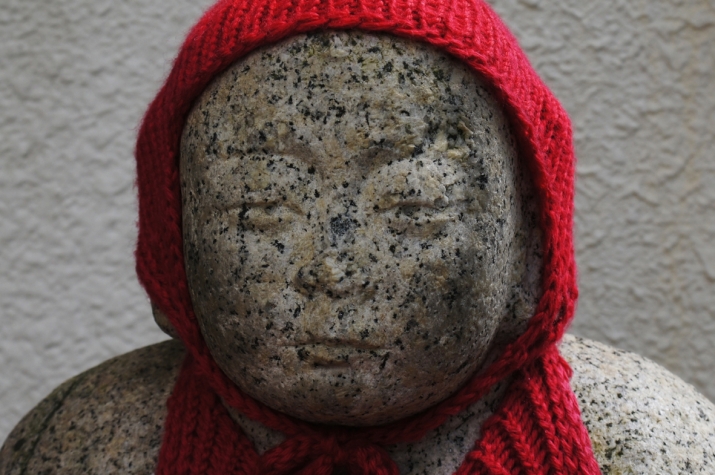

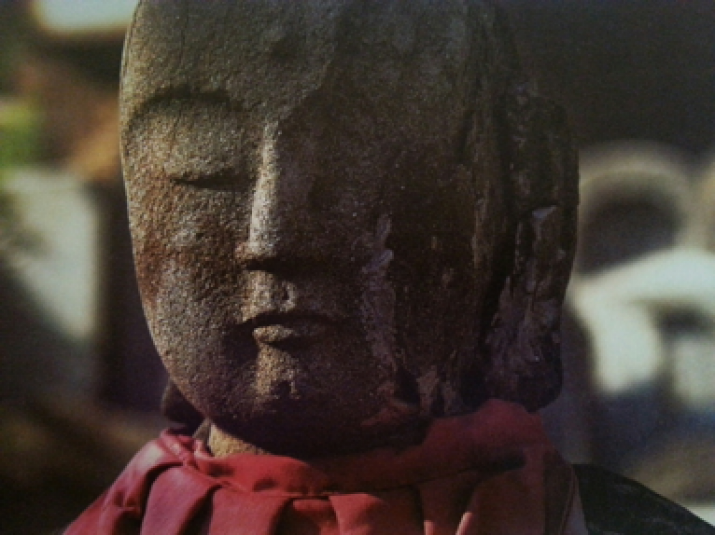

Shimizu, who was born in Hiroshima five years after the bomb was dropped, has many memories of the scars of the atomic bombing on his native city. His childhood recollections include the burned stairs of a department store, the shadow burnt onto the wall of a bank, and the story of young Sadako Sasaki, who had become ill with leukemia because of the bomb and folded 1,000 origami cranes in the belief that this would grant her wish to be healed. In 1975, when he returned to the city after attending college in Tokyo, Shimizu began photographing traces of the bombing. It wasn’t until 2009, however, when he was guiding a friend around the A-bomb Dome in the Peace Memorial Park, that he came across some very haunting evidence of the explosion—a small Jizo figure wearing a red bib in the nearby temple, Sairen-ji. The surface of the figure was rough and had black burn marks from the intense heat of the bomb blast; only the area below the robes remained smooth as it was sheltered from the explosion. Shimizu remembers thinking, “This Jizo recalls perfectly what happened on August 6, 1945, and he is trying to tell us about it” (Shimizu 2013, back cover flap).

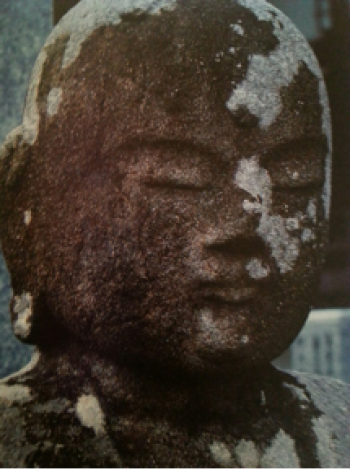

The scarred statue at Sairen-ji compelled Shimizu to search for more of these stone hibakusha, or “survivors of the bomb.” He spent four years tracking them down, and found them at a number of temples throughout the city. Becoming increasingly fascinated by these stone representations of the compassionate Buddhist deity that had borne silent witness to the devastation of his home city—which are therefore known as “Hibaku Jizo”—he decided to capture the “memories” of the statues by photographing them. At first glance, some of the figures in the photographs appear to have been ravaged by time or by Japan’s capricious climate. However, on close inspection, it is apparent that the damage was not natural but instead caused by the heat or force of the atomic blast. Some figures have rough or darkened surfaces due to the heat, while others are cracked or have crumbled faces. Some have lost their heads entirely (later lovingly replaced by people from the neighborhood). One has a crack on his face that resembles a keloid, or raised scar. To Shimizu, the Jizo figures seemed to have received some of the same wounds—the burns, the keloids, and the missing body parts—as the people of Hiroshima. Through his photographic portraits of these Jizo figures, Shimizu portrays the pain, grief, and terror of Hiroshima’s inhabitants, whose trauma was unlike anything humans had previously experienced.