As an anthropologist and artist, the individualistic and community-focused elements of pilgrimage journeys, which seem to meander easily between the personal and the communal, fascinate me. I am drawn to the ways that pilgrims cement their ties to transitional pilgrimage landscapes – either through storytelling, the construction of small shrines and sculptures, and/or the collection of photographs and other sacred mementoes in the landscape. ?

In the fall of 2011, I had the opportunity to craft a research project and expedition to investigate the potential of material culture offerings left along the Mount Kailash pilgrimage route to bridge linguistic and cultural barriers. While this project began as an Oxford University research project to investigate the role that material culture offerings play in constructing a unique Kailash pilgrim community – it soon evolved into something more extensive. ?

In Tibet, pilgrimage is almost universal. Pilgrimage routes circle sacred monasteries, shrines, and even towns. Larger pilgrimage circuits weave from sacred monasteries to sacred lakes, on circuits stretching thousands of kilometers. Pilgrimage in Tibet is undertaken as an exercise in ritual purification; pilgrims walk to cleanse their Karma and acquire merit. Offerings are part of this process, as are stories and myths.

In January 2012, I confirmed the expedition team – Lara Yeo (Expedition Treasurer), Don Nelson (Expedition Photographer and Medical Officer), and Alexander Darby (Expedition Linguist and Sound Recordist) and together we raised money through private and public institutions, funds, trusts, and individuals to undertake a journey overland from Lhasa to Mount Kailash.

In late May 2012, the alarm went off, following a series of self-immolations outside of the Jokhang Temple, in Lhasa. We were told that a ban had been imposed on all foreign travelers, and that this ban might last all summer. At that point we had a choice – to postpone our expedition until the following summer, or to continue as before, plotting a potential alternative itinerary through the Manaslu Region of Nepal, in the event that we would be unable to cross into Tibet. In the end, we opted for the latter. And on June 18, only five days before our departure, the ban on foreign entry was partially lifted. At the same time that we learned of the partial ban, an unforeseen medical emergency led us to negotiate Alex's dismissal from the expedition team. The loss of Alex not only meant the loss of a close team member and colleague, but it also meant the redistribution of our in-field research tasks. In the end, after much logistical turbulence, Don, Lara, and I arrived in Tibet in late June, to find a region rife with political tension. ?

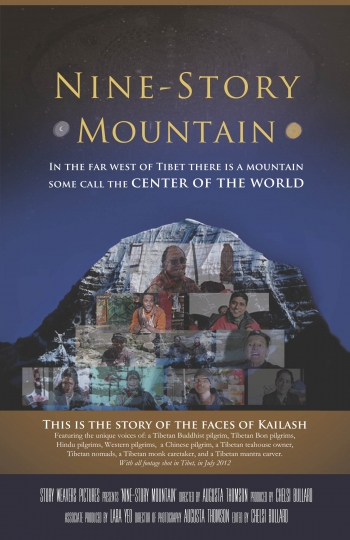

Over the course of four weeks in Tibet we learned a landscape unlike any other we had ever experienced. Our amazing guide and Tibetan crew introduced us to locals and took us to locations off the beaten path to aid in our research. When we were on Kailash, our guide and translator, helped to facilitate the interview process, such that we captured never-before-seen footage and anecdotes of Tibetan Buddhist pilgrims, Tibetan Bon practitioners, Hindu pilgrims, Western pilgrims, Chinese pilgrims, Tibetan teahouse owners, Tibetan guesthouse owners, Tibetan nomads, Tibetan monks and caretakers, and Tibetan mantra carvers. I spent most of the research period learning Tibet through a lens, and I will never forget how the colors of what we saw and experienced gave life to our film and story.

Nine-Story Mountain is our tribute to the landscape and culture, not only of Tibet, but also of a sacred mountain on the Tibetan Plateau, with the incredible ability to transcend territorial ties. Mount Kailash is one the few places in the world, claimed by oppositional religious faiths, where pilgrims of different ages, genders, and cultural backgrounds walk together in peace. It is one of the few transitional landscapes in the world, shared by people of different ages, genders, cultural, and faith backgrounds, where the culture is unequivocally one of tolerance and acceptance. Throughout the research project I kept looking for a hole in the fabric and culture of Kailash; I kept searching for the one broken strand. In the end, I found that the only broken strand was my resistance to believe.

This film is about the power of community. It is a testament to the strength of stories to connect people of different cultures and backgrounds. It is a testament to the power of hope and perseverance, to the beauty that exists, always, at the foundation. Even as the landscape changes and evolves to welcome tour operating companies and hordes of pilgrims I have faith that the beauty of Kailash will inspire a renewal. ?

This film is about the power of community. It is a testament to the strength of stories to connect people of different cultures and backgrounds. It is a testament to the power of hope and perseverance, to the beauty that exists, always, at the foundation. Even as the landscape changes and evolves to welcome tour operating companies and hordes of pilgrims I have faith that the beauty of Kailash will inspire a renewal. ?

I never thought that I would be the one to film Kailash, to try to capture its transcendence with a tiny HD camera. In the end, Kailash captured me.

Augusta Thomson is the director of Nine-Story Mountain and a student of Archaeology and Anthropology at Oxford University.

Back to Features

Augusta Thomson is the director of Nine-Story Mountain and a student of Archaeology and Anthropology at Oxford University.

Discover more about Nine-Story Mountain

Back to Features