Dharma Screenings: Buddhist Film and Pop Culture—Bringing Buddhism to Creative Media

By Raymond Lam

Buddhistdoor Global

| 2015-07-17 | In this three-part series, we explore the Buddhist presence in pop culture media. We first reviewed Toei Animation’s Buddha 2, and in our second entry we interviewed Gaetano Maida of the Buddhist Film Foundation about Buddhist movies. In this third and final article, we analyze how the Buddha has been depicted in entertainment media such as graphic novels and manga, and the ambiguous and conflicted reactions to these trends from the Buddhist world.

A screenshot from Buddha 2. From tezukaosamu.net

A screenshot from Buddha 2. From tezukaosamu.netOur first article in this series was about the film Buddha 2, and briefly analyzed the inspiration behind it, Osamu Tezuka’s influential manga Buddha. Tezuka’s Buddha, begun in 1972 and concluded in 1983, was the first seminal work of fiction to make the Buddha a story-driven protagonist. Unlike the Buddhist biographies and modern retellings that faithfully replicate the canon, Tezuka was unconcerned with generating faith or inspiring spiritual loyalty through his characters. Today, there is still some lingering anger about how brazenly Tezuka depicted the Buddha’s vulnerabilities, emotions, and struggles. Many religious communities share an understandable feeling that religious figures shouldn’t become the subject of secular fiction.

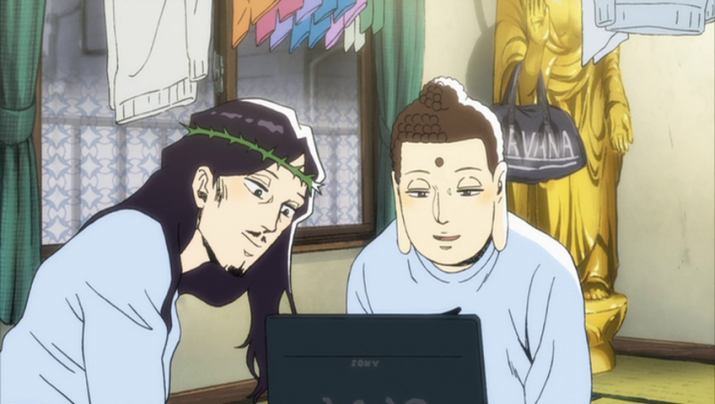

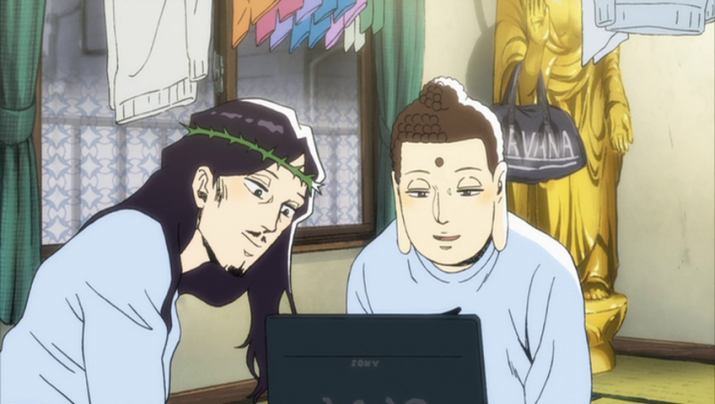

The Buddha and Jesus go online on Saint Young Men. From kronos.mcanime.net

The Buddha and Jesus go online on Saint Young Men. From kronos.mcanime.net Yet there is another franchise that is even more daring, and it is Hikaru Nakamura’s Saint Young Men (Seinto Oniisan). This manga is a satirical take on the escapades of the Buddha and Jesus Christ as housemates renting a cheap apartment in modern Japan. Visual gags, puns, and references to Buddhist and Christian lore and figures abound. Jesus is often mistaken for either Johnny Depp or a Yakuza scion—“It was the will of my father,” he says innocently to a terrified gangster—and in one instance turns water into wine at a public bath. Meanwhile, the Buddha is a placid, thrifty personality who shines with a halo when excited and whose long earlobes are used as train handles by tired commuters.

Neither the religious differences between Siddhartha and Jesus nor the role of religion in contemporary society are this story’s main concerns. Nor are the protagonists trivialized or lampooned in a malicious way. Rather, the fun comes from the quirkiness that ensues when they bumble into contemporary secular life. The manga sold more than 10 million copies in its home country and was subsequently adapted into an anime series and a film. Last year, The Daily Dot published an article noting a growing Western fan base.

When I started following Saint Young Men in 2009, I was sure that I would find at least an online outcry against it. Coincidentally, the comic won the 2009 Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize for Short Work Manga.* Yet the storm of criticism I had expected never came; censure was sporadic. Saint Young Men has even received accolades in Thailand, where its Thai Facebook page has attracted thousands of followers. There was coverage on Coconuts Bangkok of a Thai NGO that accused fans of losing their conscience as well as their respect for the Buddha, but many weren’t impressed with this righteous indignation.

I believe something has changed between the first angry reactions to Tezuka’s work back in the 1980s and the reception to Saint Young Men. Judgment of entertainment-oriented depictions of the Buddha is becoming more varied and divergent. The Buddhist world’s response to the breakneck speed and creativity of pop culture is disjointed, ambiguous, and confused.

I think there are broad reasons why this is so. Firstly, Buddhism is a broad church: we have no formal criteria to inform us how we should treat works that do not portray the Buddha and Buddhist figures in a religious way. Secondly, we simply don’t know what to make of pop culture and whether it’s truly beneficial to sentient beings, which is the goal of any Buddhist enterprise and the criterion of concrete value.

Buddhists have also been slow to react to Dharmic themes in American media. These are no longer mere allusions to rebirth or simple tropes such as Shaolin martial arts, but explicit cultural imports and adaptations that result in “Buddhist” characters with contemporary appeal. Consider Nickelodeon’s wildly popular Avatar: The Last Airbender, in which the first season’s lovable hero, Aang, resembles a Buddhist monk in attire and culture, and in his backstory as an incarnation from an ancient lineage. Avatar is one of the most successful American cartoons in recent memory and is praised for its respectful, non-Orientalist treatment of diverse Asian cultures and character development.

Comic cover from Avatar: The Last Airbender with Aang, Katara, and Sokka in the foreground. From ign.com

Comic cover from Avatar: The Last Airbender with Aang, Katara, and Sokka in the foreground. From ign.com A scene of Aang and Katara's son Tenzin and his family from The Legend of Korra, sequel to Avatar: The Last Airbender. From fanpop.com

A scene of Aang and Katara's son Tenzin and his family from The Legend of Korra, sequel to Avatar: The Last Airbender. From fanpop.comWhile there has yet to be a contemporary American franchise about the Buddha himself, creations such as Aang (and his son in the second season, Tenzin, who is modeled on a Tibetan Rinpoche) betray an implicit acknowledgement of the influence that Buddhist imagery is exerting on creative English-language media. Because this influence is organic and not as visible as the West’s Christian imagery and culture, it is not yet fully understood or articulated, even by the pioneers of these very trends.

Tenzin serves as the teacher and mentor figure to Korra, Aang's reincarnation and the second season's protagonist. From plus.google.com

Tenzin serves as the teacher and mentor figure to Korra, Aang's reincarnation and the second season's protagonist. From plus.google.comWhat is certain is that the debate has shifted from whether the Buddha should be depicted in pop culture to how he should be depicted. Buddhists are unlikely to succeed in persuading others to boycott shows, comics, or films that make use of the Buddha’s figure or Buddhist imagery. Indeed, most Buddhists have no problem with entertainment and creative media per se: many in Taiwan and Thailand generate their own cartoons and graphic novels, though their reach and international appeal are limited compared with their Japanese and American counterparts.

The real question is about who controls the creative process. There is a perceived difference between religions using graphic novels, films, or other media to spread their message and religious imagery and figures used in the secular creative industries to entertain and provoke. Religious groups often emphasize this difference, giving the former a certain moral high ground over the latter—the sense of purpose seems to be “nobler”—right intention, one could say. In this binary divide, Tezuka and Nakamura’s works lean toward the second category.

However, the boundaries are not clear-cut. Even entertainment needs to be consumed within the specific context of the people and the texts that those fictional works are based on (Lyden 2015). Coconuts Bangkok quoted one commenter, Nattaphol Chavananikul, as saying on Saint Young Men’s Thai Facebook page: “Reading his book makes me want to learn more about the Buddha’s biography and I believe that many readers think like me.” It’s common for engaging fiction to motivate audiences to delve deeper. It’s also evident that one need not be a Buddhist to make appealing Buddhist-influenced fiction (in whatever medium). Conversely, there is no reason why Buddhists can’t write, shoot, or draw work so immersive that its world and characters become as beloved as those of Avatar or Saint Young Men.

If Buddhism is to establish a deeper presence in popular culture and Western fiction, it has no choice but to learn from the Tezukas, Nakamuras, and Nickelodeons of the world. Eager audiences are demanding more high-quality stories and character-driven media. By all means have a Buddhist message in a Buddhist-themed graphic novel, film, or show. But be bold, and have fun with it.

* In 2013, Nakamura stated that she saw a resemblance between her Buddha and Tezuka’s. Manga-news.com quotes her as clarifying: “J’ai lu le Bouddha de Tezuka quand j'étais jeune et je pense que ça a été une lecture très impactante. Je n’ai pas cherché à copier son style, mais je pense que pour moi, inconsciemment, le personnage ressemble au Bouddha de Tezuka.” (“I read Tezuka’s Buddha when I was young and I found that it had a great impact. I did not deliberately copy his style, but I think that for me, unconsciously, the character resembles Tezuka’s Buddha.”)

References

Lyden, John C. 2015. “Definitions: What is the subject matter of ‘religion and culture’?.” In The Routledge Companion to Religion and Popular Culture, edited by John C. Lyden and Eric Michael Mazur, 15–16. New York: Routledge.

See more

A screenshot from Buddha 2. From tezukaosamu.net

A screenshot from Buddha 2. From tezukaosamu.net The Buddha and Jesus go online on Saint Young Men. From kronos.mcanime.net

The Buddha and Jesus go online on Saint Young Men. From kronos.mcanime.net Comic cover from Avatar: The Last Airbender with Aang, Katara, and Sokka in the foreground. From ign.com

Comic cover from Avatar: The Last Airbender with Aang, Katara, and Sokka in the foreground. From ign.com A scene of Aang and Katara's son Tenzin and his family from The Legend of Korra, sequel to Avatar: The Last Airbender. From fanpop.com

A scene of Aang and Katara's son Tenzin and his family from The Legend of Korra, sequel to Avatar: The Last Airbender. From fanpop.com Tenzin serves as the teacher and mentor figure to Korra, Aang's reincarnation and the second season's protagonist. From plus.google.com

Tenzin serves as the teacher and mentor figure to Korra, Aang's reincarnation and the second season's protagonist. From plus.google.com