FEATURES|THEMES|Interfaith

Interview with Ana María Schlüter Rodés, Founder of Zendo Betania

Ana María Schlüter Rodés was originally interviewed for Buddhistdoor en Español. The following is a translation of that interview.

In Spanish-speaking countries, Buddhism is located amid a historically Catholic setting. Relations between both religious cultures—Buddhist and Catholic—cover a broad spectrum: from mutual exclusivism to fruitful dialogue, moving through diverse degrees of reciprocal indifference. With regard to the two spiritual traditions, Ana María Schlüter Rodés embodies what she appropriately terms “religious bilingualism.”

In this interview, Ana María talks to us about her spiritual path and practicing Zen in a Christian environment.

Ana María Schlüter Rodés. Image courtesy of Zendo Betania

Ana María Schlüter Rodés was born in Barcelona in 1935 to a German father and a Spanish mother. Because of the wars, she lived in Germany from the age of 2–14, and in Spain again after 1949. She studied philosophy and literature in Barcelona, Hamburg, and Freiburgim Breisgau (Germany), and Nijmegen and Utrecht (Netherlands), later doing her doctorate in Barcelona, with a dissertation on the topic “Why Do Some See and Others Look but Do Not See?” Since 1958, she has been a member of the religious organisation Women of Bethany, living in the Netherlands, the country where it was founded, from 1958–65.

Ana María was a lecturer on ecumenism at several Spanish universities until 1987, having been invited by a lecturer at the Higher Pastoral Institute in Madrid at an ecumenical meeting organized by a Swedish journalist in Sigtuna in 1968. At that time, she lived in an outlying neighbourhood of Madrid, maintaining a deep social commitment, including acting as the secretary of her neighborhood association.

Ana María became the assistant and translator of Jesuit and Zen master Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle (1898–1990) in 1976. In 1985, after lengthy stays in Japan, Yamada Kōun Roshi authorized her as a Zen teacher, and some years later Kubota Jiun Roshi appointed her as a Zen master. With her disciples, she created the Zendo Betania Centre in Brihuega (Guadalajara, Spain), where she has lived since 1988. Today, she accompanies numerous people on the path to Zen in Spain and Mexico. She also speaks at conferences and publishes articles and books.

Buddhistdoor en Español: You are a consecrated Christian who practices and teaches Zen. Tell us about the spiritual path that led a Christian to becoming recognised as a Zen master.

Ana María Schlüter Rodés: I have indelible memories of childhood, like a little yellow flower in the grass coated in morning dew, in the garden of my grandparents. And the smell of the earth when collecting beechnuts among the fallen autumn leaves in a dense beech grove glistening with drops of water, to exchange them for vegetable oil. The mystery of kindness and simplicity, what one perceives in a flower, a forest. . . . Also, later, the memory of a mountain totally shrouded in clouds and walking on high there from the fog to a space full of mystery, Montserrat. An abridged Bible, among the few books that were on a window sill, strengthened my awareness that human beings are never abandoned and are always shored up, in the midst of everything, and accompanied by Someone who wishes them well.

My studies and rational development led to a time of a crisis of this “dark faith,” based on experiences that reason simply could not explain. Until I understood, thanks to Blaise Pascal (Pensées), that the noblest function of reason is recognising its limits. Then a very vivid and, at the same time, a very simple realization, formlessness, of Christ-Love, could happen.

This time, which was crucial in my life, progressively aroused two questions in me:

1. How can I cultivate this experience so that it may mature?

2. How can I help others awaken to this reality?

This led me to the community of the Women of Bethany, a consecrated life in the midst of the world. Along a different line, I wrote my doctoral dissertation on the topic “Why Do Some See and Others Look but Do Not See?” But I did not fully find what I sought until I found Zen.

My first contact was with Jesuit Enomiya-Lassalle, a pioneer in interreligious dialogue.* He opened the way for Christians to practice Zen and was a Christian Zen master recognized by Japanese Buddhist Zen master Yamada Kōun Roshi. He created a Zen center called Shinmeikutsu (Cave of Divine Darkness).** He came to Spain in 1976, invited by Ignacio Oñatibia, theology professor in Vitoria (Basque Country) and the Reparadoras de Los Molinos religious order in Madrid.

Enomiya-Lassalle had worked with the Second Vatican Council in writing a text, contained in the council document Ad Gentes, article 18, which reads: “Carefully consider the way in which to take on the ascetic and contemplative traditions in Christian religious life, whose seed God frequently scattered among the ancient cultures before the proclamation of the Gospel.” The first draft spoke explicitly of Zen and yoga, although later he left it open to more traditions.

Enomiya-Lassalle introduced me to Yamada Kōun Roshi and, after intensive stays at the San’un Zendo in Kamakura, Japan, he approved me as a Zen master in 1985.

BDE: How did Zendo Betania come about and what is its function?

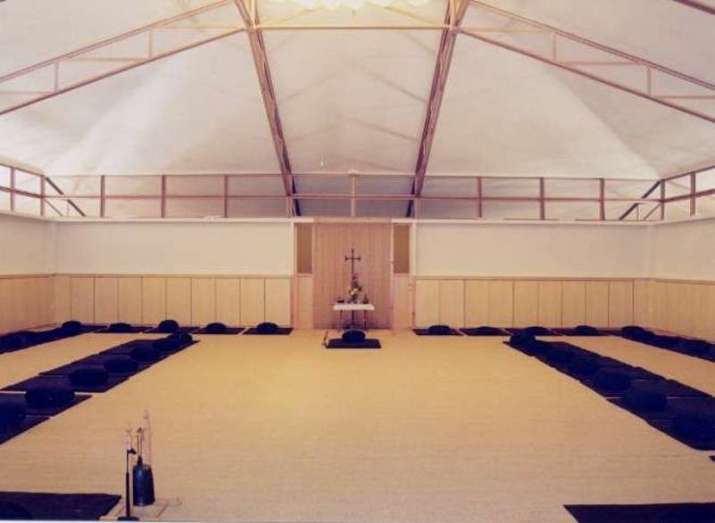

AMSR: Together with my disciples, we created Zendo Betania in Brihuega (Guadalajara). We searched for the perfect location, guided by a text on the Zazen Yojinki by Keizan Zenji: “In an isolated valley . . . near clear water. . . in the proximity of a river . . . under trees . . . far from centers of power and wealth, far from those who want to fight and dominate.” Further, in our case, it had to be financially affordable and not be further than 90 kilometers from a central, large city, so that we could travel there with relative ease, given that it was not a monastery but a Zen center where laypeople could come, who worked and lived throughout Spain and beyond.

Through zazen, Zendo Betania aims to help modern mankind re-encounter their own deep roots in a climate of ecumenism and respect toward all people and beliefs, and in harmony with the Christian faith. It leads to cultural and solidarity projects with disadvantaged peoples and populations, both inside and outside Spain.

The meeting between Buddhism and Christianity is a historic event that is of great importance in our times. It is significant for the peace and good of humanity and the Earth.

As in all real human encounters, Buddhist-Christian interreligious dialogue transforms both parties, without either losing their identity. They re-find it at a deeper level and it even ennobles them. For this reason, the Buddhist must really be Buddhist and recognize him or herself as such, and the Christian truly Christian, also recognizing him or herself as such.

Image courtesy of Zendo Betania

Only from this viewpoint can intra-religious dialogue be understood; a dialogue between two spiritual traditions in a single person, like the fact that at Zendo Betania, Christians practice Zen without this creating either a Christian Zen or a Zen Christianity.

This meeting between Zen and the Christian faith produces a twofold conversion: on the one hand, it makes it possible to enter the Zen perspective and, on the other, it leads to discovering a deeper dimension of the Christian faith itself. Deep down, the conviction beats that the Holy Spirit is present in all human beings with good will. Christians, moved by Him, feel great happiness every time they recognize His appearance among humanity and this awakens in them a desire to learn from everyone and to know and love God, Father of all of us, deeper and deeper.

The Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council, held in 1965, exhorted “that through dialogue and collaboration with the followers of other religions, carried out with prudence and love and in witness to the Christian faith and life, they recognize, preserve, and promote the good things, spiritual and moral, as well as the socio-cultural values found among these men.” (Nostra Aetate 2).

Zendo Betania in Brihuega. Image courtesy of Zendo Betania

Zendo Betania in Brihuega. Image courtesy of Zendo BetaniaBDE: Could you tell us a little about Zendo Betania’s presence in Latin America.

AMSR: In September of 1990, responding to repeated invitations, I went to Mexico City for the first time to introduce Zen, and I continued visiting until 2014. After 25 years, during which Zendo Betania was also established in other cities, I appointed an authorized person to replace me at these introductory sessions and sesshin. Two more people give these introductions, in Mexico City and Nezahualcóyotl, respectively. At present, these contacts with me continue via Skype with disciples and local groups, mainly in Mexico City, Nezahualcóyotl (State of Mexico), Monterrey (State of Nuevo León) and Torreón (State of Coahuila), as well as initially in Tampico. Several disciples have come to Brihuega in Spain to receive further training.

In 2002, Pedro Flores, a Zendo Betania Zen master, went to Argentina and continued visiting each year until 2018. Zen carries on there now, with groups in Buenos Aires and in Argentine Patagonia, with two people in charge of introductions. There are also people from Argentina who come to Zendo Betania in Spain. There is a disciple of Zendo Betania in Bogota, Colombia, and people from several Latin American countries who have contacted me personally.

In 2016, a Zendo Betania teacher, who went to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Ecuador, split from Zendo Betania after 30 years and now belongs to the Sanbo-Zen line.

The quarterly newsletter Pasos, by the Zendo Betania Zen School—with an internal circulation—has the main objectives of prolonging the orientation on the path given in the sesshin, and helping to assume the path of Zen in the Western cultural and Christian tradition.

Sesshin reception in Cuernavaca. Image courtesy of Zendo Betania

Sesshin reception in Cuernavaca. Image courtesy of Zendo BetaniaBDE: How would you define Zen?

AMSR: At present, I am wholly devoted to the task of “plowing the ground of the soul,” so that it is sensitive and permeable to the deepest dimensions of reality.

I intensively believe in the light of the soul of all human beings. Two great men expressed this clearly, at very distant times in history, distant also geographically and in the religious-cultural framework: Siddhartha Gautama the Buddha and Saint John of the Cross, a 16th century Christian mystic. The first exclaimed at the time of his awakening, of becoming the Buddha: “All beings are enlightened beings, but due to their faulty way of thinking and attachment to themselves they do not realize it.” Saint John of the Cross wrote: “This light is never lacking to the soul, but because of the forms and the veils” (Ascent of Mount Carmel II,15,4).

What path does Zen propose to attain the awakening of the soul’s light or—stated more properly in the language of Zen—the root or essential nature of oneself and of all things? According to words attributed to Bodhidharma that summarize what is essential, Zen is:

A special transmission outside of all doctrine,

Is not based on words or letters.

Points directly to the human heart and

Makes one see reality (kensho) and to live awakened (jobutsu).

This dialogue took place in eighth century China: The great master Yakusan Igen was seated (in zazen) and a monk approached him and asked: “What do you do while you are sitting so completely still?” The master answered: “I sit in the unthinkable (fu shiryo tei).” The monk insisted: “How does one sit in the unthinkable?” The master replied: “Not thinking” (hi shiryo). This is the essential art of zazen: sitting, not thinking, in the unthinkable, beyond discursive thought. Centuries later in Japan, Dōgen Zenji added: “And this unthinkable sustains me.”

I’d like to add that Zen is a “road to go back home,” with words from the Zazen Yojinki by Keizan Zenji. It is not a method or a technique, but an art. A pianist has to know the piano keys well, but this in itself will not make her a pianist; she will not start to really be one until she no longer has to think of the keys—when only the music exists. Strictly speaking, Zen is not meditation, during which one works on the senses and faculties of the soul, but more like what Sts. John and Teresa refer to as contemplation.

The result of reflections over the course of the years, based on practice, has been captured in books published by the Editorial Zendo Betania, including: El verdadero vacío, la maravilla de las cosas (True Emptiness, the Wonder of Things; 2008), on true awakening, based on writings from the early centuries of Zen, Atrévete con el dragón vivo (Do not Fear the True Dragon; 2009), on how to properly practice zazen from the “ancients,” Guía del caminante (Walker’s Guide, 2003 and 2011), on the ethical course, and Palabra desde el Silencio I & II (Word from Silence; 2005/11 and 2013).

BDE: How does practicing Zen help one to live a more profound Christian experience?

AMSR: As I progressively delved deeper into the path of Zen, I kept discovering that not only was I learning a new way of sinking down into the mystery—which goes beyond the limits of objective thought—but I was also learning something more, something that at first I could not have even imagined: a new “language” that led me to discover and express myself in a new way, which opened up new horizons offering new possibilities of becoming aware of certain dimensions of experience. So, although the ultimate and ineffable reality is one and the same always, the religious framework in which it is experienced influences the possibility and way of experiencing it, as well as the interpretation of the experience.

All cultural and religious frameworks are the expression of an experience and, in turn, foster a specific way of perceiving reality and interpreting experience. A new framework, such as Zen Buddhism for Christians, provides new language possibilities for expressing what is experienced and also creates new perception possibilities, as well as a new instrument to rescue from oblivion that which had been realized.

Michael Amaladoss SJ attributes a prophetic meaning to Christians who come to Zen or other paths. It is not about creating a third and superior religious identity, but instead about living a fruitful tension between Zen and the Christian faith that favors the flow of dialogue that today is more necessary than ever to act as an important counterbalance to fundamentalism.

“Assume,” as read in Ad Gentes article 18, does not mean adapting one-off items, methods, or techniques. That would be colonialism at a spiritual level, as Ama Samy SJ says, who is a Zen master in India. The council goes further and invites us to a living encounter, not merely intellectual, between Zen and the Christian faith.

The experience is that what is emphasized by one does not exclude what is emphasized by the other, but instead assumes it in some way, either as a root and origin to be authentic or as a manifestation of the experience itself to be true. Thus, the love that is not rooted in mystery is not truly Christian love and falls easily into activism. Just reading The Hymn to Love by the apostle Paul suffices, which is in the first letter to the Corinthians:

If I give all I possess to the poor and surrender my body to the flames, but have not love, I gain nothing. (1 Cor 13:3)

And, on the other side, for Zen there is no true awakening or enlightenment if it does not lead to compassion.

* Baatz, Ursula. 1998. Hugo M. Enomiya-Lassalle. Ein Leben zwischen den Welten. Zürich/Düsseldorf: Benziger Verlag.

** Schlüter, Ana María. 1979. “La cueva de la oscuridad divina” in Vida Nueva, issue 1,202, pp23–30.

References

Arokiasamy, Arul M. 1994. Why Did Bodhidharma Come to the West? India: Bodhi Zendo.

Lee, Chwen Jiuan A. and Thomas G. Hand. 1990. A Taste of Water. Christianity Through Taoist-Buddhist Eyes. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Enomiya-Lassalle, Hugo M. 1990. The Practice of Zen Meditation. London: Thorsons.

Enomiya-Lassalle, Hugo M. 1974. Zen Meditation for Christians. La Salle, Ill: Open Court.

Habito, Ruben L. F. 2006. Total Liberation: Zen Spirituality and the Social Dimension. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Schlüter, Ana Maria. 2001. “Inner Peace and Social Action” in FAS (ed), Inner Peace in Social Action. The Tiltenberg, Vogelenzang, pp15–23.

Schlüter, Ana Maria. 2000. “Deux expériences humaines fondamentales”, in Gira et Scheuer (ed.), Vivre de plusieurs religions. Les Éditions de l’Atelier, Paris, pp181–84.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

From Buddhist and Christian Practices to Societal Harmony: A Conversation in Hong Kong

Buddhistdoor View: Dialogues between Mahayana Buddhism and Orthodox Christianity

Theravada Buddhism and Teresian Mysticism: A Reflection on Interreligious Dialogue

The Wild Geese of Buddha and Christ

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Carmelite and Chan/Zen Interfaith Conference to Be Held in Avila, Spain in July 2020

Christians and Buddhists Mark the 50th Anniversary of the Passing of Thomas Merton

Vesak Celebration: Vatican’s Message Asks Buddhists and Christians to Promote Peace, Nonviolence