FEATURES|THEMES|Philosophy and Buddhist Studies

Emerging Paradigms and Spiritual Traditions

Since the age of René Descartes (1596–1650) and Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727), our perception of the world has been based on a mechanistic and fragmented vision of reality. We have acted as if we could learn about and control the world from the outside, as if we were separate from it. We have separated the object from the observer. This has led to the creation of a predatory society based purely on short-term economic interests and has produced such a high degree of competitiveness and frenetic consumption that it has brought us to an unprecedented situation never before seen in recorded history: we are all responsible for and, in parallel, victims of the destruction of our own planet. Many species have already disappeared and we can all feel—now more than ever—the fragility of our own existence and that of all humanity.

Since the turn of the 20th century to the present day, avant-garde physics has shown us that reality is based on relational processes. Research into the atomic and subatomic field at the beginning of the 20th century led scientists to face a new and totally strange reality beyond all expectations. They verified that these totalities—whether they are cells, bodies, ecosystems, or even the entire planet itself—are not composed of unlinked parts, but are instead systems organized dynamically and intrinsically balanced, interdependent in every movement, every function, and in every exchange of energy and information. What is real is no longer physical matter, but consciousness, spirit—that which is intangible. This entire process drove forward a change of paradigms comparable, some would say, to the Copernican Revolution.

Today we scientifically understand that reality is holistic, circular, and unifying, and that all of the elements comprising it are interrelated and interdependent. Dualities are complemented without losing their specificity: body and mind, science and mysticism, spirituality and social engagement, theistic and nontheistic religions, East and West, and much more. These convergences call us to a broader consciousness, a new way of doing and being. In the words of Albert Einstein:

A human being is a part of the whole, called by us “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. The striving to free oneself from this delusion is the one issue of true religion. Not to nourish the delusion but to try to overcome it is the way to reach the attainable measure of peace of mind.*

We urgently need to cultivate our spiritual dimension and our human qualities, to be able to integrate and internalize this broader vision of reality. We must feel, and not only know, that we are all part of a bigger whole that is the Earth, that we are all part of a bigger family, which is humanity. In this regard, we simply must return to the origins of spiritual traditions, embrace the legacy of wisdom from humankind’s most ancient practices. We must be capable of transcending this mistaken notion of a self-existing “I” that is independent from the rest, going beyond the narrow and limited vision of egocentrism. Spiritual traditions put the necessary philosophical principles within our reach for the full comprehension of this vision—non-dual, holistic and unifying—as the foundation for today’s emerging paradigms. And this is true, not only with regard to intellectual knowledge, but also to the experiences of men and women who have gone deep into the path of self-knowledge and who can be mentors and sources of inspiration to us along our own journeys.

NASA, ESA/Hubble and the Hubble Heritage Team. From spacetelescope.org

The Avatamsaka Sutra

As regards to Buddhism, one of the central texts in the Buddhist canon that most extensively describes the concept of interdependence that underlies the modern scientific vision, is the Avatamsaka Sutra. The Avatamsaka Sutra is commonly believed to have been compiled in writing some 500 years after the death of Shakyamuni Buddha. According to historiographic data, the sutra was translated into Chinese by the Indian Buddhist monk Buddhabhadra early in the fifth century CE, and became influential through the works of Fashun (557–649) and Zhiyen (602–68), becoming the central text of the Chinese Huayan school and, in the mid-eighth century, of the Japanese Kegon school.

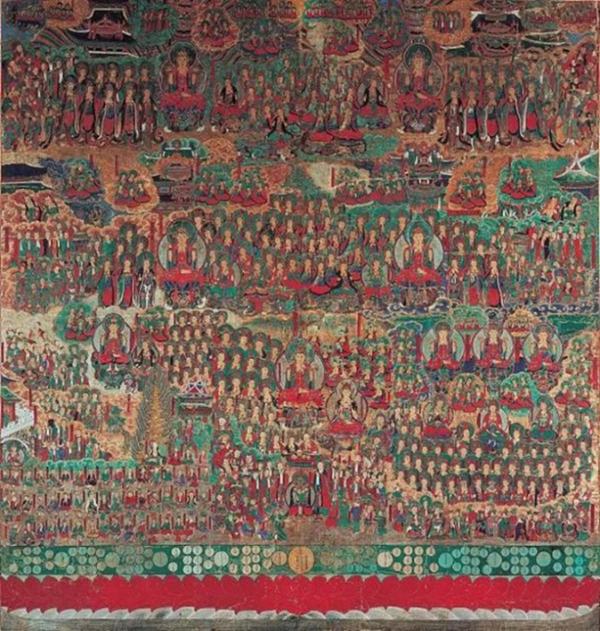

Illustration of the Avatamsaka Sutra at Songgwang Temple in Suncheon, Korea.

From alamy.com

The Avatamsaka Sutra describes in meticulous detail the fundamental notion of Buddhism: the interdependence of all phenomena, or pratityasamutpada in Sanskrit. This concept can be illustrated with the metaphor of the jeweled net of Indra, which describes reality as an indivisible whole in which everything is interrelated and interdependent. Through this image, the Buddha described the universe as an infinitely vast net woven with an immeasurable variety of stunning gems, each of them with an immeasurable number of facets. Every jewel reflects all of the other jewels in the net and, indeed, is one with all of them. An excerpt from the text reads:

Far away, in the heavenly abode of the great god Indra, there is a wonderful net that has been hung by some stunning artificer in such a manner that it stretches out infinitely in all directions. In accordance with the extravagant tastes of deities, the artificer has hung a single glittering jewel in each “eye” of the net, and since the net itself is infinite in dimension, the jewels are infinite in number. There hang the jewels, glittering like stars of the first magnitude, a wonderful sight to behold. If we now arbitrarily select one of these jewels for inspection and look closely at it, we will discover that in its polished surface there are reflected all the other jewels in the net, infinite in number. Not only that, but each of the jewels reflected in this one jewel is also reflecting all the other jewels, so that there is an infinite reflecting process occurring . . .

This metaphor shows us a polycentric and holistic vision of reality: an indivisible and indistinguishable whole of the parts that comprise it, which in turn reflect and contain the totality. Like in the hologram of modern science, each part contains the whole, in each facet of every jewel we find the nature of the Buddha. Vietnamese literature says that the entire cosmos can be found on the tip of a hair, and the Moon and the Sun in a grain of mustard. If we take the example of the human body, we see that the peculiarities of each of the parts—the head, hands, feet, and so on—are determinants for the whole, the body. If something exists or is manifested, it is because infinite causes and conditions have come together and interrelated to make it possible. Nothing can exist on its own, if not through this constant flow of infinite elements in movement and in interaction. Reality is completely dynamic. Our challenge must be to widen our consciousness and transcend the narrow and limited perception of an “I” separated from the rest. Only by doing this, we will be able to build the foundation for a new society.

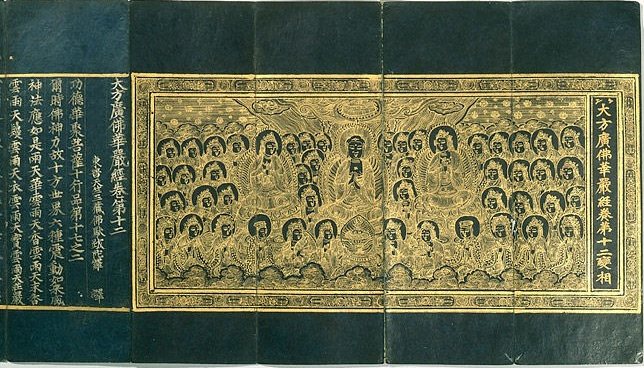

The gold and silver frontispiece of the Avatamsaka Sutra depicting a scene in paradise.

Goryeo dynasty, Korea, mid-14th century. Ho-Am Art Museum. From asianart.com

Montse Castellà Olivé has been a practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism since the late 1970s. With authorization from her master, Lama Thubten Yeshe, she leads meditation retreats and workshops integrating the practice of qi gong. She is an editor and translator of Buddhist texts—of which Women of Wisdom (Snow Lion 2000) by Tsultrim Allione and Dakini’s Warm Breath (Shambhala 2002) by Judith Simmer-Brown merit special mention—and is the author of numerous articles on women and Buddhism and on interreligious dialogue. She is the cofounder and vice-president of the Catalan Coordinator of Buddhist Entities (CCEB), the founding president of Sakyadhita Spain, and chair of the UNESCO Association for Interreligious Dialogue (AUDIR in Catalan). Montse is also a regular contributor to Buddhistdoor Global’s Spanish-language site, Buddhistdoor en Español.

* Einstein, Albert. 1950. The Delusion. Letters of Note.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Buddhistdoor View: Spirituality, Empathy, and Power – Goods to be Reconciled

Spirituality in the Brain

The Missing Self in Buddhism and Psychology

How Does Faith in the Pure Land Teachings Arise?

Standing Together

Buddhistdoor View: Refining the Art of Being Human