FEATURES|THEMES|Travel and Pilgrimage

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part Two: From the Great Temples to Early Modern Tibetology

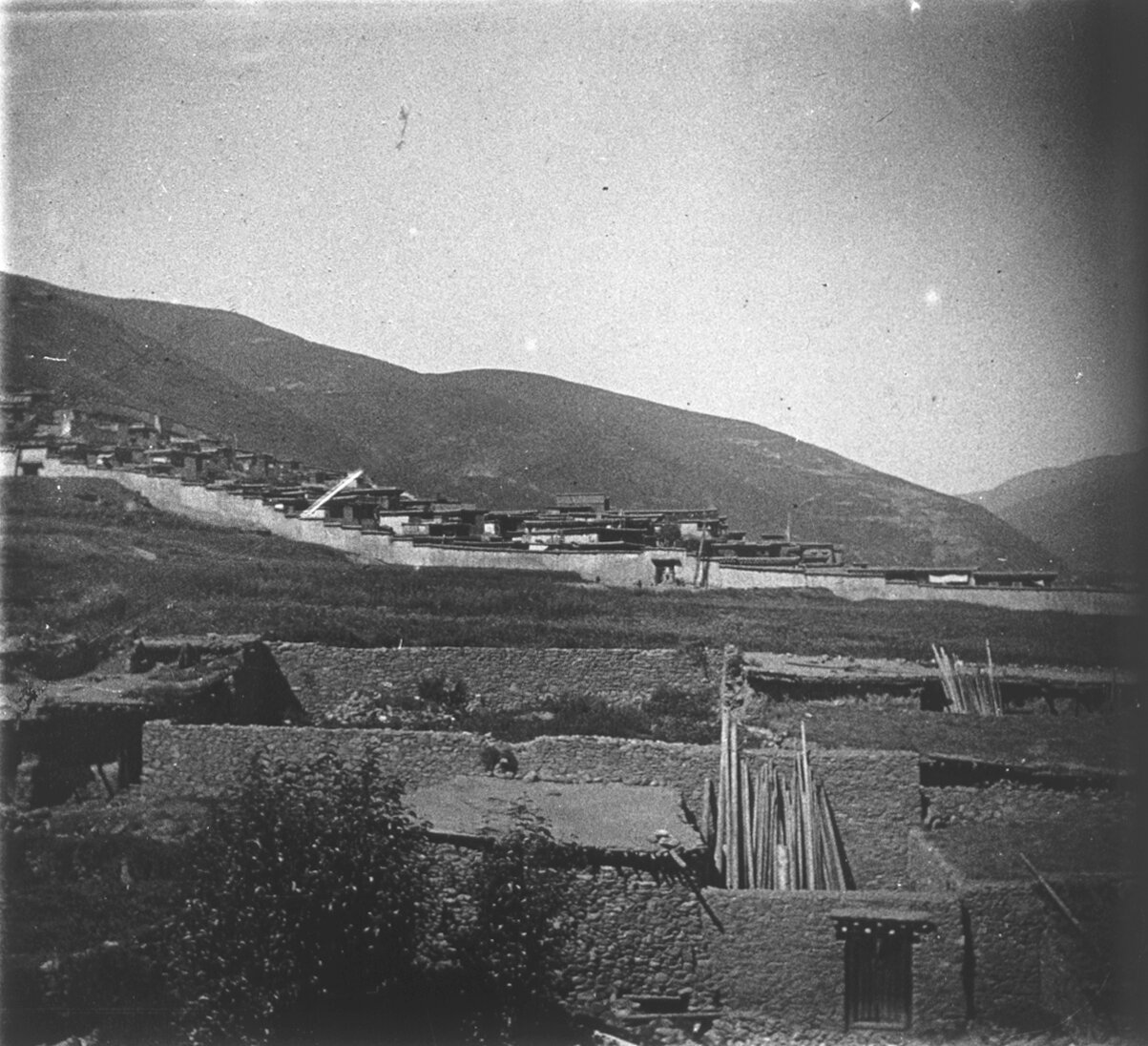

Tchangou Monastery in Kham, northwestern Sichuan, September 1909. Jacques Bacot photographic collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

In his second journey to Tibet from 1909–10, Jacques Bacot visited several important religious sites—mostly monasteries—in Kham (ཁམས་།), such as Tchangou/Drango (Brag mgo) and Lithang/Litang (Li thang), which were towns surrounding a gompa, and the monasteries of Chontain/Chateng (Phyag phreng), Conkaling/Kangkar Ling (Gangs dkar gling) and Sam pil ling/Sampel Ling (Cha ’phreng bSam phel gling). As a traveler, Bacot converted his formerly anthropological agenda to, more broadly, a cultural quest: a search for genuine Tibetan artwork and literature. He found himself admiring the architecture of the temples, the fine works of art they contained, and fabled collections of Tibetan texts. This enjoyment was not simply an “armchair” kind of admiration: Bacot would go on to assiduously communicate the sights, sounds, and people he encountered in Tibet as legitimate subjects of serious study to a Parisian academic audience.

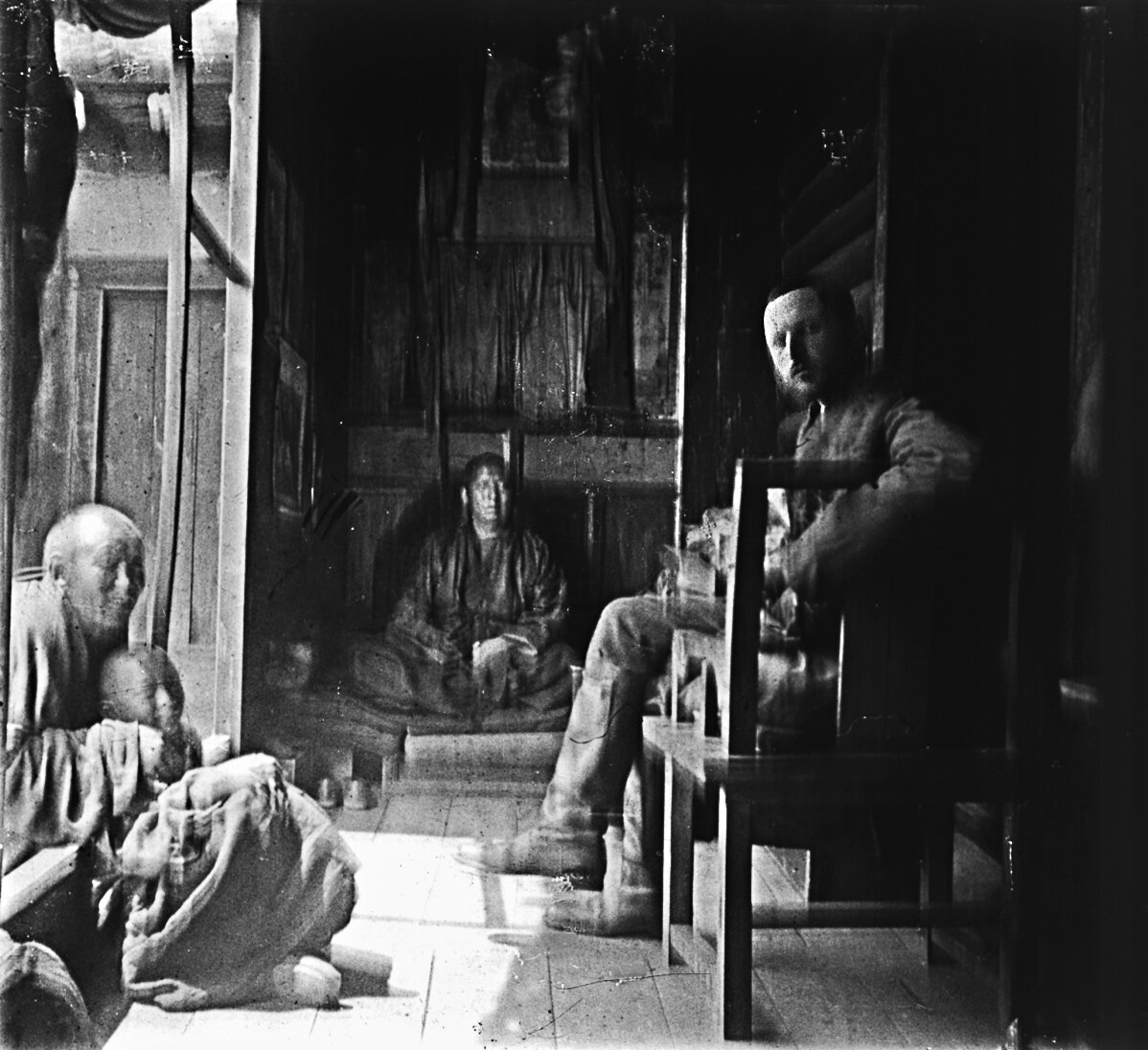

Jacques Bacot with a figure reputed to be Lobzang Pelden Tendzin Nyendrak Pelzang, or the

third Brag dkar sprul sku/Vajradhara Drakkar (Brag dkar rdo rje ’chang), in Kham. Photo

presumably by Adrup Gönpo, September 1909. Jacques Bacot photographic collection.

© École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

Throughout this particular trip, Bacot met with important figures of Buddhism in Kham, many of them steeped in local folklore and beliefs. One of these was Lobzang Pelden Tendzin Nyendrak Pelzang (1866–1929), whom Bacot met in September 1909 in Tchangou. He was the third Brag dkar sprul sku, or Vajradhara Drakkar (Brag dkar rdo rje ’chang). In Le Tibet révolté, Bacot noted that he was granted permission from the Vajradhara Drakkar, also known as the “Tchraker lama,” to take photographs of him. Bacot was asked by lamas accompanying the Vajradhara Drakkar to send them copies of this photographic image (par), which could then be transformed into an object of consecrated power (rten). As a gift to exchange with the photographic copies, Bacot was given “magic pills” or “precious pills” (rin chen ril bu) by the lama. Although Bacot called this revered and authoritative tantric figure a “living Buddha,” he specified in a journal footnote that he was an earthly emanation of Avalokiteshvara or Chenrezig.

Bacot’s narrative of this encounter was strikingly polyphonic: he first recounted his own interviews with the lama and the lama’s inquiries about the Frenchman’s travels to India. He simultaneously reported the bewildered questions that the lama asked Adrup Gönpo about his travels to France “beyond the ocean,” “on the edges of the world.” While still in Tchangou, he then saw firsthand a medium lama (sku bdon pa) in a trance, and upon giving a vivid account of the event, concluded that the experience was sincere and noteworthy: “No other religion can move the most indifferent spectator, and thus throw them away from their familiar sphere into this hazy confusion that is the threshold of the unknowable.”

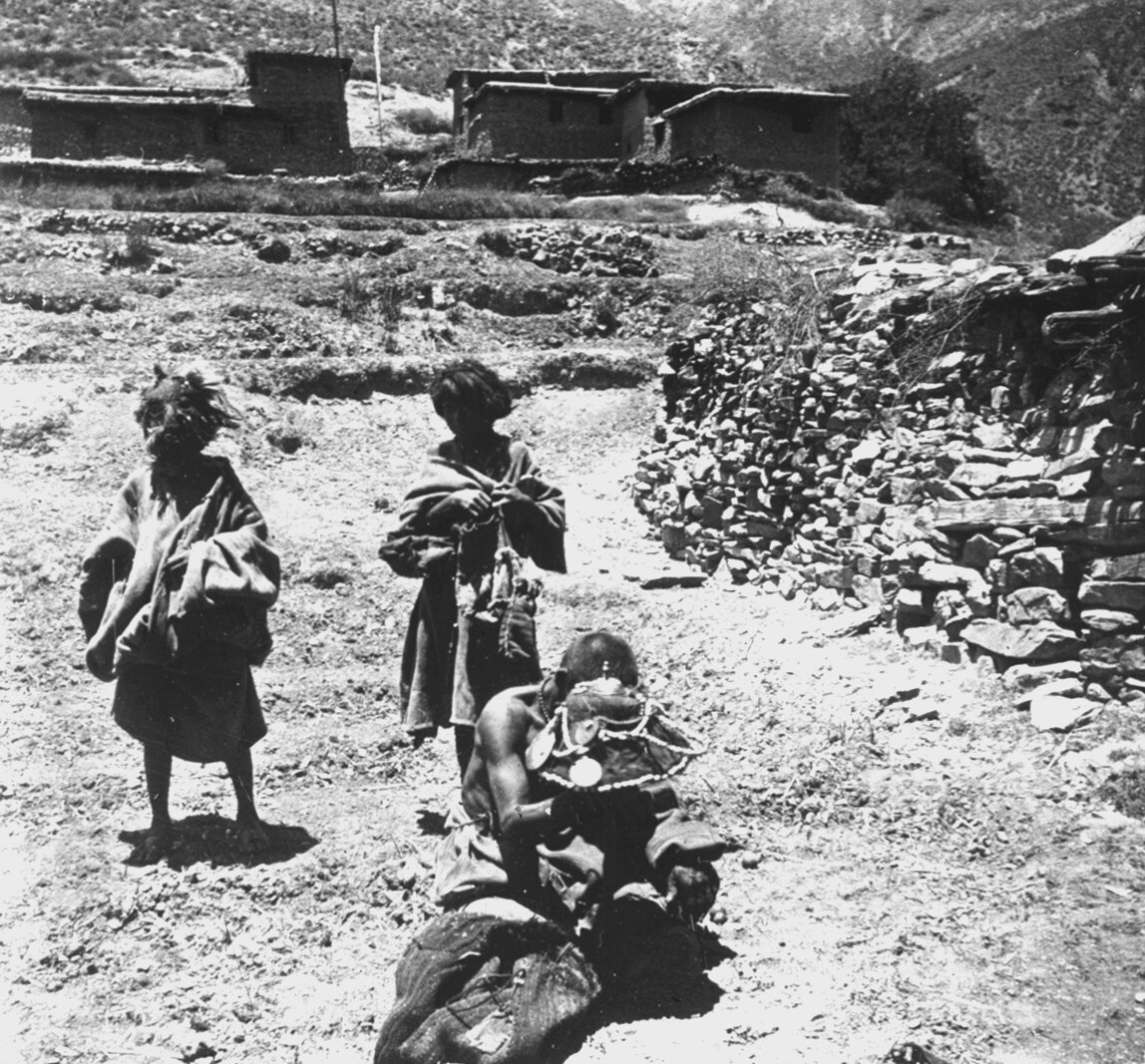

Maṇi pa and two children in Kham, 1907. Jacques Bacot photographic collection.

© École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

One major, unexpected event completely altered the direction of Bacot’s travels and provided him with a unique experience of Tibet. Following a group villagers and pilgrims, he set out for an unmapped area that was referred to as the “hidden valley” (sbas yul) of “Népémakö” (Gnas Padma bkod). It was rumored to have been revealed to the Tibetan people centuries ago by Guru Rinpoche, or Padmasambhava, the spiritual father of Tibet. This “promised land,” as he called Népémakö, was located southwest beyond Poyul, another region he was still looking for. Although Bacot eventually had to abandon the trip, his own idea of exploration had accrued renewed meaning, since his attempted discovery of the place was no longer confined to the explorer’s empirical quest for “virgin” or untrodden places. Instead, it extended to the mythical topography of Tibet maintained by the Tibetans themselves, and to a specific cultural tradition on Tibetan terms and previously unknown to Europeans.

Before his return to France in early 1910, Bacot sojourned in Patong, Adrup Gönpo’s hometown, for three months. There he collected and had copies made of Tibetan and Mosuo texts. He also improved his knowledge of Tibetan language, writing, and culture under the supervision of Senan Temba, who was Adrup’s uncle and a Nyingma lama.

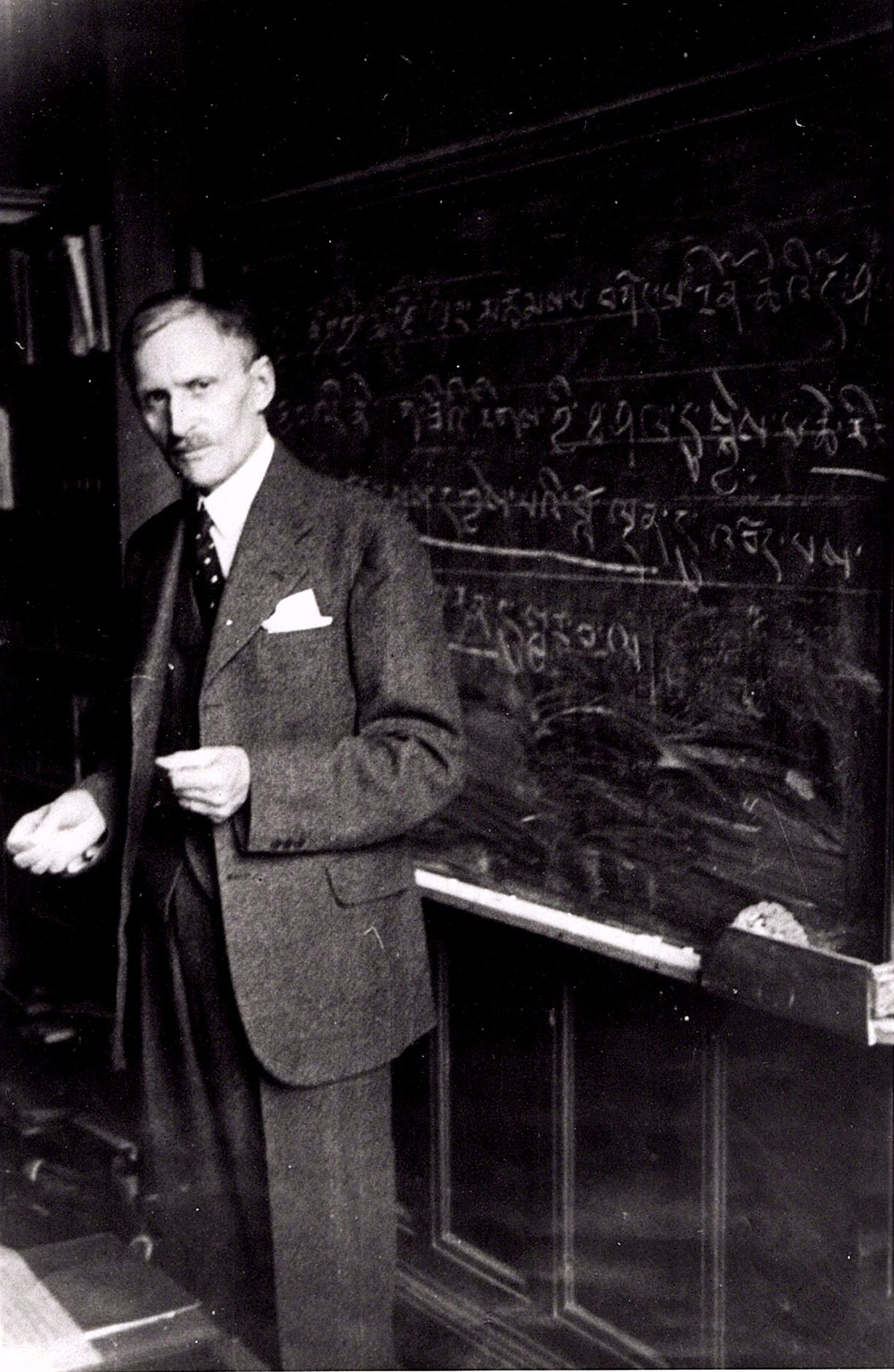

Jacques Bacot teaching Tibetan at the École pratique des

hautes études in Paris, 1938. Paper print photograph by

Yu Daw-chuan. © Private collection of Olivier de Bernon

Bacot was not the first Tibetologist in France. However, he most certainly changed the direction of how Tibetan studies was taught and learned. Tibetology already enjoyed a celebrated scholarly legacy that dated all the way back to 1842, at the École des langues orientales vivantes in Paris. This was the year Philippe-Édouard Foucaux was appointed the first official professor of Tibetan in Europe. In contrast, when Bacot left for Asia, he had no university education. While he acquired some methodological training from scholars in geography, anthropology, and philology in 1906 and 1908 in Paris, he clearly developed his professional skills outside of the academy and was much more of a hands-on learner on the field.

From as early on as 1911, Bacot built on his experience of Tibet by becoming a teacher of the Tibetan language at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris. His pedagogical style followed in the footsteps of the famous Indianist Sylvain Lévi (1863–1935), with his lessons on Tibetan literature similar to Lévi’s classes on Buddhist Indian texts. In 1936, Bacot was appointed professor (directeur d’études) of the École’s new chair of Tibetan studies. In his numerous and authoritative publications and teachings, Bacot demonstrated an extensive knowledge of Tibetan language, culture, and history, from cursive writing and grammar to divination, from ethnography to imperial history, and from old Dunhuang documents to art and literary traditions such as biography, letter writing, and drama.

Actors coming on stage in Garthar (Mgar thar མགར་ཐར་།), Kham, July 1909.

Jacques Bacot photographic collection. © École française d’Extrême-Orient (Paris)

In his work, Bacot listed the names of several lamas and Tibetan contributors who, like Adrup Gönpo, had come to France from 1912 onwards, or with whom he worked while in Kham, Darjeeling, or Kalimpong. Even in the publications of his latter years, Bacot kept a vivid memory of his early 20th century travels. In his writing was a discernible political and cultural concern for the fate of Tibet and an enduring passion for the promotion of Tibetan culture. For example, in his introduction to his translation of Zugiñima (Gzugs gi nyi ma, “Sun of Beauty”) in 1957, Bacot clearly referred to his first impressions of Tibetan theatrics in Gata (Mgar thar) in Kham: “Tibetan theater is designed for wide open-air stages” and in it, “art and plot serve a remarkable sense of emotional uplifting.” Therefore, “as such, they deserve to step outside the narrow boundaries of philology.”

In his translation works, starting with Three Tibetan Mystery Plays in 1921, the accounts of the lives of Milarépa (1925) and Marpa (1937), and then his biography of the Buddha (1947), Bacot reconnected, time and again, with his own lived experience of Tibet. He never forgot that formative journey.

To be continued in part three.

See more

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Jacques Bacot’s Rebel Tibet, Part One: Early 20th Century Travels to Kham

Jacques Bacot's Rebel Tibet, Part Three: Buddhism in Interwar and Postwar France

Tibet on the Silk Road from a Curator’s Eye: An Exhibition Tour with Dr. David Pritzker

Monklife

Who was Alexandra David-Neel? A Brief Story of a Buddhist Anarchist

Freda Bedi: The Making of a Buddhist Nun

Candid Amdo