FEATURES|THEMES|Commentary

Meritorious Gifts at Tibetan Buddhist Centers in France: Some Paradoxes

Dhagpo Kagyu Ling in Landrevie, Saint-Léon sur Vézère. From dhagpo.org

Dhagpo Kagyu Ling in Landrevie, Saint-Léon sur Vézère. From dhagpo.orgBuddhism has become an established part of the Western religious landscape, although as recently as the 20th century it was difficult for many people to imagine how this non-monotheistic religion could take root durably in the West. Buddhism’s presence in the West is commonly categorized in two main forms (sometimes three: “import,” “export,” and “baggage” Buddhism*): so-called ethnic Buddhism, as represented and practiced by Asian immigrants, and Buddhism intended for Western consumption (such as Japanese Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, and Theravada), imported through the action of Asian masters and their Western converts. Tibetan Buddhism is predominant among the varieties of Buddhism available to Westerners in France, its success inseparable from the charismatic figure of the Dalai Lama, from the public’s perception of Tibet, which has been largely mythologized in the Western imagination, or from the Tibetan cause. The sympathy that Tibetan masters enjoy as a result, and their work in spreading the Dharma, has contributed to the success of the Vajrayana doctrine in France.

As of 2013, France was home 330 Dharma centers, among the highest in Europe. Dharma centers are either cultural or religious** associations; some are officially recognized by the Council of State as Religious Congregations (in 1988, Dhagpo Kagyu Ling, in Périgord, became the first non–catholic association to be granted the status of Religious Congregation.) Under the legislated separation of church and state (1905) in France, the government does not make financial resources directly available to religious associations (with certain exceptions), so Dharma centers must operate through the generosity of donors, membership resources, and by undertaking various paid activities. The majority of these centers are secular, intended for lay followers, while a minority are monasteries. There are also mixed centers comprising a small monastic community as well as lay followers. Some are open to the public, while others, such as retreat centers, are closed. Many rural Dharma centers are also community centers in which people live and work as volunteers. Here, the lifestyle is stratified by status—volunteer, resident, trainee practitioner, lay or monastic, Western or Tibetan lamas.

Like all religions present in France, Tibetan Buddhism has taken root and materially developed thanks in large part to the generosity of the faithful and the centers’ use of the Buddhist concept of meritorious gifts to encourage donations. Coming in various forms, these gifts are largely centered around the activities of one or more lamas. The living conditions of the first Tibetan masters to arrive in the West brought about a change in lifestyle for many of them, who have since left monastic conditions behind, and have adapted their teachings for a Western audience and introduced new practices.

The first centers date from the 1970s, and their number increased considerably from 1990 onwards, when the main parent centers began setting up satellite units in cities, which multiplied rapidly. Most are organized as follows: a parent center (often situated in a rural area with a hotel complex), humanitarian organizations, journals, a publishing house, a shop, and subsidiary centers (usually in urban areas). Restoration and extension projects for existing centers, the creation of new centers, and the building of temples, stupas, etc., are common and rely on donations and thus on the generosity of individuals. Since generosity is the first of the virtues or perfections (paramitas) taught in all Buddhist traditions, masters running centers systematically emphasize the benefits of gift-giving: acquiring merit, reaping good karma, dissolving the illusory self, finding the path to enlightenment, and so on. In Buddhist countries, particularly in the Theravada context, the offering of gifts in various forms (food, money, and other goods) is a fundamental practice based on the concept of merit, which structures relationships between the laity and monastics.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the central figure is the lama, who can be a layperson or a monk. Furthermore, in some Tibetan contexts, remuneration for ritual services is more frequent and widespread than gifts. In secular France, with a Christian tradition, some gifts or donations may be negatively connoted by converts (often of Catholic origin and rather critical of this religion) who are unfamiliar with the concept of merit. The meritorious gift, which is often perceived by converts as a calculation in the hope of a good rebirth, does not appeal to everyone (they are more sensitive to donations for humanitarian relief or patronage). The motivations and finality of gifts therefore differ from the traditional Buddhist context. Added to this is the way in which Buddhism is perceived by the majority in France—as a spiritual tradition of detachment. All this leads to contrasting interpretations of gift-giving practices, and to centers having to adapt their way of securing income by turning in particular to quasi-commercial activities; practices that are far removed from the Buddhist meritorious gift but which are often presented as such.

Appeals and calls for generosity add to the cost of the teachings provided, whether simple teachings or initiations, conferences, courses, or other collective or individual retreats. Prices vary; some session fees are particularly high (for example, €500 (US$533) for a week’s retreat), and various explanations for this are given: to make a profit, to compensate for losses incurred in previous years, or as a result of hefty rental and management costs. Weekly rituals do not usually have to be paid for, and some centers do not charge for meditation sessions or initiations, while others—in rarer cases—propose that attendees pay for sessions at their discretion for certain types of teachings. Free teachings are the exception, however.

The Tibetan issue has had a part to play in the success of Tibetan lamas: Dharma centers are not merely places for teaching and meditation, but sometimes also (decentralized) relay points for the exiled Tibetan government, even though the lineages are more or less independent. According to the official registration forms of the centers, the purpose of these centers includes the “promotion and preservation of Tibetan culture.” Thus, many Tibetan lamas who have settled in France have created cultural associations with a humanitarian vocation geared toward the needs of Tibetan communities associated with their lineage in exile or in Tibet.

In rural centers that offer annual programs of activities and often own hectares of land that needs to be maintained, staff must be hired throughout the year. In such centers, we can find several types of volunteer: permanent residents and other volunteers who hold a job, and have a social and a family life outside of the center. Those living in a center have to pay for food and lodging, even if they work for the community.

Behind what is presented as meritorious gifts, there is also a relatively wide range of practices that encourage followers to perfect their gift-giving. This includes traditional activities that guarantee the material conditions of life within a religious association, as well as ritual or religious services that are, in reality, of a lucrative commercial nature and which respond purely to economic motivations, although they are not presented as such. Denying the economic dimension of a Dharma center leads to the existence of a “double structural game” (Bourdieu, 113) in the discourse of those involved. The teachings do not have a price, yet a contribution or a session fee is formally requested.

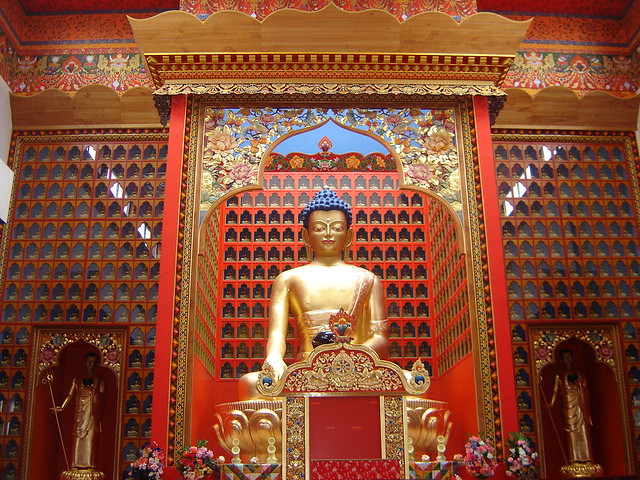

Buddha image in the Karmapa Temple at Karma Kagyu Monastery (Dhagpo Kundreul Ling, Auvergne)

Campergue. Image courtesy of the author

Finally, many Dharma centers, especially those that are part of large organizations, can be regarded as quasi-commercial enterprises that operate on the logic of the euphemized gift—a so-called meritorious gift that is not always understood and integrated by new converts. Tibetan lamas have adapted their discourse and their calls for generosity to forms outside the traditional Buddhist context. Practices relating to gifts and other transfers from Western converts to the master, to his organization and its affiliated charities, can indeed stem from traditional forms of patronage, however the primary interest of most converts to Tibetan Buddhism does not lie in practicing generosity, but rather in the tradition’s meditative and tantric practices, sustained by the charisma of the lama.

* “Import” Buddhism is when a potential convert actively seeks out the religion. “Export” Buddhism is actively disseminated through evangelistic activity, while "baggage" Buddhism is transmitted whenever individuals or families bring their beliefs with them when they migrate to a new country.

** France is a secular state that defines itself and its democracy as regulated by the principles of laïcité (with the concept of religious neutrality). However, the Council of State is in charge of determining which organizations are eligible for the status of an association for religious activities and which are not, during the handling of donations and legacies.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. “The Symbolic Economy of Goods” in Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford: University Press.

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Rediscovering Lamaism — The Western Relationship with Tibetan Buddhism

Who was Alexandra David-Neel? A Brief Story of a Buddhist Anarchist