FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

Exclusive Interview: The 17th Karmapa and the Buddhist Nuns of the Tibetan tradition

His Holiness the Karmapa in Paris, 2016

His Holiness the Karmapa in Paris, 2016Our initial motive for documenting the lives of Tibetan Buddhist nuns through our photography stemmed from the fact that for many years, the Western world has largely ignored their very existence. Other aspects have since emerged that have enriched this documentary approach as the question of gender equality was being played out before our very eyes with regard to the gradual emancipation of nuns through improved access to education and progressive changes to their status in society.

A number of contemporary Tibetan masters have taken a personal interest in empowering Buddhist nuns and in doing so have become spokespeople, communicating the importance of this cause throughout the world. Among them is His Holiness the Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, head of the Kagyu lineage, who we had the honor of meeting in Bodh Gaya, India in February. His Holiness overwhelmed us with the strength of his presence and won us over with the undeniable sincerity of his attention, patience, and commitment to supporting the cause of Tibetan nuns.

Dominique Butet: Why are you so deeply involved with the feminine cause?

His Holiness the Karmapa: The main thing, in terms of Buddhist teachings, is that men and women are the same. They have the same ability and the same opportunity to uphold the teachings of Buddhism. So looking at it in this way, I want to give the nuns this opportunity.

DB: What are your thoughts on the present situation for Tibetan Buddhist nuns?

HHK: Of course, a lot of progress has been made already. For example, support for the nuns is becoming much stronger, in particular support for their livelihood—that’s really a big deal. In the past, many nunneries in Tibet didn’t receive much support from laypeople and the nuns had to beg for everything. Now the situation is getting much better.

Also, in terms of education, the nuns are now able to study Buddhist texts and philosophy, which is a great advance—especially in India and Nepal, where they are about to receive the first Geshema degrees.*

Tara Abbey, Nepal

Tara Abbey, NepalWhat still needs improvement is, first of all, leadership. The nuns need to develop the ability to direct and lead themselves; to be able to provide their own leadership. Right now, monks provide a lot of leadership, and the [Geshema] classes are being taught by monks. In the future, nuns will be able to stand on their own two feet! Nuns who have completed the Geshema degree will themselves be able to teach other nuns.

The second difficulty for the nuns is the question of full ordination. This question has been discussed for more than 20 years, with a lot of meetings and talks. Now many people are saying that it’s time to actually put it into practice. So my hope and my encouragements are that we can create a situation where [full ordination] can happen quickly within Tibetan society.

Karma Drubdey Nunnery, Bhutan

Karma Drubdey Nunnery, BhutanDB: Could you explain why the lineage of fully ordained nuns died out in the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya?

HHK: I think that there probably were communities of nuns in Tibet. They were established there but then later died out. The reasons why that happened are not clear, so it’s really hard for me to explain much about that. In any case, we would like to start the process of reviving the bhikshuni ordination next year—first within the Kagyu lineage. We had hoped to begin this year but it didn’t work out, so we will try to begin next year.

DB: At the Winter Dharma Gathering for nuns in Bodh Gaya last year, you said that the nuns would first receive the “vows of going forth,” then novice vows, and then “training vows”. Finally, in the fourth year, they would be given the bhikshuni vows. Who could confer these vows?

HHK: Actually there are three different ways we could follow: the first way would be for members of the bhikshu sangha to confer the vows. The second would be to have members from both the bhikshu and bhikshuni sanghas offering the vows. As there is no community of bhikshuni within the Tibetan tradition, we could invite bikhshuni from the Chinese Buddhist tradition, while the sangha of bhikshu would be representatives from the Tibetan tradition. In that way, we could have a dual-sangha ordination. In the third option, we could invite members from the bhikshu and bhikshuni sanghas of the Chinese tradition.

Of these three different methods, the one that has been chosen is the second because it is more in tune with the Vinaya. So we will invite a sangha of Chinese bhikshuni because in the Chinese tradition there is a lineage of bhikshuni vows. I think this would also be a nice way to restore the connection between the two sanghas within the different traditions—by bringing them together to cooperate, I think it will give more power to the full ordination of the nuns and will be very beneficial for all. As most of the nuns who will be taking ordination are Tibetan and Himalayan, I think they’ll have more confidence by taking the vows within the Tibetan tradition. And Tibetan society will also be more accepting of full ordination by having bhikshu of the Tibetan tradition involved.

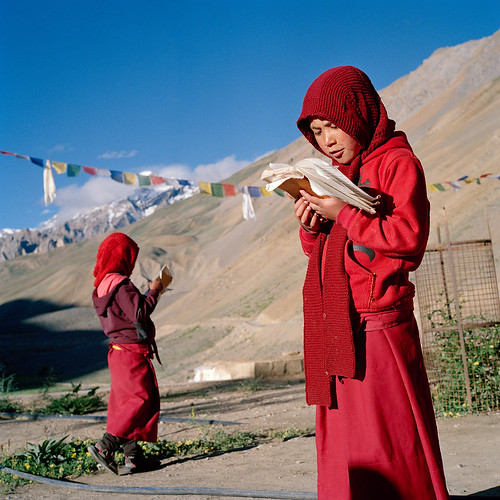

Classroom in Spiti, India

Classroom in Spiti, IndiaDB: In Bodh Gaya this year, you mentioned that you would like to set up a common monastic college, or shedra, for Buddhist nuns. Could you tell us more about that?

HHK: Sixteen years ago, I came to India. And actually in these 16 years I haven’t been able to get a real residence of my own. My own personal situation is difficult; it’s mixed up with politics and other difficulties, and it’s sometimes hard for me to accomplish all my wishes exactly as I would like. So even if I wanted to build a shedra by myself it might be difficult. The main thing is that there are many nuns who are Indian citizens and I think that if they take on the responsibility and build a shedra, then it will be possible. Sure, we have many shedras within different nunneries, but it’s not like bringing all the energies together. As you know, it’s difficult to get enough teachers to teach the nuns. So if we had an institute for the nuns, we could give them a place where they would be able to study at a higher level. But it is not just a question of nuns; there are many other women who want to study the Dharma, so this shedra would be a place for all women to study.

Debating in Spiti, India

Debating in Spiti, IndiaDB: You saw the nuns debating a few weeks ago—what do you think of their ability?

HHK: It has been three or four years since I first saw them debating. The nuns were really beginners at that time—in the first year, there only were one or two who actually knew how to debate. In the second year it was a little bit better, and in the third year I noticed incredible improvements in terms of confidence as well as in the logic they used for debating. So when we saw this progress, we were very, very happy. I’m now sure that the nuns will further raise their level very quickly.

DB: How do you see the future for Buddhist nuns in the Tibetan tradition?

HHK: In Tibetan society we talk a lot about interdependence, we could also say circumstances or auspicious connections. Since we began working with the nuns, all of the connections have turned out very well, and because of this I have developed great confidence and courage. In the future, I’m sure that the teachings of the nuns will flourish.

DB: Your Holiness, thank you for your time and attention.

Tilokpur Nunnery, India

Tilokpur Nunnery, IndiaThe Karmapa’s hopeful conclusion and optimism resonated within our hearts and minds for a long time after we took our leave, and we were reminded of a paragraph from His Holiness’ book The Heart Is Noble: Changing the World from the Inside Out:

“We need to recognize that the most important qualities of today are those that most societies consider as being ‘feminine:’ communication, listening to the needs of others. The coming era will be more ‘feminine’ and women will make a greater contribution.”

His Holiness the Karmapa has been able to accommodate and overcome many obstacles and difficulties related to living in exile; he knows how to meet each day and rejoice in daily life, and is fully committed to wearing the colors of the feminine future.

For the benefit of all sentient beings!

* The Geshe (feminine: Geshema) is a Tibetan Buddhist academic degree for monastics, emphasized primarily by the Gelugpa lineage of Vajrayana Buddhism, but also awarded in the Sakyapa school. It is equivalent to a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy and is awarded after a 17-year course of study. Until recently, the qualification was only open to monks.

Olivier Adam is a freelance photographer and teaches photography in Paris. He is a contributor to various magazines and works regularly for The Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama as a photographer during the Dalai Lama’s visits to Europe.

Dominique Butet is a teacher and a journalist. After meeting Olivier Adam in 2010, she joined his project to document the daily lives of Buddhist nuns across the Himalayas. Dominique contributes to various media outlets, and in 2016 co-wrote a book on meditation for children, Yupsi le petit dragon.

See more

Karamapa: Official Website of His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa

Marpa Foundation (Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche)

Related

Twenty Tibetan Nuns Make History by Passing Geshema Degree (Buddhistdoor Global)

Larung Gar Nuns Push for Gender Equality in Tibetan Buddhism (Buddhistdoor Global)

His Holiness the 17th Karmapa to Empower Female Buddhists with Monastic College (Buddhistdoor Global)

Beauty and the Feminine Buddhist Spirit in Spiti (Buddhistdoor Global)

Losar around Dharamsala (Buddhistdoor Global)

Peace Begins With Us (Buddhistdoor Global)

The Druk Amitabha Kung Fu Nuns: Combining Martial Arts and Meditation (Buddhistdoor Global)

Attending the Kalachakra (Buddhistdoor Global)