It has been literally years since I watched a documentary and thought it was objectively good (liking it or disliking it is a subjective thing), because too often documentaries about the humanities like history, religion, or the arts push only the director or writer’s perspective, seeking to explain rather than enlighten. But how can a film enlighten us about something without explaining it? KanZeOn, which was the opening film of this year’s Zipangu Festival, shows us how, since in this documentary there is no narrative on part of the co-directors (Neil Cantwell and Tim Grabham). Instead, the documentary is designed to immerse its watchers in the stimuli of nature, Buddhism, sounds and visuals. According to its description, KanZeOn takes “the viewer on a hypnotic sensual journey from the timeless to the modern by way of a mystical parade of images that resonate seamlessly with the sounds.” I must say that such a synopsis actually does good justice to what

FEATURES|THEMES|Art and Archaeology

KanZeOn: A Documentary on Sound

Buddhistdoor Global | 2011-12-03 |

the documentary achieves. KanZeOn also describes itself as “a mystical journey from the timeless to the modern looking at the role of sound in Japanese Buddhism.”

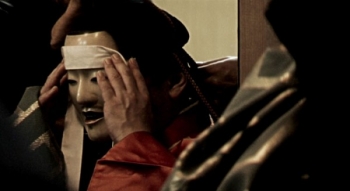

Obviously, KanZeOn is little more than a quirky spelling of the alternative name (Kanzeon) for the Bodhisattva of Compassion as she is known in Japan, Kannon, or Guan Yin in China. The name is significant because in traditional Indian Mah?y?na Buddhism, the bodhisattva’s compassion is centred around his omnipresent sight (Avalokite?vara means the Lord Who Looks Down), whilst in East Asia she reveals her love for the cosmos by hearing all our cries. It is this emphasis on “seeing sound” that inspires this documentary. Filmed in Kyushu, the film centres on the spiritual and musical lives of three unique Japanese musicians. They are Akinobu Tatsumi, the young Buddhist priest and custodian of a temple outside of Kumamoto City. He is also an extremely talented hip-hop DJ, indulging his love of beatboxing in the remote forests and groves that inspire him. Then, from the Shinto perspective, there is the priestess Eri Fujii, who has devoted her life to the mastery of the sho. Finally, Akihiro Itomi is a master of Noh theatre and a kotsuzumi drum player who loves Western jazz as much as Japan’s traditional performing arts.

KanZeOn is at once relaxing and intense, mild and powerful. One can be relaxed while watching it, but surprisingly intense concentration is drawn from you at the scenes of nature. Instead of a conventional documentary narrative (in the style of Sir David Attenborough, for example), KanZeOn is more of a “meditation” on sound and the religious role it plays: Dr. Lucia Dolce of SOAS, who was present at the screening, rightly said it had strong Buddhist undertones from the beginning. Indeed, it opens with a tranquil, haunting ceremony at Tatsumi’s temple, although there are far less sombre scenes interspersed throughout the movie, such as the priest introducing hip-hop to his congregation of elderly women, or beatboxing in the middle of a staggeringly high bridge over a river in a forest. It really is quite stunning.

The sho is a rare and ancient bamboo wind instrument that, according to legend, was made by a man who ascended to a celestial realm and heard a Chinese phoenix’s cry. After returning to the mortal world, he constructed an instrument that came as close as possible to mimicking it. This myth highlights Eri Fujii’s belief that sound is not made: we invoke sound and then play with it to make music. Sound and music are the same, and anything in nature can be music, from the crash of waterfalls to the chirping of birds. In contrast to the lovely Shinto stories told by Eri Fujii, Itomi emphasizes Noh as being a blend of Indian and Chinese music, and fundamentally Buddhist despite being based on indigenous deities. The whole point of the orally transmitted tradition, which requires absolute passion and commitment on part of its heirs, is to save the suffering gods by means of Buddhism. Without Buddhism there is no Noh. Adding to the movie’s Buddhist flavour is the cameo of Shingon University at Kyoto, at which Neil Cantwell is a research fellow. Mantras and mandalas are taught in the academic curriculum, and the invocation of certain sounds can bring about certain effects. Brought together, the spiritual lives of the University, Itomi, Fujii and Tatsumi sing of a constellation of musical traditions (including beatboxing!) that all have found a home in the Buddhism of Japan: ever-changing and malleable, but forever centred on saving suffering beings, even Shinto gods.

It would be difficult to come across a documentary quite like KanZeOn. This is only natural, I suppose: where else can you learn about a temple DJ monk, a sho musician and a Noh master all in one program? I’m very wary of Western media presentations about our East Asian cultures because they too often perpetuate Orientalist stereotypes that have damaging consequences in real life. But because the British filmmakers literally don’t speak, and let the film’s subjects speak for their own lives, my worry was unfounded here. KanZeOn is an excellent Buddhist documentary and should be watched by all interested in Buddhist culture.

Categories:

Comments:

Share your thoughts: