington Post)

In a less-worrying yet still urgent plea, Peter Hershock, director of the Asian Studies Development Program at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, writes: “. . . globally deepening interdependence has been meaning greater inequity and manifestly less-sustainable practices across a wide range of sectors—from the social and economic to the political and cultural—both within and among societies.” (Hershock, p.1)

Hershock warns that our modes of thinking are no longer adapted to the fast-paced, information-rich, and deeply interconnected world in which we live. We can see this in so many ways today: from extreme depression in our youth to waves of ultra-nationalism and xenophobia occurring primarily among older generations. As the world continues to open up, fear and ignorance have snapped back against it in countless ways, small and large, around the world.

Hershock’s response to this is to urge us to develop greater clarity about our values. We need to deeply see our interconnectedness and the ways that this can lead to suffering or greater peace. Next, we need to develop our focus to see the relevant situations that we must respond to in order to help liberate ourselves and others. He warns that in our current age, a major impediment to responding effectively is the excess of information we are faced with each day. The theorist Herbert Simon recognized this 0 years ago:

In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it. (1971, pp. 40–41)

Buddhistdoor Global columnist Ernest Ng offers wisdom for cultivating a healthy personal approach to social media in order to develop true friendships. When we approach social media with the perspective of even the most ancient of Buddhist teachings on friendship, the application becomes clear. As Ng writes:

. . . [the] teachings from the Buddha set quite high standards for spiritual friends. He invites us to reflect deeply on whether we have spent enough time and effort cultivating true friendship, which could be genuinely beneficial and nourishing to our lives and spiritual journeys, or are we spending too much screen time with foes in friendly guise?*

Returning to the summit of national leaders, we might ask who among them has shown genuine interest in nourishing the lives and journeys of citizens of the world? And who seems to be there only for personal or national gain? Personalities and even most policies aside, a spirit of global friendship is needed as we continue to battle the twin enemies of the coronavirus pandemic and the climate crisis. Worth noting is who was and so often is left out: poorer nations.

While US President Biden pledged 500 million vaccine doses to poorer nations and fellow G7 leaders matched it to total 1 billion doses, such pledges come only after the wealthy countries have secured an excess of vaccines for their own citizens. The move thus signals an awareness of a need for global sharing, but hardly a firm commitment.

If Hershock is correct, then as Buddhists we can still see our various practices as leading toward greater global friendship and peace. Our meditation, our chanting, our dedications of merit all present us with an opportunity to see beyond national borders, to reach out—metaphorically or literally—to those suffering around us. With this we can help build a more free and open public sphere, allowing the naturally unfolding interdependence to foster growth and peace rather than division and discord.