From "Elephant Journal"

From "Elephant Journal" From the European Institute of Applied Buddhism

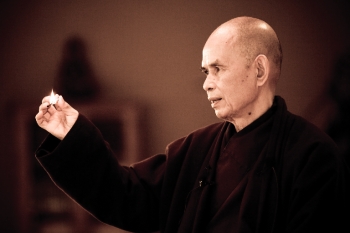

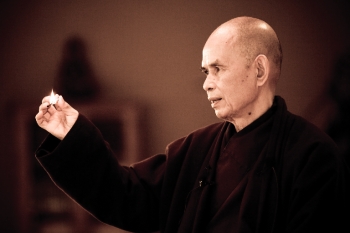

From the European Institute of Applied BuddhismOn 12 November, Thich Nhat Hanh (or Thay) suffered a severe brain hemorrhage that put him in hospital. As the global Buddhist community continues to keep close watch on the world’s most famous Zen master, the most recent Plum Village press release on 30 November states that his condition remains stable—the latest scan shows that his hemorrhage has slightly lessened, and that the edema, while still present, “has not worsened.” The doctors and neurologists by his bedside now face the challenge of moving into medium-term relief.

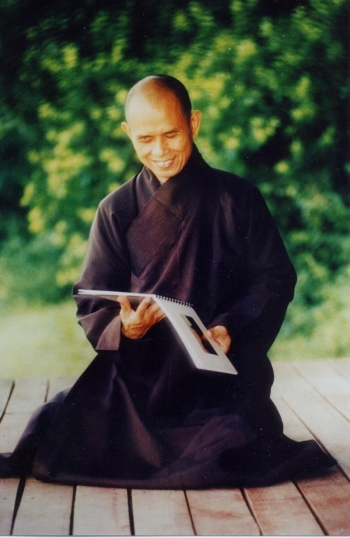

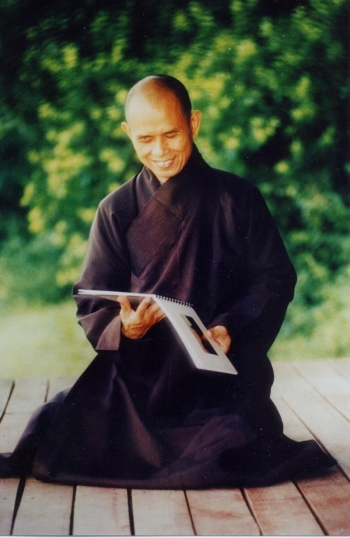

Thay has become ever frailer over the years. The last time a member of our editorial staff saw him was in Thailand in 2013, at a retreat at Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University. His voice, already so gentle and tender, had become even softer, and he needed to move very slowly. Yet, his teachings are more influential now than ever. His position as a monk who established a form of “Western Buddhism” that felt palatable to native European and American audiences remains firm. Centuries from now, he may well be remembered as a monk whose role in transmitting Buddhism to different regions of the world and successfully adapting it to local needs was as important as that of the Central Asian and Indian translators and their Chinese collaborators in imperial China.

Thay’s contribution to shaping the identity of Western Buddhism has been at both the philosophical and pastoral level (and he has therefore found many allies in the West, from academic to monastic). His voluminous output of poetry, essays, studies, and even fiction articulates an egalitarian vision of mindfulness that can be embraced by every demographic, from children to non-Buddhists. His philosophy

of Engaged Buddhism, a movement mirrored by other forms of applied Buddhism in Sri Lanka (Sarvodaya) and East Asia (Humanistic Buddhism), has become the subject of academic writing in Buddhist Studies. Ethicists cannot articulate modern Buddhist morality without standing on his broad shoulders.

From the pastoral perspective, his retreats around the world, his Order of Interbeing (interbeing is another term he coined), and Wake Up movement have been critical. They have transformed individual lives and communities through reconciliation, often in ways sometimes assumed unachievable in Buddhism. He showed the world that Buddhism could be deeply involved in society whilst remaining non-attached.

The socio-economic, political, and environmental challenges facing the next generation of Buddhists are vastly different to Thay’s experience. Yet, he acutely understood the shifting landscape of ethical and moral crises in the world. In his books over the past several years, he has written of ecological devastation as the perennial concern of the 21st century. Stronger ecological language can be observed in his newer publications. In the second of his Five Mindfulness Trainings (his expanded version of the Five Precepts), he specifically mentions global warming: prevention and mitigation of global warming is our duty to future generations, and a refusal to fulfill it is to commit theft against our children’s future—a deeply unskilful violation of the precept of no stealing.

This shift in focus from social justice to environmentalism is not a coincidence. To see why, we should look back at his intellectual tenure. Thay’s presence in Western Buddhism stretches from the 1960s, when he traveled all over the world to end the Vietnam War (he went into exile in France in 1973), to the present day. He now invokes Mother Earth as a counterpart to the Mahayana divinities, a mindful being that needs us to heal the damage we have inflicted on her. The context is significant: the eco-Buddhist movement has matured greatly since the 1990s, when Joanna Macy outlined a well-intentioned but theologically shaky interpretation of Dependent Origination as a call to environmental awareness. Thay’s orientation is much more grounded in Mahayana panentheism. He was also a key contributor to the landmark publication A Buddhist Response to the Climate Emergency (2009), which set in motion the petition “A Buddhist Declaration on Climate Change.”

Also notable has been his extraordinary interfaith openness, which has been celebrated by religious leaders around the world since Martin Luther King, Jr. His particularly deep friendship with the Catholic Church continues to this day. This December, he was hoping to go to the Vatican at Pope Francis’s invitation to support a global initiative to end modern slavery, evidencing his mindfulness of the changing world and the moral priorities that call Buddhists to speak out and act. Now, the Vatican must make do with a delegation of 22 monks and nuns, including his closest student Sister Chan Khong and Thay Phap An, director of the Plum Village-affiliated European Institute of Applied Buddhism in Germany.

Plum Village is hopefully finding ways to creatively build on Thay’s immense philosophical bequest: the greatest danger to a movement as vibrant and adaptable as Engaged Buddhism is being paralyzed by its founder’s legacy. For the sake of both those inside and outside their communities, Plum Village has probably begun to envision what a world without its founder would look like. A spiritual, intellectual, and pastoral titan of Western Buddhism, the last few decades have been nothing less than the era of Thich Nhat Hanh—in Thomas Merton’s words, “the Zen monk who sees beyond life and death.”

For further information, see:

Thich Nhat Hanh Recovering from Brain Hemorrhage (Buddhist News)