FEATURES|COLUMNS|Creativity and Contemplation

From Chamonix to Chenrezig and Thangkas to Mountain Landscapes – The Story of Neljorma Tendron

Marie-Laure Jacquet (Neljorma Tendron) grew up in a very outdoors-oriented family in France. Always in the snow, she learned to ski at a very early age. As she progressed, her father wanted her to become a ski instructor. In retrospect, she appreciates having been so strongly encouraged in that direction as it became her own path. She attended the École du Ski Français in Chamonix and excelled at alpine skiing, becoming a professional guide and patroller. Decades later, having moved to Colorado, Tendron is reconnecting with her early years in the mountains of France, loving the mountains and vistas of the greater Boulder area. She deeply appreciates the beauty of nature, which allows her to feel resourced in solitude.

From India to Karma Ling: retreat in France

By age 24, still in France, Marie-Laure felt she didn’t know what direction to take with her life. Her boyfriend had committed suicide, and, deciding to leave everything behind, she bought a ticket to India. Arriving there in a Buddhist community, something in her awakened: the Buddhadharma made sense to her, she felt understood. The Dharma became the main focus of her life and after six months in India she returned to France, where she moved to Shangpa Karma Ling Meditation Center in Arvillard, a mere 40 kilometers from her hometown. She stayed there for 11 years, including three years in retreat, and there she became Neljorma Tendron. At Karma Ling she was very fortunate to have the Dharma taught in French by Lama Denys. The head Kagyu lama, Kalu Rinpoche, would also come to the center every so often to teach. The teachings were given in French, but the practices were in Tibetan only, so students were obliged to learn Tibetan, which was a great blessing. The sounds and syllables carry a blessing on their own and instill in students an original taste of the Dharma. The liturgies have now also been translated into French, in metered form.

Karma Ling was, and still is, a lay nonmonastic community. Kalu Rinpoche would come every two to three years during the 1980s, and during her time there Tendron had three interviews with him. Outwardly, her retreat was very disciplined, with plenty of structure—a typical Shangpa Kagyu retreat. Retreatants could not lie down for the duration and there were no heaters, so it was quite cold. They practiced and slept upright in the traditional Kagyu meditation box. Students would apply the exact instructions they had received and follow the program. Tendron says it was actually easier because there was so much structure. She was very motivated to engage because she had had to wait several years before beginning the retreat. Previously, when she was ready to enter retreat, it turned out she was pregnant with her son, so she had to wait while his father did retreat first. After that, they traded places, and she went on retreat while her son was looked after by his father. Tendron describes herself as the kind of person really made for practice in a retreat setting. She even considered becoming a nun very early on because she likes to do things completely, but at Karma Ling everyone was a lay practitioner. She never seriously considered doing a life-long retreat, as some do in France, even knowing it might be the best path to follow. Doing three months of retreat every year also appeals to her as an ideal scenario. Kalu Rinpoche suggested doing this every year in winter.

From France to the US: retreat in California

Kalu Rinpoche attained parinirvana in 1989 and Tendron met Lama Tharchin Rinpoche in Europe in 1997, which lead to her decision to emigrate to the US. In 1998, she arrived at Pema Osel Ling, which housed a sizeable community of Tibetan and Western practitioners. Although there were many Tibetans, no one was teaching Tibetan language. Tendron felt inspired to help practitioners better understand the original language of the Dharma in the texts and liturgies. In her second three-year retreat, led by Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, she constructed a comprehensive curriculum to help others learn. Since 2012 she has added several more levels and is adding a course on studying a Buddhist text in Tibetan prose for 2018. She teaches literary (not colloquial) Tibetan, including reading, grammar, and word-by-word understanding of sadhana. She teaches online, to people all over the world, in small, personalized classes.

Tendron says her second retreat, this time a Nyingmapa retreat, was more relaxed, more inwardly complete, meaning she went further into upheaval wherein past karmic knots could surface and be released. She felt the purpose of being there was clearer for her. With deeper motivation and strong will, she could recognize rigpa, and then just apply her own inner discipline. She had more maturity and confidence than the first time around. She points out that many people have various outer obstacles during retreat. But for her it has been the opposite: retreat feels like her natural habitat, whereas the outer world is more challenging!

Nature and retreat: perfect companions

Having grown up being alone in the beauty of nature made it easy for Tendron to enter into a three-year retreat. She had no anxiety about being alone because her whole youth was steeped in appreciating nature, often as a lone skier or alpinist. When she became a Buddhist her ease in nature was a big support for her practice. Resourcing herself in nature is her reset button. Her mind, her joy are reset and any disconnects are healed. Tendron’s son, her son’s father, her daughter-in-law, and her husband have also all completed three-year retreats. Her 20-month old grandson says “hi” and “bye”to an image of Guru Rinpoche by name—already knowing who he is. Their lama, Tulku Sang Ngak Rinpoche, says it is generations of Buddhists like them—who are not Asian, and are devoted to the lineage and to practice—who will support the longevity of the Dharma in the West.

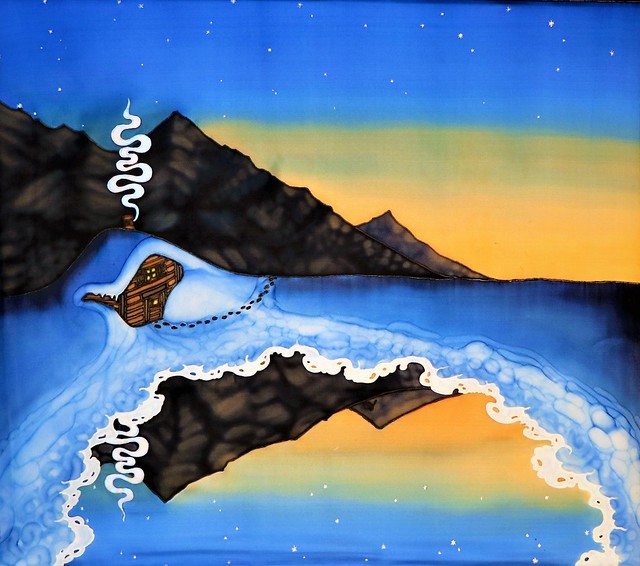

Silk painting: mountain landscapes

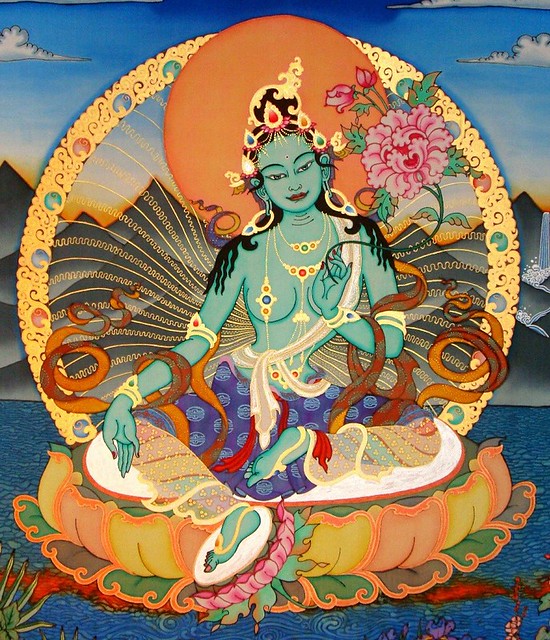

In her youth, Tendron had wanted to attend art school, but her parents did not support the idea at all. Her sister, however, was making art using the Serti silk painting technique—so by adapting what she observed and then teaching herself. Tendron was able to pick it up, drawing inspiration from scenes of the French Alps. Later, deity images were also a way to adapt her techniques and to learn about color. This method of silk painting is different from batik: both sides of the fabric are visible, as with batik, but the difference is that by isolating each color, silk painting can employ thinner lines to draw finer details by wrapping the color using rubber of different colors instead of wax. Applied on white silk, this rubber-like medium passes through the fabric, sealing one area, then by applying the color inside these areas, there are many shading possibilities. Lama Tharchin Rinpoche, himself an accomplished artist, enjoyed Tendron’s work very much, an,d she has given him many thangkas.

Master silk painted thangkas

The thangkas are all about 5x4 feet (1.5 x 1.2 meters) with brocade borders. When Tendron has an idea for a deity painting, it becomes an obsession. She claims that Dzambhala insisted she should paint him! It is the first painting she completed since her move to Colorado. Dzambhala is not one of the most well-known Nyingmapa deities and she hopes others will come to know and enjoy him. Many of her works are by commission, but this Dzambhala has been painted for someone who has yet to be identified. “Dzambhala means ‘Precious Golden Deity,’ who gathers or brings the wealth of spirituality or the Dharma and material security or accomplishment to our lives.”*

Meditation and creativity intertwined

“It happens in the evening, in the dark, when I close my eyes. If I think about the lama, pray to the lama, even informally, just by staying present I can develop an inspiration for seeing something. Being a visual artist, you want to see something, and incredible images do come. Creativity can be explored with meditation.”** She describes how surrrealist Salvador Dali was doing this, not through devotion, but by putting some type of chemical into his eyes to stimulate the production of an image. Practitioners know it is not merely the eye that sees, it’s deeper inside; the mind and heart are connected through the eyes. Perceptions may come too quickly, or too colorfully, too many at once, transforming all the time, but sometimes one can catch an image and calmly bring it forth. This is also related to dream yoga, and happens with many different kinds of creative expression. Tendron’s beautiful landscapes with a cabin and lake came from one of her nighttime meditation sessions. She sometimes has difficulty sleeping, so she keeps paper and pen beside her bed to quickly draw images whenever they arise. Just as in dream practice, one can write or draw everything down as it arises at night because otherwise memory changes it, or one simply forgets. Pure creative expression in myriad forms is, on the relative level, what our Buddha-nature is to the ultimate level.

May we all experience the simple joys of life, as in our youth, and be never separate from our true nature, which is our birthright as sentient beings on the path to awakening.

* From The Teachings for the Dzambhala Empowerment (His Holiness Gyalten Sogdzin Rinpoche)

** Personal Conversation with the Artist, 11/4/17.

A Vajrayana Buddhist practitioner since 2000, Sarah C. Beasley (Sera Kunzang Lhamo) spent more than six years in retreat under the guidance of Lama Tharchin Rinpoche and Thinley Norbu Rinpoche. She is an experienced teacher, writer, sculptor, photographer, dancer, and Iyengar yoga practitioner. Sarah offers a workshop, “Meditations for Death, Dying & Living,” based on the text Vajrasattva Ceremony for the Dead (Concise Nay Dren). For more information, visit Moondrop.

See more

Online Tibetan Classes (Online Tibetan)

Silk painting mountain landscape (Tendron Joys Facebook)