FEATURES|THEMES|Art and Archaeology

Love Story in a Buddhist Cave: The Grottoes of Maijishan

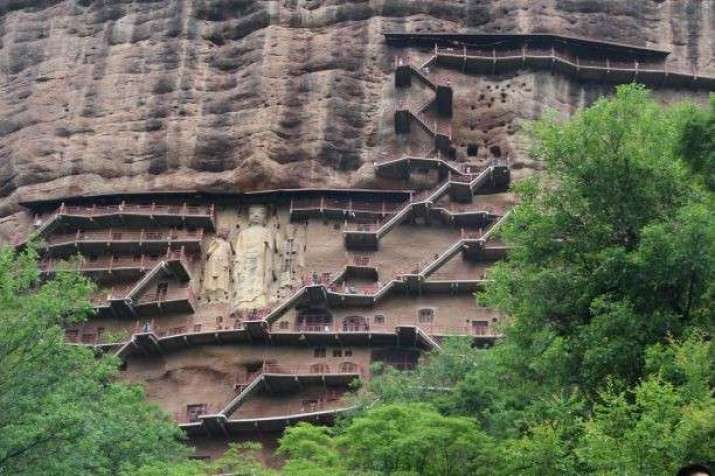

The Maijishan Grottoes. Image courtesy of the author

The Maijishan Grottoes. Image courtesy of the authorHui Ying Gigi decided to dedicate herself to promoting Buddhist art after a trip to the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, China. She is a docent for Tsz Shan Monastery Buddhist Art Museum and was interviewed by Hong Kong's Viutv to introduce the museum’s Buddhist art collection. Gigi earned a distinction in her Master of Buddhist Studies at the University of Hong Kong with her thesis, “Beauty of the Buddha’s Smile.” Her paper compared the facial proportions of Buddha statues to traditional and modern standards of beauty to explore the aesthetic of the Buddha’s smile. Gigi plans to further her studies in Buddhist art at SOAS University of London in 2021. Ultimately, she hopes to earn a PhD in Buddhist art.

Once upon a time, as they say, there was a kingdom in northern China. The king and queen enjoyed a happy marriage for 13 years. The queen was famous for her modesty, and this made the king love her even more. The queen was pregnant every year, but only two princes survived. The king did not hold true power in the kingdom, which actually rested in the hands of one of his generals. Since the kingdom was constantly being attacked at its borders, the general forced the king to marry a princess from a neighboring invader to make peace with the border tribes. Reluctantly, the king dethroned his queen and forced her to become a nun to legitimize his marriage to the princess. However, the princess was not satisfied and was overwhelmed with jealousy by the king’s love for the queen. She demanded the outright death of the former queen and helped raiders to launch another attack at the border, threatening the kingdom. The king, believing he had no choice, sentenced the former queen to death. Although she was already a nun, she committed suicide to bring peace to the kingdom.

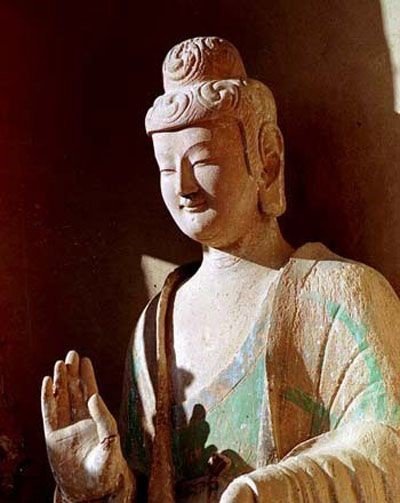

This queen-turned-nun did not receive a royal burial, instead she was buried in a Buddhist cave. This cave, No. 43 in the Maijishan Grottoes, is her tomb, and another cave next to her tomb was carved out by her son to honor her. It is said that the Buddha statue enshrined in this cave bears the face of the queen. Indeed, the Buddha image in this cave does carry a hint of femininity—the aesthetic flair seems to invoke a middle aged woman, with a smile full of motherly love. The smile appears to be very natural and humanistic, like an Asian version of the Mona Lisa. Many cave temples follow this feminine presentation of the Buddha, which is called the “Yifu style,” named after the queen.

Maijishan, or Mount Maiji, is located in Gansu Province in northwest China, some 70 kilometers southeast of Tianshui. The name Maiji, which means “wheat stack,” was given because the mountain peaks from afar resemble stacks of wheat during the harvest season. The mountain is formed of purplish-red sandstone. Grottoes were cut into the side of the mountain to create Buddhist temples or grottoes, with murals, paintings, and sculptures of extraordinary beauty and transcendent expression.

Buddha sculpture in Cave 44, rumored to be based on Empress Yifu.

From pinterest.com

Empress Yifu (510–40) married Emperor Wen (507–51) in 525 CE, during the short-lived Western Wei dynasty (535–57). Three generations of Yifu’s family were married to royalty and became princesses or imperial consorts. Traditionally, Chinese patriarchs prefer male offspring. Daughters were thought to have little to offer to the family, especially after they were married off to their husbands’ clans. However, in Yifu’s case, it was considered better to have a daughter like her than to have sons. With her marriage and imperial status, Empress Yifu was a rare exception to Chinese social mores. She raised the status of women in her household and community by living an upright life. She did not lead an extravagantly luxurious life, and was a vegetarian. She was, by all accounts, kind-hearted and forgiving. She was never jealous of other women in the imperial harem, and eventually won the heart of Emperor Wen. However, this love did not protect her. Instead, it brought her tragedy.

Western Wei had been controlled by General Yuwen Tai since the disintegration of Northern Wei in 535. Emperor Wen had no real power. To form ties with the attacking Rouran Khaganate, Yuwen Tai forced Emperor Wen to dethrone Empress Yifu and to marry the princess of Rouran, Yujiulü. For the sake of her empire, Empress Yifu accepted her dethronement and became a nun on Maijishan to prevent war in 538. Despite the dethronement, Yifu continued to exercise influence on Buddhism and art. Her move to Maijishan brought along more developments in Buddhism, helping religious activities to flourish during her stay there.

Yifu raised the standards of Buddhist art at the time and pushed the quality of carving to a zenith in the Maijishan Grottoes. Her feminine features even impacted the sculpture itself in the Western Wei period, giving a female touch to the Buddha statues in Caves 20, 43, 44, 102, 120, 127, 147, and others.

Buddha sculpture in Cave 44. From pinterest.com

Maijishan survived several waves of war and Buddhist persecution, however the mountain could not withstand the forces of nature, and split into eastern and western cliffs during an earthquake in 734. Wooden walkways attached to the mountain like scaffolding are the only means of access to the cave temples along the cliff. The destruction of these walkways made access difficult or even impossible for some of the caves, which has protected the overall mountain from human interference.

The Maijishan Grottoes became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014. One of four famous grottoe sites in China, it has 194 caves in total, housing mainly painted clay sculptures and more than 7,000 stone carvings. As such, it has been dubbed the “biggest painted clay sculpture art museum in the East.” Due to the softness of the local sandstone, sculptures are mostly made from clay. It is quite a treasure to have so many clay sculptures preserved for more than 1,000 years.

The tragedy of Empress Yifu began when Emperor Wen secretly ordered her to keep her hair even as a nun, in the hope of arranging her return to the palace in the future. This inflamed the jealousy of Empress Yujiulü. Rouran launched an attack on Western Wei in 541. All officials pressured Emperor Wen to sentence Yifu to death to avoid all-out war. Emperor Wen reluctantly ordered Yifu to commit suicide. Yifu, like a bodhisattva, even wished Emperor Wen longevity and the empire stability, saying that she held no regrets over her sacrifice.

Empress Yifu was entombed In what is now cave No. 43. Cave No. 44, some 10 metres away, is believed to have been built by her son in her honor as the Buddha sculpture in Cave 44 bears feminine facial features.

Placard for Cave 43. Image courtesy of the author

Placard for Cave 43. Image courtesy of the authorThe art style of Western Wei, wanting to be accepted as the rightful heir of Northern Wei, did not deviate much from the late Northern Wei art style. The craftmanship was therefore mostly characterized by traditionalism, displaying less creativity. However, cave No. 44 saw an abrupt change in art style. The feminine face of the Buddha statue is more rounded than the usual slim, long face of the Northern Wei style, and resembles the face of a middle-aged woman such as Empress Yifu. As the sponsor of the cave was very likely Empress Yifu’s own son, the aura of his mother was incorporated into the crafting of the Buddha sculpture.

Buddhist art during the Western Wei improved rapidly from the very rigid Northern Wei art style to more realistic and humanistic depictions, fusing traditional sculpting principles with a new sense of creativity. The “Yifu style” smile is infectious: looking at the smile, one can immediately feel the calmness and tranquility that the mason intended to infuse into the stone and one cannot help but smile back.

When Emperor Wen died in 551, he requested to be buried together with Empress Yifu, so her remains were reburied in the capital of Chang’an. In Chinese history, female figures such as Empress Yifu were often characterized as the guilty parties or culprits behind wars. In the case of Yifu, it was only a weak excuse to cover up the weakness of Emperor Wen, who was controled by General Yuwen Tai, and also the commander’s failure to defeat the Rouran.

Under such circumstances, the Western Wei dynasty lasted only 22 years. The feminine smile of the Buddha also did not outlast the dynasty. However, Buddhist art during the Western Wei dynasty remains beautiful and unique, and continues to move us today.

See more

Inside the Lost Grottoes of Maijishan (Global Heritage Fund)

Buddhistdoor Global Special Project