These days, it is almost impossible not to associate culture and sophistication, such as refined tastes in music, literature, sculpture or fine dining with “creativity.” One needs to contribute something original, something that no one else has thought of before, so that connoisseurs and aficionados of something like contemporary Tibetan art or Chinese calligraphic painting can point to a piece of work and applaud its creator. We call her “creative,” someone who has created meaning as opposed to having discovered it. Yet I would ask: is meaning something that can only be created? Or can it also be discovered creatively?

We may sing similar praises for great religious philosophers who have contributed invaluable insights to the human condition, to flourishing and culture. Strictly speaking, the Buddha was immensely creative as a thinker and philosopher. He re-interpreted many Vedic ideas and recast them in a psychological and ethical light. He refined the metaphysics of Indian thought by abstracting it from literal interpretations of physical phenomena (such as the Jain idea of Nirvana, where one “flies upwards” to enlightenment, unshackled by the dust of karma). Yet he never saw himself as creative per se. In fact, he had merely discovered something very special, a truth that had not yet been revealed to this world-age in his time. And thanks to him, we of this world-system now know what that truth is. The work of an enlightened being, no matter what aeon or world, is difficult indeed! Can the Buddha have been said to be creative, then? Klostermaier certainly thinks so. In fact, he is creative precisely because he insists that he is not bringing anything new to the table, but unveiling the table itself:

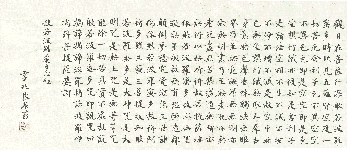

“The great creative geniuses of India, men like Gotama the Buddha or Sankara, take care to explain their thought not as creation but as a retracing of forgotten eternal truth. They compare their activity to the clearing an overgrown ancient path in the jungle, not to the making of a new path” (Klostermaier, 1978, p. 6).

The Buddha declared the Dharma, the eternal law, never appears or disappears, but is only lost and rediscovered. In this sense, can we not say that a new vision of “creativity” is taking place – that is, one of the pathfinder, the discoverer, and the brush-clearer? In this regard I like Coward’s explanation of the Indian idea of language as not something invented, but respoken:

“The creative effort of the rsi – the composer or ‘seer’ of the word – is not to manufacture something new out of his own imagination, but rather to relate ordinary things to their forgotten eternal truth. In this Indian perspective both the technical study of grammar and the philosophical analysis of language are seen as intellectual ‘brush-clearing’ activities which together open the way for a rediscovery of the eternal truth in relation to everyday objects and events” (Coward, 1980, p. 5).

Here we have a different ideal of the artist or poet, not as a creator or maker but as a pathfinder or discoverer. A canvas, a blank piece of paper, a piano waiting for its player to thrill and move an audience – some say that the agent is free precisely because she can create, but she is also free because she is a discoverer of art, music, or philosophy. She is free because she is a discoverer of her own potential.

Is there one correct way of looking at inspiration and imagination? After all, culture is certainly a man-made thing, yet it is also something vital to the life of civilization itself: where there is human thinking there is culture – expressed through art and the sciences – and it cannot be thrown away or destroyed. Is creativity in the sense of innovation and originality by definition something “new?” Or is creativity something timeless, always echoing but never limited by beginnings or endings? I have no idea what the answer is, and it would surely be hubris to believe one can discover it in one lifetime. Nevertheless, one can try. Many have, and there is no reason not to follow in their footsteps: especially if we have an example of such stature as the Buddha.

Speculation and aesthetic originality are all well and good (enjoyment of beauty is painfully important), but the practical achievement of the spiritual goal and experience – as taught by the Blessed One and embodied in the bodhisattva path – is what makes the difference for oneself and others around us.