FEATURES|COLUMNS|Exploring Chinese Buddhism

Looking for the Pure Land: A Visit to Xuanzhong Monastery

According to the major sutras of Pure Land Buddhism, the Larger Sukhavativyuha and the Smaller Sukhavativyuha, Amitabha Buddha’s Pure Land (Skt. Sukhavati) lies beyond 10 billion Buddha-lands west of our World of Endurance. Having been fully developed from the mid-6th to the early 9th centuries, the belief in rebirth in such a place and the recitation of Amitabha’s name to achieve this goal became central to Pure Land Buddhism, serving as an expedient for the meditative path to enlightenment or even as a method of equal importance since the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). To better understand the nature of the Pure Land and how it is related to the world in which we sentient beings live, I visited one of the birthplaces of Pure Land Buddhism—Xuanzhong Monastery (玄中寺) in Jiaocheng County, Shanxi Province, China.

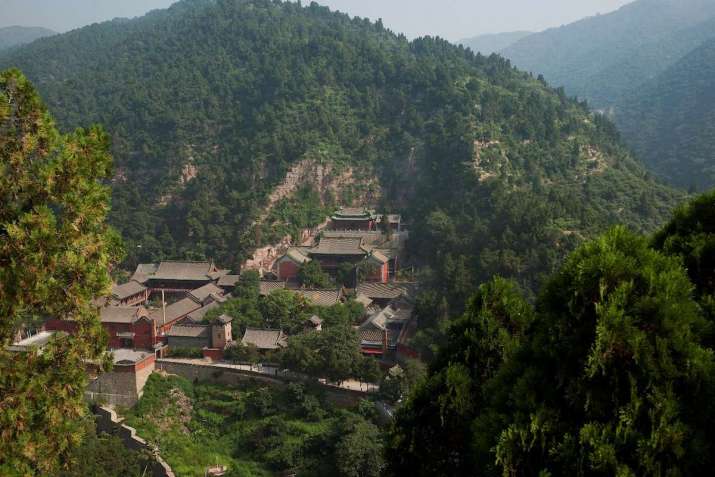

Since its establishment in 472, Xuanzhong Monastery has stood on the same site in the Shibi Mountains, remote and secluded. Three patriarchs of the Pure Land school, Tan Luan (曇鸞, 476–542), Dao Chuo (道綽, 562–645), and Shan Dao (善導, 613–81), resided and spread the teachings there. For this reason, Xuanzhong Monastery received continuous imperial patronage during the Tang dynasty (618–907). When Kublai Khan ruled China, he also granted the monastery imperial protection. Khan’s edict, inscribed in stone in both Chinese and the ‘Phags-pa script,* has been well preserved in the monastery’s stele collection. Today, Xuanzhong Monastery is lauded as an ancestral court by Pure Land Buddhists in China, as well as by followers of Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu—two Pure Land sects in Japan.

Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang Liquan

Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang LiquanDuring my stay at Xuanzhong Monastery, I was warmly received by Venerable Wufeng (悟峰). He has been the acting abbot since the passing of the former abbot Venerable Master Gentong (根通, 1928–2015), who was born in Guandong Province, and later became an influential Buddhist leader in Shanxi Province and the seventh vice director of the Chinese Buddhist Association. Venerable Wufeng is from Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. In his teens, his interest in Buddhism was ignited by the 1982 film The Shaolin Temple, and he was determined to become a kung fu master to benefit the world. However, during his initial monastic life at the Shaolin Temple, Venerable Wufeng realized that his desire to learn kung fu was driven by fame and self-interest, and he became convinced that true happiness and perfection cannot be achieved by combat, but rather, by wisdom.

Venerable Wufeng speaking at a life-release ceremony. Image courtesy of Xuanzhong Monastery

Venerable Wufeng speaking at a life-release ceremony. Image courtesy of Xuanzhong MonasteryNowadays, success is usually measured by action and tangible outcome. For those unfamiliar with Buddhism, it may be difficult to comprehend how the monastic sangha can contribute to the world while choosing to withdraw from it. “It is true that at the turn of the 20th century—a time of turmoil in China—many sangha members either focused on self-cultivation or on performing rituals for the dead,” Venerable Wufeng explained. “As a response, Venerable Master Taixu (1890–1947) pioneered the idea of Humanistic Buddhism, calling on sangha members to construct a Pure Land on Earth by engaging with society, integrating Buddhist teachings into everyday life, and guiding people in good conduct, mind purification, and spiritual cultivation.”

This effort to build a Pure Land on Earth is in every way compatible with faith in Amitabha’s Pure Land. While clearing defilements from their minds and from this world, Pure Land Buddhists long for an even better place—a perfect and magnificent realm free of suffering. On the surface, Amitabha’s Pure Land in Mahayana Buddhism and Heaven in Christianity may sound similar: both are of a metaphorical nature, describing a state of consciousness or condition of existence. Nevertheless, they reflect two fundamentally different tenets of cosmology and soteriology. “For instance,” Venerable Wufeng clarified, “in Buddhism, heaven is yet found in the six realms of samsara, but Pure Land is beyond that, transcending the cycle of rebirth. Moreover, in the Christian Heaven, each being is a subject of God, while in the Buddhist Pure Land, each being becomes a Buddha themselves, possessing the same virtue and capacity as the Buddha.”

On one hand, the path to Amitabha’s Pure Land lies in the merit gained from this life and our past lives. On the other, as Venerable Wufeng elucidates, the vision of Amitabha’s Pure Land makes us less attached to this world. In the Buddhist view, all wars and killing originate from nothing but human selfishness. Venerable Wufeng commented, “Kings and warriors are heroes because they conquer others. The members of the Buddhist sangha are sages because they conquer themselves. They are masters of their own minds, so they are able to spread wisdom and compassion, benefiting others in a selfless way.” Indeed, since the beginning of the 20th century, Xuanzhong Monastery has played an instrumental role in Sino-Japan relations. During the Second World War, Venerable Ekei Sugawara (菅原恵慶), a Pure Land master from Japan, traveled to Xuanzhong Monastery to pay homage. Having devoted the rest of his life to the research and promotion of Pure Land Buddhism, his ashes were buried at Xuanzhong Monastery at his request. This gesture was not just a religious statement, but also one for world peace.

Venerable Wufeng and members of the Japanese Association for Xuanzhong Monastery Worship (日本玄中寺奉赞会) in 2015. Image courtesy of Xuanzhong Monastery

Venerable Wufeng and members of the Japanese Association for Xuanzhong Monastery Worship (日本玄中寺奉赞会) in 2015. Image courtesy of Xuanzhong MonasteryChinese Buddhism developed the concept of various Pure Lands, such as Maitreya’s Tusita, Bhaisajyaguru’s Vaiduryanirbhasa, and Vairocana’s Padmagarbha, all expressing a general goal of rebirth in an ideal place. However, Amitabha’s Pure Land became the most popular, thanks to the nianfo (念佛), the method of reciting Amitabha’s name devised by the Pure Land school patriarchs. It is so approachable that even the least enlightened person can recite “Namo Amituofo” for salvation anytime and anywhere. Today, “Amituofo” has become a greeting among Buddhists in China, regardless of the Buddhist tradition one is affiliated with. You could be facing a layman, a Chan master, or even a Tibetan lama, and as soon as you start a conversation with “Amituofo” and joined palms, you already have their goodwill and trust.

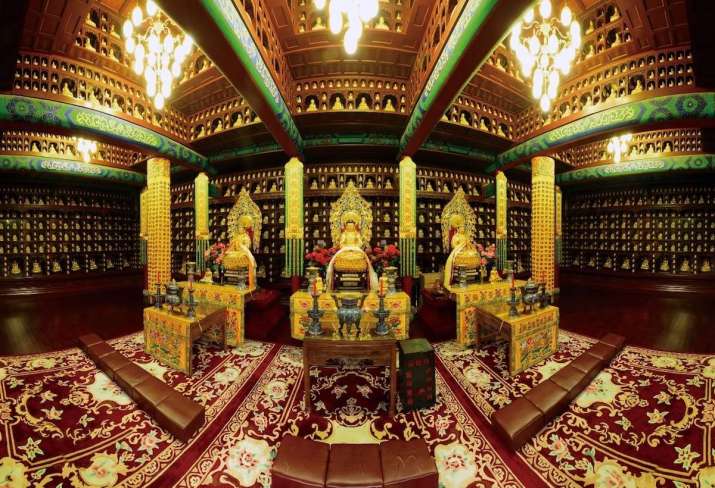

Hall of Ten Thousand Buddhas at Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang Liquan

Hall of Ten Thousand Buddhas at Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang Liquan“Reciting the name of Amitabha can be compared to using a point-and-shoot camera. It looks simple, but it has all the necessary functions. This method is like a small spring, and ultimately it flows into the ocean of Buddhist teachings”, Venerable Wufeng explained to me. Apart from merely reciting Amitabha’s name, there are another three nianfo methods for people of different meditative and spiritual capacities, namely reciting the name of Amitabha in front of his image, reciting the name of Amitabha while visualizing his image, and reciting the ultimate essence of Amitabha.** According to Venerable Wufeng, in the practice of the last nianfo method, one experiences the merging of Amitabha’s name being recited and the mind that recites Amitabha’s name. He elaborated: “If Amitabha’s name is snow, the ultimate essence of Amitabha is water, as snow melts into water; if Amitabha’s name is floating clouds, the ultimate essence of Amitabha is void, as clouds disappear into the void. Through this method, one sees Buddha nature (Skt. tathagatagarbha) and the Buddha’s true body (Skt. dharmakaya). The method itself is Chan, is esoteric knowledge.”

Contemporary wall painting in the Hall of the Patriarchs at Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang Liquan

Contemporary wall painting in the Hall of the Patriarchs at Xuanzhong Monastery. Photo by Yang Liquan* The script was designed by Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, the fifth leader of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism and the imperial preceptor under Khan’s rule.

** See Wufeng, “Xuanzhong Monastery and Pure Land Buddhism,” (The Buddhist Association of China)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Determinant Faith of the Three Pure Land Sutras

Book Review: Approaching Buddhism—An Introduction to the Buddhist Tradition from the Pure Land Perspective

The Buddhism of Forks or Chopsticks

The Potential of Propagating Pure Land Buddhism in the West