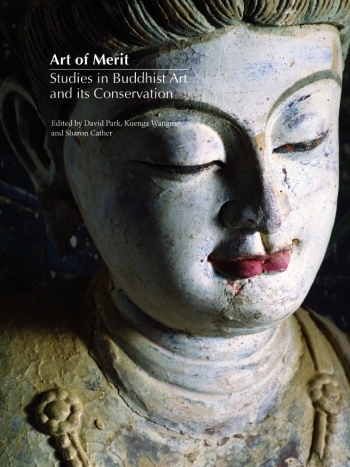

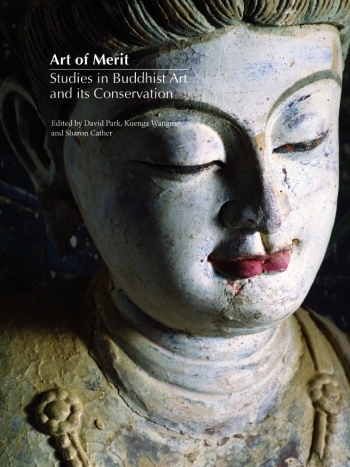

Front cover of "Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and its Conservation." From The Courtauld Institute of Art

Front cover of "Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and its Conservation." From The Courtauld Institute of ArtBuddhistdoor International would like to thank Professor David Park, Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art’s Conservation of Wall Painting Department, for kindly hosting us in London and providing a copy of Art of Merit to inform this book review, and Professor Deborah Swallow, Director of the Courtauld, for bringing Buddhist art as a systematic subject of study to the Institute for the very first time.

Even more inspiring than the sight of Buddhist art is the chance to admire it with a symposium of like-minded enthusiasts. The students and teachers at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art understand this better than most. Learning more about Buddhism’s artistic heritage was one of the objectives of its Buddhist Art Forum, which Buddhistdoor had the fortune to sit in from 11 – 14 April 2012. But another goal was to establish the subject of Buddhist art as a permanent part of the Courtauld’s curriculum. The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation not only hosted the 2012 Forum, but also founded a Center for Buddhist Art and Conservation at the Courtauld.

The Center then established an MA in “Buddhist Art: History and Conservation” in 2013, which is co-taught by specialists from King’s College London. Thanks to the guidance of Professor Deborah Swallow, the Courtauld prospectus now enjoys a special curriculum other British institutes do not yet offer.

At the Forum, contributors presented more than twenty-eight papers to an audience of students, academics, and the general public. The next task was to publish the conference proceedings, some of which were updated and revised. The very recent result is a beautiful volume called Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and its Conservation (Archetype Publications, 2013). Edited by David Park, Kuenga Wangmo, and Sharon Cather, this book covers four main themes about Buddhist art – definition, creation and function, conservation, and its role in the contemporary world. Yet it has done a remarkable job in uniting scholarly questions – important questions in their own right – with the pressing concerns of conservationists, devotees, and artists. Buddhist art is not an esoteric subject restricted to a small circle of academics. It attracts the reverence and worship of millions of practicing Buddhists, and possesses an ancient but living legacy of beauty. Buddhist art is a vital fragment of our common humanity, and Art of Merit is a scholarly tribute to this inheritance.

The papers in this volume offer, as Professor Park observes in his Introduction, “an extraordinary range of viewpoints” (p. xi). While Professor David Park concedes that Japan and Southeast Asia enjoyed relatively little attention, Art of Merit remains one of the most comprehensive volumes on not only Buddhist art but also the philosophy of Buddhist art. Questions raised by contributors range from the meta-artistic (“Is there a category of art called Buddhist art?”) to the specific (“Do the caves of Dunhuang serve a mortuary purpose?”) to the practical (“How should Buddhist art be preserved in the light of contrasting conservation philosophies?”). Given the diversity and interconnectedness of the subjects addressed, every monograph in the book deserves careful attention and reflection.

Nevertheless, some that focus on conservation evoke a greater sense of drama and urgency (no mean feat for an academic study). It is difficult to forget Professor Yoko Taniguchi’s presentation on Bamiyan’s conservation problems in 2012. The disquiet and alarm in the conference hall was real after she concluded her lecture two years ago, and to see her published research (pp. 124 – 152) in 2014 refreshes memories of the genuine passion and emotion that the entire audience felt for Buddhist art. “Conservators involved in this project cannot help but feel that wars and internal conflicts are profoundly impacting the work and overwhelming them… Politics… override the need for conserving this most important archaeological site. The only thing that can be done is to carry on with our aims” (p. 137). For this and so many other reasons, the vocation of Buddhist art remains a discipline that is inspirational and enjoyable, but as many conservators attest, troubling and frustrating too.

This book, as with others before it, offers pathways to understanding how Buddhist art has evolved and enriched human culture. It is also one of the most updated and diverse volumes available in Buddhist Studies. Despite standing on the shoulders of past giants, many problems and dilemmas remain. For example, what artifacts can be procured ethically for study in a museum or university? How should conservation projects move ahead where political and social concerns seem more pressing? How can we prioritize the most urgent sites and artifacts that stand a chance of being saved? Future generations of curators, conservators, and writers will have to take up these unfinished questions. But thanks to this book and the conference that inspired it, we have made a meritorious start.

More about this interconnected initiative

The Courtauld Institute of Art: The Courtauld Institute of Art is one of the world’s leading centers for the study of the history of art and conservation and is also home to one of the finest small art museums in the world. Based at Somerset House, The Courtauld is an independent college of the University of London. Visit the Courtauld’s website here.

Professor David Park is Director of the Courtauld’s Conservation of Wall Painting Department and Coordinator of the Robert H.N. Ho Family Center for Buddhist Art and Conservation. Throughout his career he has been involved in scholarly and conservation projects ranging from Romanesque art in England to mural paintings from Europe to Asia. His academic profile can be accessed here.

The Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation: Following Buddhism’s tradition of inspired donors, The Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation is a private philanthropic organization engaged in strategic, long-term projects in Hong Kong and around the world. Its mission is to foster and support Chinese arts and culture, as well as to promote deeper understanding of Buddhist philosophy. Since 2001, the Ho family has been building a global network of Buddhist learning through the endowment of Buddhist studies and academic centers at universities such as Harvard University, Stanford University, The University of Hong Kong, International Buddhist College in Thailand, The University of British Columbia, and The University of Toronto. The Ho family also initiated the establishment of Buddhistdoor, one of the largest and most visited global websites on Buddhism. The Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation and its activities, please visit its website.

Front cover of "Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and its Conservation." From The Courtauld Institute of Art

Front cover of "Art of Merit: Studies in Buddhist Art and its Conservation." From The Courtauld Institute of Art London's Courtauld Institute of Art. From The Courtauld

London's Courtauld Institute of Art. From The Courtauld