FEATURES|THEMES|People and Personalities

On Bells, Whistles, Hats, and Number Sets: An Interview with Jeff Watt on Buddhist Iconography and Himalayan Art

Jeff Watts at Sakya Nunnery. From jeffwatt.blogspot.hk

Jeff Watts at Sakya Nunnery. From jeffwatt.blogspot.hkJeff Watt is one of the world’s foremost scholars and curators of Tibetan and Himalayan art. He is the director and chief curator of Zhiguan Museum, Beijing, a visiting professor at Sichuan University, a guest lecturer at Oxford University, and executive director of the non-profit responsible for the Himalayan Art Resources website—perhaps the most comprehensive online database and resource for Himalayan art and iconography. From 1999–2007, Watt was also the founding curator of the Rubin Museum of Art in New York, which is home to one of the largest collections of Himalayan and Tibetan art in North America.

After dropping out of school at the age of 17 to undertake monastic vows from the 16th Gyalwa Karmapa, Watt studied extensively in India, Canada, and the US, with teachers such as Dudjom Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, and Sakya Jetsun Chimey. He disrobed in 1985, but continued to translate sacred Tibetan and Sanskrit texts, which led to a deep interest in Buddhist iconography.

Buddhistdoor Global recently had an opportunity to speak with Prof. Watt, and discuss his seminal work on Himalayan art and the Himalayan Art Resources website, which now hosts more than 100,000 images, over 5,000 subject pages, an organic outline (mind map) numbering over 1,000 pages, and images from in excess of 1,000 museums and private collections. This week the website celebrates its 20th anniversary, coinciding with Asia Week celebration of Asian art in New York City.

Shakyamuni Buddha flanked by the two principal students,

Shariputra and Maudgalyayana, and the Thirty-five Confession

Buddhas (Karma Kagyu). From himalayanart.org

Buddhistdoor Global: What first sparked your interest in Himalayan Buddhist art?

Jeff Watt: At the very beginning, I was actually more interested in Daoism but I found that, for me, Daoist beliefs didn’t go far enough in the areas I wanted them to. In addition, I felt Daoism had a strong element of Chinese culturalism—it was very Sino-centric—which made it less accessible to foreigners. So I moved on to Buddhism; to Guangdong Pure Land Buddhism to be precise.

I had a very nice teacher back in 1971/72, from Hong Kong. Although I was the only Western student among his 150–200 students, he would always translate the teachings into English as well. He was so very kind. It was on his recommendation that I went to study with a Tibetan teacher. I have always preferred the foundations of Buddhism over the bells and whistles, the hats and trumpets. And in Tibetan Buddhism there are a lot of hats and trumpets. So from the early 1970s, I spent a lot of time with what I describe as the Tibetan form of Indian Buddhism. There are some forms of Tibetan Buddhism which are indigenously Tibetan, but what I studied was more Indian Buddhism as studied in Tibet. Out of the major Tibetan lineages, the Sakya and Gelug Schools are more Indian and the Karma Kagyu and the Nyingma are more indigenous. They have been Tibetanised and are more revelation teachings.

Originally I wasn’t interested in art or art history at all. Himalayan art has three areas: art history, religious studies, and iconography. I had an interest in iconography, which is understanding the subject matter of the image or statue: the narrative figures, the symbols used, understanding the colors, and the meaning. In the early 1980s, I was doing a lot of translating work and a lot of these texts were about deities. I became very interested in the images that I came across, portable paintings and murals, etc., and their subject matter. I started asking people who was depicted in the painting, and what the painting was about. I became intrigued because most of the time, people couldn’t tell me; most of the time people didn’t know. If you show a Gelugpa lama a piece of Nyingma art, or vice versa, and ask them what is depicted, they will generally not know, or they’ll try to place it in their own context. I kind of made it a game of trying to figure out the figures depicted in a painting, and slowly realized that when you can recognize a painting or sculpture as Nyingma, you have to go to a Nyingma lama for more information. I was never interested in paintings and sculptures under the umbrella of art, I was interested in the meaning of the image, supported by my translation work.

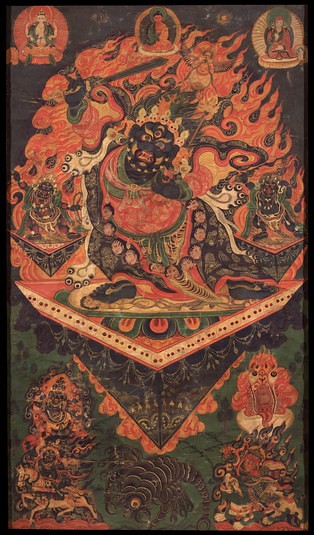

Black Hayagriva: from the Revealed Treasure

Tradition of Guru Chowang (1212–73) (Nyingma).

From himalayanart.org

BGD: Is this why you developed the Himalayan Art Resources website? To share the knowledge that was once limited to specific schools?

JW: I actually didn’t start the website. In the 1990s an art collector, Don Rubin, contacted me via a mutual friend. Don started the website in October 1997 and on his invitation, I joined in April 1998.

Originally I rejected the offer because they told me they didn’t want the website to be complicated or academic. It had to be faith-based and Dharma-centered. But my approach is different: if you want to build a website about Himalayan art, you have to include the Buddhist traditions, you have to relate the works of art to their source material and understand why it was created. You can’t just present a pretty picture and say “it’s about compassion,” or “the most important thing is faith in the guru.”

For instance, people don’t understand that there are six or seven reasons why Himalayan art is created:

1. Devotional;

2. Didactic: nobody bows to a wheel of life painting, the function of which is to show how awful samsara is. That is not sacred or devotional, that is didactic;

3. Representing a narrative: art can depict the previous life stories of the Buddha or the Buddha’s life story, or the life story of famous figures. We don’t get written biographies, until later;

4. Decorative: decorative Himalayan art was very popular, especially with the Chinese Emperors. They would ask artists to copy or paint images in a Himalayan style to decorate palaces;

5. Utilitarian: when art is meant to be used, usually statues;

6. Commodity: most of the art that you see commissioned by the Chinese emperors in the Himalayan style was meant for gift exchange, and gift exchange is a form of commodity exchange. For example, most of the Himalayan art you find in St. Petersburg, Russia, was part of a gift exchange between the Tibetan government and the Tsars of Russia. Tibetan lamas would write about artists painting pictures to sell to pilgrims and merchants, they would describe how this was not proper, and how bad the quality of the paintings were. So we have a very long trail in literature talking of the evils of the commodity of Himalayan paintings and sculptures.

I find that when people have too much of a Buddhist background, like some of my students, they have a hard time understanding the different reasons why art is created, which limits their understanding of the piece. They want it all to be sacred, they want it faith-based and Dharma-centered much like the website was originally was intended to be.

We ended up building the website like a database. Some people tell me the website is very complicated and that we should just restructure the whole thing, but that’s easier said than done. Our knowledge about Himalayan art is still expanding, as is the website, and it grows organically.

And at the beginning, we only focused on Tibetan art, which was also the original url: tibetart.com. But since then we have added art from the Swat Valley, from Kashmir, from the Himalayas, from Tibet, Northern China, Outer Mongolia, Southern Siberia, Kazakhstan. You have all of these art styles that can’t be called Tibetan art, so I changed the name of the website to Himalayan Art Resources in 2002.

A red-black, red, and white Tara from the same set of Twenty-one Taras of the lineage of Lord Atisha (No. 8, 13, 21 resp.; Gelug), part of the the collection of the Rubin Museum of Art. From himalayanart.org

A red-black, red, and white Tara from the same set of Twenty-one Taras of the lineage of Lord Atisha (No. 8, 13, 21 resp.; Gelug), part of the the collection of the Rubin Museum of Art. From himalayanart.orgBDG: You are now recognized as one of the leading scholars and curators of Tibetan and Himalayan art, but you were originally not interested in art and art history. How did this happen?

JW: Don Rubin ended up hiring me as the founding a curator for his museum, the Rubin Museum of Art in New York. I never wanted to do art history, but I found that every time I advised people to read the books of expert art historians, they would come back saying that they still didn’t understand. I thought that was ridiculous, but when I started reading these books, I found out that they didn’t make much sense. So I slowly started to get into painting and sculpture styles, and now I have developed a curriculum for Tibetan and Himalayan art.

I find that understanding Himalayan art is more difficult than understanding a foreign language, there are so many factors that you need to take into consideration. I recently summarized all these factors in my curriculum as: If you don’t know shapes and iconography, then you don’t know subjects. If you don’t know subjects, then you don’t know sets. If you know composition, then you don’t know styles. If you don’t know hats and protectors, then you don’t know religious tradition.

In the West and in China, people always argue about the style of a painting, but not about the composition. In Himalayan art, there are only four composition types, but two haven’t been practiced since the 14th or 15th century. Once we have figured out the composition styles, then we have to looks at institutions, regions, and then artists, and only through specific artists we can look at style.

In Himalayan art, all the different religious traditions define themselves with different colors and shapes of hats; the Karma Kagyu are black hats, Gelugpa is yellow, the Sakya is white, Nyingma is red. They also have very unique protector deities that are depicted at the bottom of many paintings, so if you recognize the hat and the protector deities, then you know the tradition to which a painting belongs. You might now know the details of the meaning of the art work, but when you know the tradition, you know where to get the information.

Then you have sets: half or more of the art featured on our website comes in sets. And the sets relate to something else. In Buddhism we’re big on numbers. We have sets like the three jewels, the Buddhas of the three times, the Buddhas of the eight directions, the Buddhas of the ten directions, then you have the eight medicine Buddhas, 45 confession Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas of this eon, the eight Taras that protect from the eight fears, you have the 21 Taras, but then you have five different systems of 21 different Taras. So you have these number sets that are foundational to Buddhism in general. To understand Himalayan art, you have to know your number sets. They are being reproduced in art.

And then there are the art number sets; the life story of the founder of the Gelugpa school, for instance, is always told in a set of 15 paintings. This number is artist convention, they are not Buddhist rules or based on any literature.

All of these aspects make Himalayan art very complicated. So when I develop a curriculum for Oxford University and/or Sichuan University, I try to explain all of these factors. I have written a lot of curriculums and I plan on publishing many of these on the Himalayan Art Resources website.

Jeff Watt giving a lecture in Hangzhou. From news.artron.net

Jeff Watt giving a lecture in Hangzhou. From news.artron.netBDG: It all sounds extremely interesting, what other future projects do you foresee?

JW: For the website, we hope to launch a Chinese version soon, I have been busy with this project for two years.

In addition, we need to establish a correct curriculum and some correct ways of looking at Himalayan art. Part of that is publishing books, text books. I have a contract with Sichuan University for a textbook. The website right now is the main resource for Himalayan art research, but websites are not accepted by a lot of American and North European academics. And often people feel it is okay to take our work and put their name on it, because they don’t respect us as a resource. So, we need to publish more. Some of my students have also asked for a teaching curriculum, a curriculum for teaching future teachers and professors of Himalayan art, so now that we have almost completed the curriculum for students, that is my next project.

See More

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

A Mission of Preservation: A Conversation with Prof. Luo Wenhua of the Palace Museum

From Chamonix to Chenrezig and Thangkas to Mountain Landscapes – The Story of Neljorma Tendron

Rare 15th–16th Century Murals and Sculptures Found in Sichuan Province Shed New Light on Tibetan Art

Pema Namdol Thaye: A Maker of Mandalas

Haunting the Himalayas: Spirits, Demons, and Gods in Tibetan Buddhism

Reflections on Learning to Paint like a Medieval ThangkaPainter: Hand-grinding Gems and Minerals into Pigment

From Manga to Monks, Anime to Arhats: Recent Buddhist Themes in the Art of Takashi Murakami