In the West, comparative religious studies is a way of widening a person’s intellectual and spiritual horizons for reaching a greater understanding of global culture. This apparently has been made possible due to a secularist approach that is widespread in modern Europe where traditional religion has been on the decline over the past 30 years. According to the religion correspondent of the London Daily Telegraph“Britain’s Churches will be well on the way to extinction by 2040 with just two percent of the population attending Sunday services”

(Awake)

In North America’s liberal Protestant society non-Asian Buddhists share the same liberal values. Religious differences there do not lead to social friction or mutual suspicion. In other words nowhere in the West is Buddhism an ethnic religion. Consequently Westerners do not understand Buddhism the same way that ethnic Buddhists do.

In the East, especially in Asia inter-religious dialogue has become a complex issue, although constitutionally some Asian countries like India are secular. This complexity is not always necessarily due to differences in beliefs but the way it is often interpreted – sometimes with very good reason.

The background to this is the strong bonds that communities and ethnic groups in the East - even in parts of Eastern Europe - have formed with ancestral religions. This sensitivity is reflected not only between different religious groups but also between different schools of the same religion. Here the most number of examples are found in Christianity. The Christian evangelical movement in Latin America is divided up into innumerable separate churches.

In countries like Sri Lanka where the large majority has identified itself with Theravada Buddhism (although influenced by some Mahayana traditions over the centuries) when attempts are made to introduce in the name of Buddhism alien rituals and symbols hitherto unknown to the majority of locals it invariably leads to needless problems. This is a small wonder since the actual motives behind such attempts have little or nothing to do with making Theravadins understand the different schools of Buddhism.

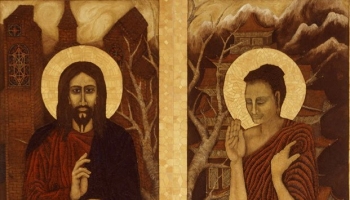

Coming to Christianity, Tibet’s Buddhist monks first heard about the one God, Salvation, Eternal Life, Resurrection and the like when Western Missionaries went there. The monks concluded that Christ’s teachings were similar to that of the Buddha.

Unlike Christianity, Buddhism did not emerge as a religion of the oppressed although in his day the Buddha was often highly critical of the elite in India’s caste-ridden society. It helped to form a protest movement against exploitation of religion and the corruption of Brahmin priests. In that sense Buddhism was a social movement from the beginning. However Buddhism advocates compromising positions and does not find itself fighting on the side of the poor against the rich. Buddhism’s tendency has always been to compromise between classes. In Theravada Buddhist countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand the Sangha were the mediators between the ruler and the ruled. They were also advisors to the kings.

In Christianity both the theologies of domination and liberation have always existed side by side. Although Christianity began as a religion of the oppressed it afterwards became a religion of domination. (Christian Worker 4th Quarter 1987)

As Sulak Sivaraksa, founder of the Thai Inter-Religious Commission for Development said nearly 20 years ago, Buddhism’s strength and weakness are that it tends to find similarity with other religions. Hence it finds no difficulty to co-exist with Hinduism, Daosim, Animism and Shintoism. Buddhism does not claim that it is the one and only way to end suffering.

As for Hinduism it encompasses traditions raging from atheism to pantheism and just about everything between them. However, this plurality of traditions does not symbolize any internal contradictions or inconsistency. A true Hindu knows that his own path, whether it is that of Bhakti, Karma, Gyana or Raja Yoga is but one of many that lead to the same truth.

Some monotheists seem to be in collision course with Buddhists and other religionists although it need not be so at all. The problem often arises when attempts are made to ‘market’ religions by dubious and unethical means. We saw the likes of this in Sri Lanka in the aftermath of the tsunami of December 2004.

This kind of approach to human problems is continuing to cause religious tension in such Asian countries as India, Sri Lanka and South Korea. The call for a ban on unethical conversions by both Buddhists and Hindus is strongly linked to such unwarranted intrusions.

Although Islam is a monotheistic religion, there have been less friction between Muslims and Buddhists in Sri Lanka compared to the problems that have occurred between the latter and some Christians for well over a century. One reason perhaps was that the Christian Church enjoyed the patronage of colonial rulers.

In Sri Lanka when Christianity was introduced during the European rule some Buddhist monks regarded Jesus Christ as a kind of Bodhisatva, which in essence is correct. But this Buddhist view was not acceptable to the white Christian missionaries. Their attitude is clearly reflected in the writings of the American founder of the Buddhist Theosophical Society, Colonel Henry Steele Olcott (1832-1907).

The situation was the same in Tibet where the foreign missionaries found it difficult to admit that Buddhism also could be a true religion. These negative attitudes not surprisingly caused mutual suspicion and sowed the seeds of friction. In contrast the Hindus, Shintoists Confucians, Daoists and the like find it far less difficult to co-exist with Buddhists.

Buddhism has always been flexible in adapting to indigenous cultures. For instance a foreigner visiting Japan will find it almost impossible to see from the outside the difference between a Shinto temple and a Buddhist temple.

The Gospel values that Christ preached and practiced forms the basis of a simple culture much closer to Buddhist culture, though there may be certain differences. We have to note that a religious doctrine cannot be taken in isolation without the culture that emanates from it. This needs to be understood well in drawing comparisons between different religions and building communal harmony - best reflected in mixed religious marriages. Here I can cite a personal experience. The parents of my son-in-law are believers of two different religions. The father is a Catholic and mother is a Buddhist. Two of their sons are Catholics and one is a Buddhist. But all three sons observe the Sinhala Buddhist custom of worshipping parents and when required attending sutra (parittta) chanting events.

According to Mahayana Buddhist tradition if a person who, as a Bodhisattva, rids society of a persistent menace even going to the extent of exterminating human beings he will go to hell for his sins. But he undergoes such suffering for the love of his fellow beings. This is something quite like the Christian concept of vicarious suffering.

Today more Christians have taken to vegetarianism which was hitherto largely limited to Hindus, Jains and some Buddhists. Animal welfare has drawn the increasing attention of many Christians and it is one area that they can form strong bonds with Buddhists and Hindus.

You can access the original Bodhi Journal articles in our archive.

You can access the original Bodhi Journal articles in our archive.