I was born into a middle-class family in North London in 1955. I have mild dyslexia, so even though I got into grammar school I only did well in math and carpentry, and left just before my 15th birthday. I served as an apprentice mechanic for 18 months and then joined the Royal Navy, working in the engine room during war exercises on the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal. My parents divorced when I was 17, after which I lived on a series of canal boats, initially with my mother. I got married on my 21st birthday, had a son, and traveled the canals of England and Wales selling specialized rope work. The boat was pulled by my big horse, Jim. Three years later the marriage failed. I left with two new horses and a wooden Bow Top Gypsy caravan I had built myself. I then went to live and travel with the some of the last of the Gypsies, or Romany people, living in horse-drawn wagons in the UK. We traveled to horse fairs and beautiful rural locations, earning a living mainly by making wooden clothes pegs.

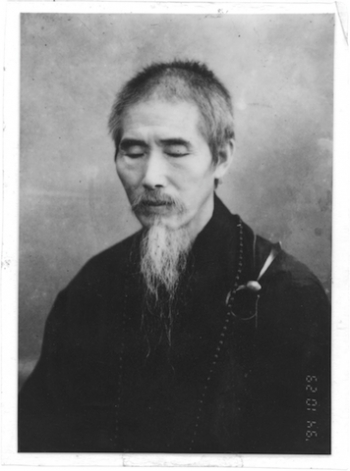

However, before that, something happened that completely changed my life—I came into contact with Buddhism, which was relatively unknown in England then, and I immediately recognized it as a true path to self-discovery and understanding. In 1972, at the age of 17, I came across a TV series about kung fu and a Buddhist monk, which I watched in fascination every week, absorbing the philosophy. I began to meditate almost every day on my boat, and later in my Gypsy caravan. I also became a strict vegetarian. Then, one day in Northampton, I stepped off my horse boat and went into a bookstore, where I found a book called The Secrets of Chinese Meditation, by Charles Luk (1964). On the front cover was a photo of Master Empty Cloud, or Xu Yun (c. 1840–1959). This immediately aroused such a powerful feeling within me that I bought the book and returned to my boat to learn about Chan (or Zen) meditation, Empty Cloud style. I then got hold of as many of Charles Luk’s books as I could find, learning as much as I could about Chan Buddhism and maintaining a regular meditation practice.

One day, I heard about a man living in the southwest of England called Bill Pickard, who was a teacher of the Empty Cloud style of Chan meditation. After writing to him I set off with my horse and wagon, working my way along the road by making and selling handicrafts. The journey took three months. When I got to Bill’s house he asked, “What are you looking for?” This is a huatou, or mind-before-thought question, and one I could not answer. It prompted me to ponder deeply. Bill then invited me—a scruffy, Gypsy-like figure smelling of wood smoke—to attend his meditation class. Soon afterward, I also took part in a serious Chan meditation retreat. The prolonged meditation on the huatou resulted in a depersonalized, clear, and bright mirror-like mind, where thoughts no longer disturbed me. I was so inspired that I sold my horse and wagon, enabling me to go to Hong Kong to search out some of Master Empty Cloud’s students.

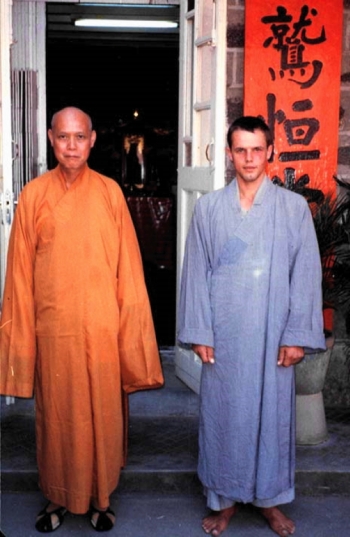

On 9 February 1984, with no knowledge of Chinese and no clear idea where I was going, I was on my first-ever flight. Once I arrived in Hong Kong, I took a taxi from the airport to the ferry pier and then a boat to Lantau Island, where there are a number of Buddhist monasteries. The next morning, I caught the bus up to the Chan monastery Po Lin, or “Precious Lotus,” and said that I wanted to be a monk. I was told I needed to see the abbot, Master Sheng Yi (Cantonese “Sing Yat”), or “The Saintly One” (1922–2010), who happened to be at another monastery nearby, at which he spent half his time. This was the smaller Chan monastery called Po Lam, or “Precious Wood,” a 40-minute walk from Po Lin along what is even today just a simple footpath. When I got there and met him, the abbot looked at me with great gentleness and seemed to have been expecting me. Amazingly, I discovered he was one of Master Empty Cloud’s students. The master suggested I go back to Po Lin to wait while he discussed the situation with all the monks, who agreed to let me stay.

To begin with, my accommodation was at Po Lin. Monastic robes were provided for me, and I sat in the meditation hall and hiked in the hills for about two months. The chanting seemed to come easily to me and was truly enjoyable. Later on, I would even lead the chant at meal times. Everyone was so kind, and I found Cantonese easy to learn and a lot of fun.

After some months, once Master Sheng Yi felt the time was right, I moved to the more secluded Po Lam Monastery, where there were no tourists. At the time only one eccentric monk was there, along with about 30 nuns. They fed me, and I helped them to cut scrub wood to cook with and carried food from the shop two miles away, using a bamboo pole on one shoulder. There were only cold showers and a hard, plank bed. We got up at 3.30 a.m. every day to chant mantras, which I loved. I also loved spending long hours alone in the Chan meditation hall.

The following year, the master shaved my head and gave me the name Hin Lic, meaning “Expanding Power.” I later received the Higher Ordination at Po Lin Monastery. I ate little, slept little, and practiced hard; there were also some long meditation retreats. At the end of 1985, Sheng Yi took me to China for about a month. We stayed at Cloud Gate and True Suchness monasteries, in Guangdong and Jiangxi provinces, respectively. Both these monasteries had previously been restored by Master Empty Cloud. I spent time with the older monks, some of whom would hold my hand.

Once we got back to Hong Kong, we held a number of inspiring but very intensive retreats at the Empty Cloud Memorial Hall in the New Territories. Sheng Yi then sent me to one of the world’s foremost Chan training monasteries, Songgwangsa (Spreading Pine Temple), in South Jeolla Province, South Korea. After some months, I moved to Japan to continue my studies at the Todai-ji Buddhist complex near Nara, Japan, before returning to Hong Kong. I finally left Hong Kong about three and a half years after I had first arrived.

The huatou technique in Chan forces you to search for who or what you really are behind the mind’s constant chatter. By simply asking “Who or what am I?” or “What is this conscious thing?” you can directly search out and realize your own True Nature, or the real Buddha within us all. With continuous practice, the usual egotistic self dissolves so that we can discover a purer state that is unlike anything we are familiar with in the material world. Instead, there is an absence of self, greed, hatred, and delusion, a freedom and a liberation that cannot be expressed in words. It is not unusual for serious practitioners to pass through this first barrier to attain kensho, or the initial enlightenment, but maintaining this state is very difficult indeed. A lifetime of dedication and determination is needed in order to be truly free of ego-based reactivity.

Over the last few years, I have been lucky enough to return to China a few more times for training. I am particularly grateful to True Suchness Monastery for allowing me to attend a 47-day meditation retreat last year.

I now run a small meditation group and work on a website dedicated to the life and teachings of Master Empty Cloud. For more information, please visit my site, Empty Cloud.

This article is one of a series on how Buddhism has impacted the lives of practitioners. We welcome you to send us your story as well.