FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

Monkeys, Catfish, and Demons in Priest’s Clothing: The Buddhist Roots and Themes of Japanese “Otsu-e” Folk Painting

Buddhistdoor Global | 2015-07-10 |

"The warrior Kumagai no Jiro on horseback," "Otsu-e" by Tosa Kenji (d. 1850). 18th century, ink and color on paper. From britishmuseum.org

"The warrior Kumagai no Jiro on horseback," "Otsu-e" by Tosa Kenji (d. 1850). 18th century, ink and color on paper. From britishmuseum.orgIn Japan during the Edo period (1600–1868), many people traveled on foot between the military capital, Edo (modern Tokyo), and the ancient imperial capital, Kyoto. The route connecting the two important cities was known as the Tokaido (literally the Eastern Sea Road); it was just over 300 miles long and took about two weeks to walk. Along the way were 53 government-sanctioned post stations for travelers to rest in, change horses, and buy food and souvenirs. The 53rd of these, and the last station travelers stopped at before reaching Kyoto, was the town of Otsu, located on the shores of Lake Biwa. This town was famous for acupuncture clinics offering relief for travelers’ aches and pains, abacuses (J. soroban), and inexpensive paintings, which have become known as Otsu-e, or “pictures from Otsu.” These roughly rendered paintings depicting many of the characters that could be spotted along the Tokaido were some of the most popular souvenirs collected by travelers passing through Otsu. Although most Otsu-e paintings are secular in nature, this 400-year-old folk art tradition had its roots in Buddhism and continuously featured Buddhist themes and motifs.

The Town of Otsu, by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). From The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido (J. Tokaido Gojusantsugi), Reisho Tokaido series, c. 1848–49, woodblock print on paper. From ootsue.com

The origins of Otsu-e are not entirely clear, but they were probably first made in the early 17th century in the Otsu area by artists specializing in cheap Buddhist paintings sold to the lower classes at the marketplaces adjoining major temples in the Kyoto area and to pilgrims visiting important temples such as Mii-dera and Ishiyama-dera in the Otsu area. These are the only known instance in Japan of religious paintings being executed by laymen without the patronage of the temples. Typically, the Otsu-e versions of more elaborate Buddhist silk devotional scroll paintings were painted on paper with hasty brushwork in a limited color palette and the faces of deities printed with woodblocks, making the paintings quick, easy, and cheap to produce. In addition, for the details that were rendered with gold leaf in temple paintings, the cheaper Otsu-e versions were decorated with a metallic powder made of brass filings.

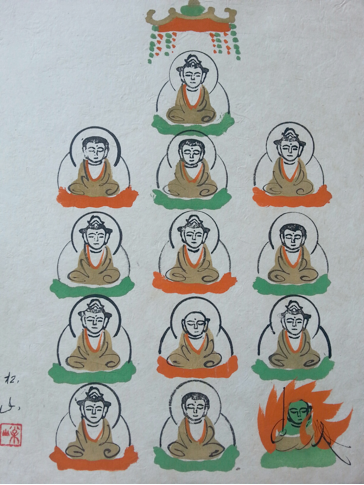

The Thirteen Buddhas (J. Jusanbutsu), Otsu-e by Takahashi Shozan (b. 1932). Late 20th century, ink and color on paper. Image courtesy of the author

The choice of images reflects the deities that were most popular among the general populace. There were apparently about 40 different Buddhist subjects depicted in the early Otsu-e repertoire. Most common were images of Amitabha (J. Amida), the Buddha of Infinite Life and Infinite Light, who promised his followers rebirth in his Western Paradise, and some early Otsu-e paintings of this deity show him descending from paradise flanked by two accompanying bodhisattvas to greet the soul of a deceased devotee. Also popular were images of The Thirteen Buddhas (J. Jusanbutsu), a grouping of 13 major deities that was important during rituals associated with death. Each of the deities was prayed to on prescribed days after the death of a family member. Although these early Buddhist paintings were probably not referred to as Otsu-e, it is interesting that the earliest recorded use of the term “Otsu-e” was in a haiku by Japan’s most famous poet, Matsuo Basho (1644–94):

Otsu-e no fude

No hajime wa

Nani botoke?

This poem translates literally as “The first brush of Otsu-e is which Buddha?” The verse may be suggesting that the first Otsu-e were Buddhist in nature, but more likely, Basho wrote the poem as a New Year’s poem, or kakizome, wondering which Buddhist image would be painted by a particular Otsu-e artist for his first painting of the New Year.

From the 18th century, Otsu artists continued to produce thousands of paintings to sell to travelers passing through their town, but rather than painting images of Buddhist deities to whom devotees prayed for salvation and assistance in the afterlife, they increasingly produced images that focused on the present life and many of its colorful characters. Over the next 200 years or so, about 120 subjects were represented, including secular figures like the lovely young woman called the Wisteria Maiden, who is dressed in a floral kimono and holds a branch of wisteria; a handsome young falconer; a blind man and a dog; and some rough, low-ranking samurai, who regularly accompanied their lords in their processions along the Tokaido. In addition, legendary figures like the heroic warrior Benkei and folk gods like the God of Wealth, Daikoku, and the God of Long Life, Fukurokuju, were also depicted, often in comical situations. In the 19th century, many of these characters were accompanied by phrases warning against evil, carelessness, and deceptive behavior.

Praying Demon (J. Oni no Nembutsu), Otsu-e by Takahashi Shozan (b. 1932). Late 20th century, ink and color on paper. Image courtesy of the author

Of all the characters portrayed in these folk paintings, the most beloved is the Oni no Nembutsu, the Praying Demon. In this image, a hairy demon figure with one crooked horn is dressed in the robes of an itinerant Buddhist priest with a gong around his neck, a striker in one hand, and a Buddhist subscription list (J. hogacho), a book containing the names of Buddhist donors, in the other. He is reciting the nembutsu, a chant believed by some Buddhists to help one attain salvation in a Buddhist paradise. The amusing image of a demon that has apparently converted to Buddhism is essentially a contradiction and has been interpreted in several ways. In fact, 19th-century images of this character are accompanied by various phrases, some warning against the superficial appearance of goodness, even within the Buddhist clergy, while others suggest that even the most evil beings can be saved by Buddhism.

Although this image of the demon dressed as a priest was the most popular among the Otsu-e repertoire, a similar demon is also depicted taking off his clothing and climbing into a wooden bathtub in a satirical image that mocks those people who attempt to cleanse their outer selves without first purifying their hearts. In another image, the God of Thunder, who is often depicted in formal paintings riding the clouds and beating his drum, is shown as an oni hanging out of a cloud and trying to retrieve his drum, which he has dropped into the sea. In this parody, the Otsu-e artists render a normally fearsome god harmless, suggesting that even gods are prone to misfortune. This image was later purchased as a protective charm against thunder and lightning.

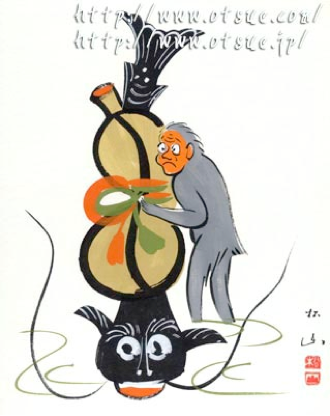

Monkey Trying to Catch a Catfish with a Gourd (J. Hyotan Namazu), Otsu-e by Takahashi Shozan (b. 1932). 1998, woodblock print on paper. From otsue.jp

Many Otsu-e images depict animals in comical situations, such as the cartoon-like image of a cat trying to catch a mouse by feeding it a chili pepper and then offering it sake to cool its mouth down. In another, a monkey is shown trying to capture a slippery catfish in a narrow-mouthed gourd. Though at first glance this appears to be a playful image of a monkey undertaking an impossible task, it is actually a visual representation of the well-known Zen koan, or riddle, “How do you catch a catfish with a gourd?” As in the case of most koan, there is no actual answer, but that is the point of such conundrums: the act of concentrating the mind on such puzzling questions is one method that can lead a Zen practitioner to enlightenment. However, the Otsu-e image of the monkey (and the phrases that often accompany this image) seems to be ridiculing the silly creature and warning against wasting too much energy on impossible tasks.

In the latter years of the Edo period, the tradition of Otsu-e was so influential among the populace that many major artists, including the famous Hokusai (c. 1760–1849), reproduced favorite subjects like the Praying Demon as expensive, elaborate paintings on silk. When the Tokaido route fell out of use by travelers at the end of the 19th century, the production and sale of Otsu-e declined, but there are still a handful of artists in Otsu today, including Takahashi Shozan (b. 1932), who are keeping the tradition alive. He continues to create images of Buddhas and Praying Demons with the bold brushstrokes and wry humor of earlier artists of a tradition that exemplifies the complexity of Japanese attitudes towards the Buddhist faith and its clergy over the centuries.

Meher McArthur is the author of a book on this subject, Gods and Goblins: Japanese Folk Paintings from Otsu (Pacific Asia Museum, 2000).

Categories:

Comments:

Share your thoughts: