FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

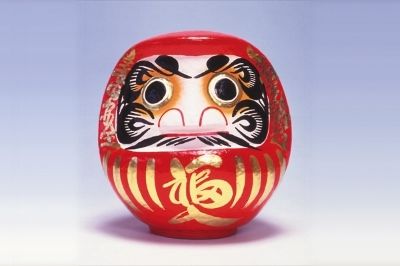

Deconstructing Daruma

The 5th/6th century Buddhist monk Bodhidharma is considered the founder and patriarch of meditational Buddhism, known as dhyana in Sanskrit, Chan in Chinese, and Zen in Japanese. Although he was revered in China, where he is said to have taught meditation to the warrior monks of Shaolin Temple, it is in Japan that Bodhidharma and meditational Buddhism have enjoyed the greatest legacy. Known as Daruma in Japanese, the Indian monk has been depicted in Zen Buddhist painting since the 13th century, when this form of Buddhism first took hold in Japan. While early Chinese and Japanese paintings portrayed him as Indian and rough-looking, with specific physical attributes relating to legends of his life, later Japanese paintings and sculptures of Bodhidharma were often so highly abbreviated, deconstructed, and comical that they appear irreverent to those outside the Zen Buddhist tradition. However, viewed within the context of Zen Buddhist philosophy, such treatment is understandable and even admirable.

Meditational Buddhism is believed to have originated with the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, himself. According to Buddhist texts, the Buddha gave discourses to his followers at Vulture Peak, and one morning, a crowd of 1,200 followers arrived to hear him speak. However, the Buddha sat down in front of them in silence. Time passed, and still there was silence. Finally, the Buddha simply held up a flower. Most of his disciples were baffled, but one of them, Kashyapa, smiled. He had understood the teaching—the flower itself. In Buddhist texts, this is the first reference to the idea of a teaching being transmitted directly from a teacher to the heart-mind of a student without words or texts. Almost 1,000 years later, Bodhidharma, who received the teaching via a line of Buddhist patriarchs reaching back to Kashyapa and was the 28th and last Indian patriarch of meditational Buddhism, traveled to China to pass on his knowledge. As part of his practice, he is believed to have emphasized meditating in the cross-legged lotus position, a posture of balance and stability which allows the mind to become clear and thus enables a direct understanding of reality and consequently, a life lived in an awakened state. Later teachers added such visual aids as paintings and calligraphy or conundrums known as koans to help their students in their practice. Since the concept of direct transmission is one of the most important aspects of Zen, there is little place in this tradition for the texts, images, and rituals that are important elements in other forms of Buddhism.

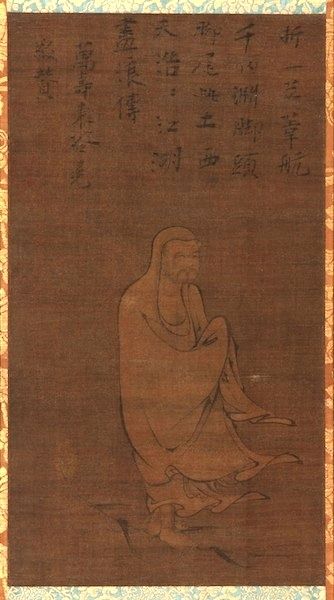

Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi on a Reed. Japan,

Muromachi period, 15th century, ink and color on

silk. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler

Gallery, F1907.141

Meditational Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China in the late 12th century and took hold among the warrior classes, who embraced the key principles of the tradition because it shared many of the values of their warrior ethos, or bushido, including austerity, discipline, and an emphasis on the fleeting nature of life. In addition, the student-teacher relationship echoed the very strong bond between a warrior and his lord. Chinese paintings on silk were used as meditational tools in Zen Buddhist temples and were increasingly copied by local Japanese artists. These included images of Bodhidharma, who is typically depicted as a heavy-set monk wearing red robes, often sporting a beard or stubble and a hairy chest to denote his Indian origins. In some of the best-known examples, he is shown traveling across the Yangzi River floating on a single reed or meditating facing the wall of a cave. Typically, he wears a surly expression and has bulging eyes, a reference to the legend in which he is said to have cut off his eyelids in order to stay awake during meditation. However, these Zen paintings were not devotional objects, iconic images of deities being considered a distraction from the pursuit of a direct understanding of reality and therefore discouraged in the Zen tradition. Instead, these portraits of Bodhidharma served largely as models of resolve and focus for Zen practitioners to emulate.

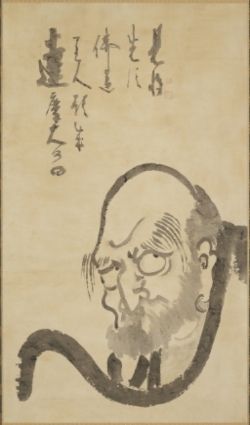

Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), Daruma.

Japan, Edo period, ink on paper. Freer

Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler

Gallery, F1973.10a-c

By the Edo period (1600–1868), both the practice of Zen Buddhism and the style of its art had begun to take on a truly native Japanese flavor as Zen spread among the broader population. One artist in particular, Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768), is credited with reviving and popularizing Zen painting in the Edo period. A Zen priest himself, Hakuin was a talented artist, with impressive brushwork that showed the strong influence of calligraphy. He painted many images of Daruma, often abbreviating the images to a bust portrait with a three-quarter view of the monk’s head and shoulders. He gave Daruma big, round eyes with the pupil at the top of the eyeball and depicted the monk’s body with a single, bold, curving brushstroke. It has been suggested that this type of image is iconoclastic—in the great Zen tradition—since it makes fun of itself: Daruma, the great symbol of spiritual discipline, is depicted comically as a grumpy old fool, turning the image into a sort of Zen paradox. This may well be what Hakuin had in mind—perhaps he intended to emphasize that the image of the Great Patriarch is not as important as his teachings. Hakuin also accompanied certain images with an inscription along the lines of the following: “Look closely at your inner self. Don’t think about wanting to become a Buddha, but realize that you are already a Buddha to begin with.”

Nantembo (1839–1925). One-stroke Daruma.

Japan, 1916, ink on paper. Murray Smith

Collection, Promised Gift to the Los Angeles

County Museum of Art. From kc-shokotan.com

Later Zen artists such as the priest Nantembo (1839–1925) deconstructed the image even further, going so far as to depict the monk meditating facing a wall using a single stroke to create a blob-like form that is barely recognizable as a seated figure. Daruma seems to be disappearing, perhaps turning into the Zen circle, or enso, which represents the reality of the universe. This representation echoes depictions of the monk in sculpture, especially in the folk sculpture of the Edo period and onward, when Daruma dolls were carved out of wood or modeled from papier mâché as a ball with no arms or legs. Such comical representations are believed to have been inspired by the legend that the monk sat in meditation for so long that his arms and legs atrophied and fell off. A ball is the ultimate in sculptural simplicity, just as a single brushstroke represents simplicity in painting.

In Japan, Daruma is so closely associated with the philosophy of Zen that there is an expression “Daruma is Zen.” Daruma is indeed many things in Zen Buddhism. He is the founder of Zen and a symbol of the determination and hard work necessary to become enlightened, yet he may also be depicted with bulging eyes, no eyelids, and no arms or legs—a comical fool or a wobbling toy. Zen Buddhism is a philosophy that tears up sutras, rejects icons, and exclaims, “If the Buddha blocks your way to the truth, kill him,” so the abbreviation, mockery, and deconstruction of its most important spiritual figure are perhaps unsurprising. As Zen has become more and more deeply integrated into Japanese culture over the centuries, it is natural that images of Daruma must be destroyed if one is to be able to see and understand him directly.