FEATURES|THEMES|Books and Literature

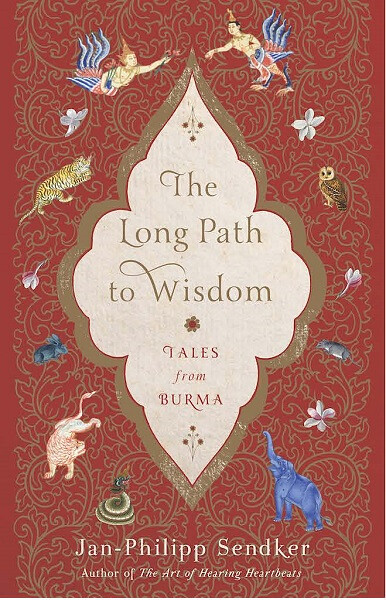

Lore and Magic from the Straw Hut—The Long Path to Wisdom: Tales from Burma

There is an intangible thread connecting the Myanmar of hyper-change, capitalism, and military rule with the Old Burma of magic disturbances, quirky animals, unresolved tragedies, and busted secrets. With The Long Path to Wisdom we are wandering in the realm of the latter—a land of living marionettes that teach their owner what truly matters in life, a hare that works as an impartial judge, of cranky monks, kind merchants, and lovesick princesses. As Sendker himself confesses in his opening essay in the book, “My Burma,” some of these tales shocked and depressed him. Not a few of these tales are fatalistic, or at least paint a picture of the world that is indifferent to protagonists and antagonists alike.

“The Little Boy and His Tiger,” the very first story, establishes this tone right away, with (spoiler alert) no one coming out of it particularly well despite all understandably having self-interested motivations. “The Flood,” a story of two children murdered by a fishing mob and a grandmother’s grief, is flat out miserable. “The Starving Orphans,” in which two siblings starve to death without each other’s company and are reborn as little birds, is heartbreaking. Sendker writes that the “dismal sorrow” of these tales remind him of the sad endings in Hans Christian Andersen’s tales like “Little Match Girl.”

Sendker presents an enchanted and exciting but unforgiving landscape that should resonate with those familiar with the tales of the Grimm brothers and contemporary pop culture circles. As we have seen with fantasy novels like A Song of Ice and Fire, its HBO adaptation Game of Thrones, and video games like The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, readers want nuance and thought-provoking arcs, and do not demand that good characters always enjoy a happy ending. This is not to say that despair and cynicism is in vogue, but that sometimes ambiguous or even bad endings have as much to teach us as good ones.

Yet there are some stories that mix the mystic with the moral, seeming more recognizable as fables with something a lesson or ethical instruction that one can take away. “The Little Snail” is all about diligence and never giving up, while “The Long Journey” assures good things to those who keep their promises. “A Pious Queen” depicts a would-be murderer shamed into defeat by graciousness and forgiveness. And there are those tales that are straightforward in their good-heartedness: avatars of innocence, usually children, abandoned by figures of trust and pursued by murderous creatures, before being saved by a benevolent, powerful force like a magical dragon. “Nan Ying and Her Little Brother,” one of my favourites from the collection, belongs to this sub-genre.

Jan-Philipp Sendker. From simonandschuster.com

Jan-Philipp Sendker. From simonandschuster.comThere is another informal category of the Burmese tales that I find to be straight-up comedy. Some of the stories in this collection are the funniest I have ever read in world mythology. “The Village of Endless Sermons” seems to be a caution against overweening piety, or at least pokes fun at people who like to show off their propensity for listening to long sermons. “Three Women and One Men” is a long and complicated yarn about why one woman might deserve a prospective husband more than the other, but the way it articulates its simple message is uproariously fun, as we follow our protagonist’s encounters with more than three other women in compromising circumstances.

Finally, what would an anthology be without bittersweet, melancholic fables? “The White Crow and Love”—an account of a prince, his beloved naga princess, and a crow whose error causes a major calamity— perfectly captures the nature of bad timing, of lives ruined and opportunities for happiness denied by a momentary mistake or misunderstanding. Not everything in life can be resolved: it is too late for the prince to correct the misunderstanding that caused the naga princess to leave the human world in anguish. Yet the regret of a broken promise becomes motivation to honor the memory of possibilities lost.

“The Grateful Serpent” tells the story of a girl, who has known only abuse and loneliness, finding happiness under the care of an old, kind hermit. Murdered in the forest by thieves, she is reborn as a python because of her last moments of feeling hatred and vengeance. This tragedy becomes a story of healing as the python searches for the deceased hermit’s reincarnated form, a monk in a distant temple. The python’s reunion with the monk and her peaceful residence at his monastery (along with the blessings that follow) is a deeply moving resolution. There is no revenge, no justice served. Just a journey concluded, and two lives reunited.

The Long Path to Wisdom is universal in the sense that its tales speak of universal human themes: love, faith, greed, trust, betrayal, and forgiveness. It is a world anyone would recognize, and Sendker’s book is therefore accessible to all. Yet it retains a unique, distinctly Burmese touch: a world of ambiguity, of living spirits influenced by the Buddhist presence in Old Burma, and feelings of longing echoing over many lifetimes.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Literature as a Way of Living, Part One

Literature as a Way of Living, Part Two

Related blog posts from Buddhistdoor Global