FEATURES|COLUMNS|Exploring Chinese Buddhism

Love Carved in Stone: Appreciating Buddhist Art in a Non-Buddhist Way

At the Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum in Hong Kong, there is a limestone sculpture depicting a pair of hands holding a cylindrical object. At first appearance, there is nothing Buddhist about the hands. They bear no Buddhist symbols or attributes. However, the mystery amplifies the charm of the sculpture, which has drawn countless visitors to stop, behold, and wonder: Whose hands are these? What is he or she holding? When was this sculpture made?

Hands of a Disciple, China, Northern Qi dynasty, Tianbao reign (550-59). Limestone, height 36 cm. Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum

Hands of a Disciple, China, Northern Qi dynasty, Tianbao reign (550-59). Limestone, height 36 cm. Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art MuseumThe sculptural form of the hands is human and rhythmic, and the surface has a warm and softly polished patina. The visual aspects and aesthetics are reminiscent of British modern sculptures, which are best known for biomorphic abstraction. Biomorph is a compound of the Greek roots bios (life) and morphē (form). Biomorphic sculptures are abstract but evoke living forms such as plants and the human body. One of the most quintessential examples is Recumbent Figure 1938 by Henry Moore (1898–1986), which depicts a reclining female figure. Originally commissioned as a site-specific sculpture for the grounds of a house in Sussex, the undulating and organic form, according to Henry Moore himself, was to add “a humanizing element” and to become a “mediator” between the rolling hills and the modern architecture.*

Recumbent Figure 1938, Henry Moore. Green Hornton limestone, 88.9 × 132.7 × 73.7 cm. Tate.

Recumbent Figure 1938, Henry Moore. Green Hornton limestone, 88.9 × 132.7 × 73.7 cm. Tate.The stone hands at the Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum are clearly representational, but somewhat stylized and idealized as there are no signs of gender, age, or cultural identity. Nevertheless, onlookers of diverse backgrounds can appreciate a sense of protection, loving care, and devotion. Such emotive and perhaps spiritual qualities can also be found in Barbara Hepworth’s (1903–75) Mother and Child 1934. Carved in separate pieces, the “mother” embraces and supports the “child.” It may represent a life-giving force, as if the child emerges from the mother’s womb. At the time of creating this work, Hepworth was pregnant with what turned out to be triplets. Her experience of being a woman and mother was definitely translated into divine femininity in her oeuvre. Like her male contemporaries, Hepworth practiced the hard labor of carving native stone by hand, but her works consistently exhibit a unique sensitivity and grace.

Mother and Child 1934, Barbara Hepworth. Pink Ancaster stone,

26 × 31 × 22 cm. Photo by Jerry Hardman-Jones.

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

In Buddhist discourse, the metaphor of parents and children is often used to express love that is unconditional and selfless. As Chan Master Thich Nhat Hanh articulates, the four elements of true love are loving-kindness (Skt: maitrī), compassion (karuṇā), empathetic joy (muditā), and inclusiveness (upekṣā).** To love requires a deep understanding of human suffering and of the interdependence of all sentient beings. There is a remarkable resemblance between the way the Tsz Shan hands hold the mysterious object and the way Hepworth’s mother holds the child. Both are affectionate and tender, emanating love and timeless beauty.

Hands of a Disciple, China, Northern Qi dynasty, Tianbao reign (550-59). Limestone, height 36 cm. Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum

Hands of a Disciple, China, Northern Qi dynasty, Tianbao reign (550-59). Limestone, height 36 cm. Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art MuseumHowever, let us not forget that the Tsz Shan hands, unlike modern British sculptures, were not made as a stand-alone artwork. Rough chisel marks on the rear of the hands indicate that the sculpture was cut away from its original context. Recent research at the University of Chicago has discovered that the hands came from the Middle Cave of the North Site of Xiangtangshan (Mountain of Echoing Halls), a complex of Buddhist caves in Hebei Province, northern China. Dating to the Tianbao period (550–59) of the Northern Qi dynasty, the pair of hands belonged to a statue of Mahākāśyapa, one of the chief disciples of the Buddha. In fact, after the passing of the Buddha, Mahākāśyapa headed the monastic community and presided over the first Buddhist council. In Chinese Buddhism, Mahākāśyapa is also lauded as the first patriarch of the Chan school.

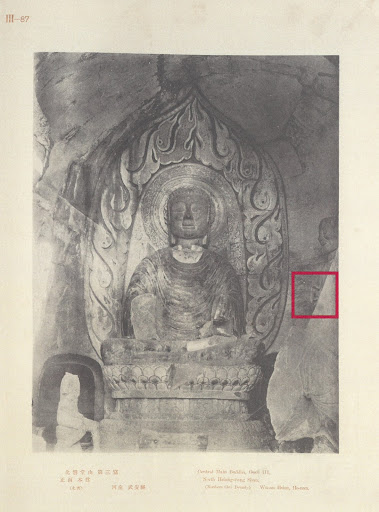

Middle Cave, North Site, Xiangtangshan Caves, Hebei Province, China. From xts.uchicago.edu

Middle Cave, North Site, Xiangtangshan Caves, Hebei Province, China. From xts.uchicago.edu

Tokiwa Daijō and Sekino Tadashi, Shina bukkyō shiseki

[Buddhist Monuments in China], (Tokyo: Bukkyō

shiseki kenkyu-kai, 1924–31), vol. 3, plate 87

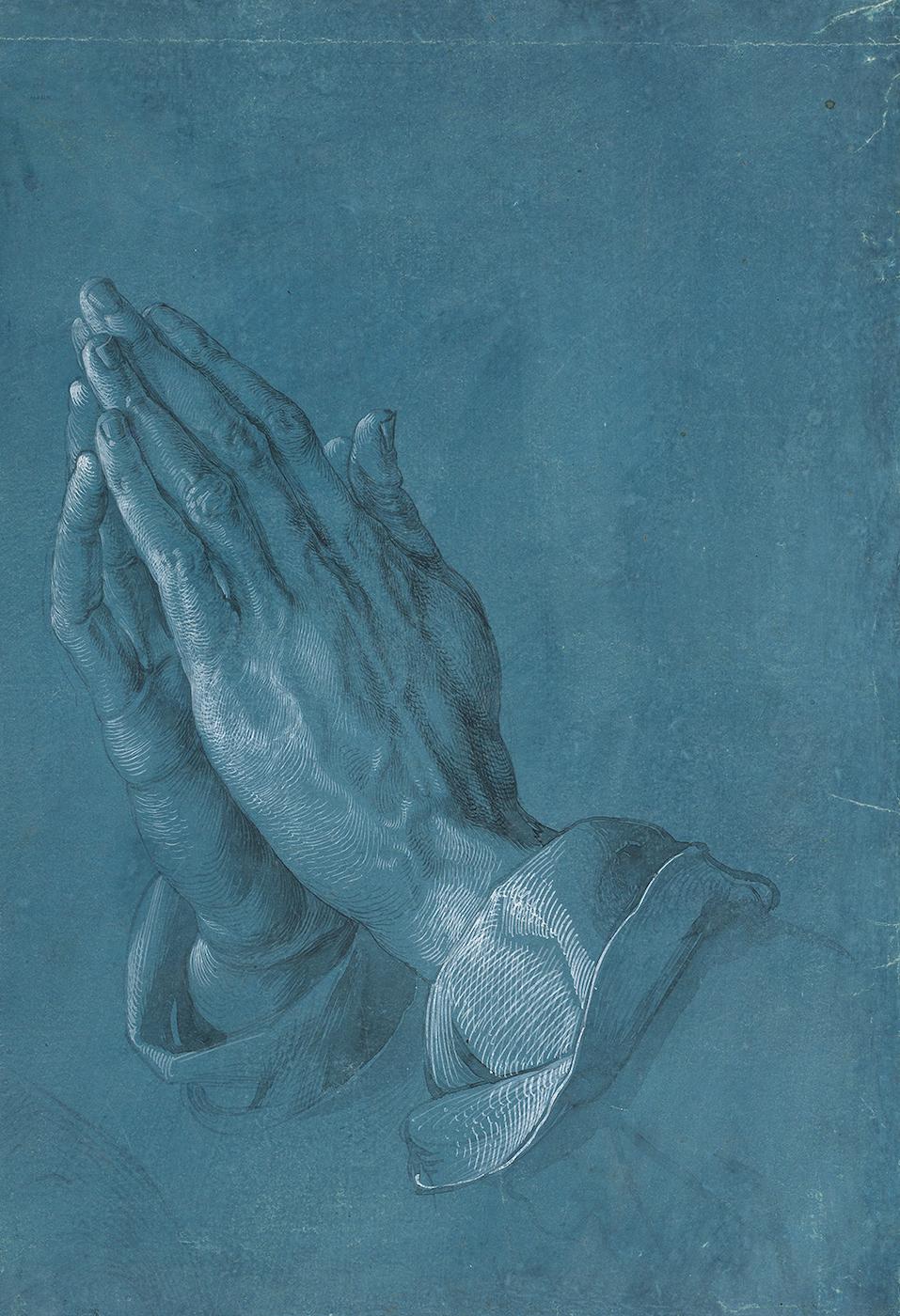

In terms of religious significance, the hands of Mahākāśyapa can be compared with Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). A preparatory drawing for a triptych titled the Heller Altarpiece destroyed by a fire in 1729, or a virtuoso work in its own right, as contested of late, Praying Hands has become a hugely popular icon of Christian art in Europe, symbolizing veneration and love for God.*** But why were the hands of Mahākāśyapa removed from a sacred Buddhist altarpiece? At the beginning of the 20th century, China was in a state of political turmoil. Many Buddhist sites, Xiangtangshan included, were plundered to satisfy the growing art market in the West and in Japan. While most looters coveted whole figures or heads of monumental statues, someone, unlikely a Buddhist, was captivated by the sheer visual allure of the hands. The act of pillage is indeed questionable, but the looter’s eye for good art is certain.

Praying Hands, Albrecht Dürer, 1508. Ink and pencil on paper,

29 x 19 cm. The Albertina Museum, Vienna

The North Site of Xiangtangshan, where the Tsz Shan hands originated, was imperially sponsored, thus the hands represent the craftsmanship par excellence of the Northern Qi dynasty. The artist who carved the hands in sixth century China would have had no less talent than Dürer in 16th century Germany or Moore in 20th century England. Nevertheless, the master sculptor remains nameless in history, as is usually the case in the tradition of Buddhist art. The purpose of making Buddhist art is not self-expression or secular success, but for elevating spirituality and accumulating merit that will ultimately lead to liberation from the cycle of rebirth. In his last years of life, Moore suffered from illness and made many drawings of his own hands. He remarked:

After the head and face, hands are the most expressive part of the human body.

Hands can convey so much—they can beg or refuse, take or give, be open or clenched, show content or anxiety. They can be young or old, beautiful or deformed. . . .

Throughout the history of sculpture and painting one can find that artists have shown through the hands the feelings they wished to represent. Rembrandt, for example, uses hands to express nearly as much as the head and its features.

The nearest model is one’s own hands. . . .****

From these words, we may be able to glimpse the artistic and creative mind behind the hands at the Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum. Some scholars suggest that the hands are holding a reliquary to contain a share of the Buddha’s relics, while visitors of different cultural or religious backgrounds have their own imagination: a box, a light, or a gift. The pair of hands carved in stone by an obscure artist 1,500 years ago continues to evoke loving-kindness, compassion, joy, and inclusiveness among beholders. They are imbued with love and radiate love. Indeed, it is a shame that the hands were uprooted from their original setting, however, it is also fortuitous that such detachment has opened up infinite possibilities.

* Henry Moore in Sculpture in the Open Air, British Council film, 1955, transcript reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.258–9.

** See Thich Nhat Hanh’s work How To Love. The four elements, in Chinese 慈悲喜捨, comprise the Buddhist concept of the “Four Immeasurables” (brahmavihāra, 四無量心所). By cultivating these virtues, one can improve wellbeing and achieve the highest spiritual state.

*** Since April 2020, I have been exploring artistic and conceptual similarities between Buddhist art and Western art. The findings have been uplifting, and I plan to share more in my writings.

**** Quoted in Nicholas Robins and Robert Robins, “Hands and the artist — Henry Moore”, in The Journal of Hand Surgery: British & European Volume. Vol. 12, issue 1, 1987, pp. 140–43.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Human Connection: Retired Catholic Priests and a Chinese Buddhist Monk

Zhiguan Museum of Fine Art: Strengthening the International Community of Himalayan Art

A Journey Through 5,000 Years of Tibetan History and Culture at the Capital Museum in Beijing