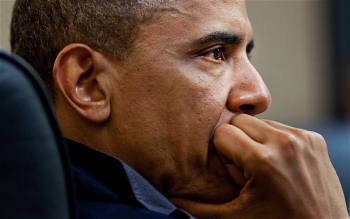

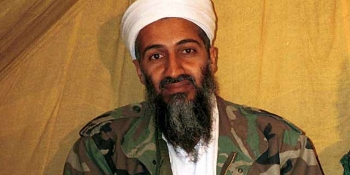

Last week, the leader of the free world, Barack Obama, watched on live camera stream one of the most successful and important operations ever conducted by his elite Special Forces, the American Navy Seals. The president of the United States and his staff observed as his symbolic nemesis and the archetypal terrorist commander, Osama bin Laden, was shot in the head and finished off with another bullet to the chest.

Personally, I don’t presume to know what the political, social and military consequences will be. But that hasn’t stopped journalists, pundits, analysts, advisors and scholars to speculate: a quick skim over the BBC or CNN websites is enough to tell a story of furious, flurried speculation, criticism, praise and worry in regards to this latest development. One thing that almost everyone in the Anglosphere seems to agree on is that Osama bin Laden being killed is a good thing, and that there is something excusable, condonable, or even morally wholesome about rejoicing in, celebrating, or at simply feeling happy, relieved, or satisfied by his death. Naturally, it is perhaps too much for a Buddhist (even if he may be American) to head down to Times Square or outside the White House, screaming at the top of his lungs about how elated and delighted he is at the death of a man, terrible as his crimes were. Indeed, the Mah?y?na tradition affirms that all beings, including bin Laden, will be eventually liberated from his own twisted delusions and suffering – but not without exhausting all his evil karma somewhere very unpleasant first.

There are two general attitudes that exemplify the attitude of the peaceful but justice-loving person. The first is American lawyer Clarence Darrow’s morbidly amusing observation: “I have never killed a man, but I have read many obituaries with a lot of pleasure.” The second, of course, is Martin Luther King’s (Jr.) insistence that one cannot decorate ugliness. One cannot valorize the meanness of spirit that inevitably comes with being happy at someone’s death, even if it is only a trace: “I mourn the loss of thousands of precious lives, but I will not rejoice in the death of one, not even an enemy. Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.”

Long before King, a Buddhist passage in the Dhammapada also echoed a similar sentiment that reflects the dark side of rejoicing at another’s death: “For hatred does not cease by hatred at any time: hatred ceases by love – this is an ancient rule.”

This does not mean that we cannot believe in justice. The disgustingly autocratic and revoltingly women-hating Taliban, who were intimate friends with bin Laden, lacked even the cultural indifference of past Muslim rulers, who were at least content to leave the Bamiyan Buddhas untouched, part of the Afghan landscape as much as the mountains they were carved in. But the Taliban, like many past Caliphate leaders who declared Buddhists idolaters in the name of controlling the economic routes of the Silk Road, was as greedy as it was militant. We of the Buddhist faith should not rejoice at death, but we have a right – and I would go so far as to call it a moral obligation – to align ourselves against the tenets of extremist Islam, the kind of political-theocratic Islam that has historically devastated our Buddhist territories and communities in Central Asia. It still continues to weave a narrative of hate against modernity and secularism today.

The incredible progress the United States made in just a few hours during the final confrontation with bin Laden is good for Buddhists as well. He was a symbol and embodiment of religious hatred, which has always been a weapon used against Buddhists along the Silk Road against Muslim conquerors who needed to write a narrative of legitimate conquest. With bin Laden’s death this deliberately simplistic narrative – the hypocritical jihad that al Qaeda and the Taliban (indeed, all extremist Muslims) use to legitimize themselves – has been proved to be inherently illegitimate, a mere extreme view that is ultimately incorrect for the mere fact that it is not moderate. It no longer is a narrative that can compete in the world of ideologies. It has lost a good degree of its force in the spiritual battlefield of religion. The free world may fear terrorist attacks, but they no longer fear the idea of terror, because it knows that it is a bankrupt ideal that has failed to deliver its promises. This is all the more true for the Arab Spring, where young Muslims are making changes and achieving incredible feats without the involvement of a single extremist group. Some twenty-eight year-old, unemployed, angry Egyptian has made a bigger difference in a matter of months as opposed to the terrorists’ hateful work of the past decade. Is it any wonder that al-Qaeda has no place in the modern world of legitimate religions?

Walking the Middle Way of morality is difficult. How can one not be happy at bin Laden’s death while asserting that it has made the world a better place? How can one believe in loving one’s enemy while sending Navy Seals against him? The questions are never easy, and the answers are never comfortable. Keeping in mind that passage from the Dhammapada and recognizing the very real complexity and grey areas of the world’s ethics, as tragic as death is, there was simply no other choice in the case of bin Laden. His killing was simply the result of too many mistakes made by too many people.