FEATURES|COLUMNS|Buddhist Art

One Hundred Shades of Grey: The Abstract Ink Paintings of Keiko Arai

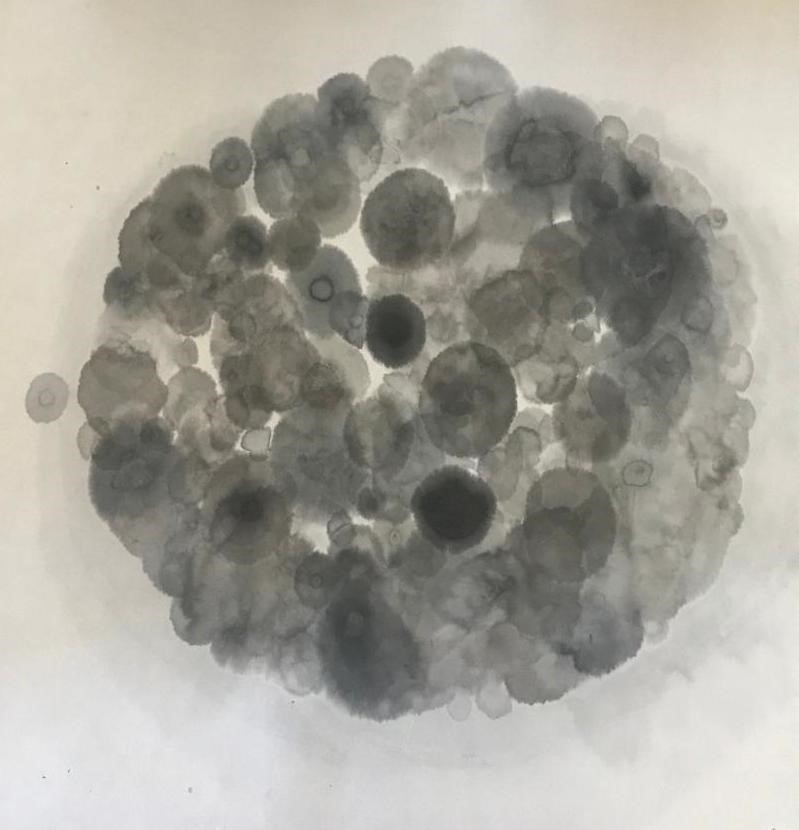

No.5 from the Hibikokugoku Series by Keiko Arai, Japan, 2015, sumi ink on

washi paper, 97x106 centimeters. Image courtesy of the artist

The ink circle has a distinguished place in the Buddhist ink painting traditions of Japan. For close to a millennium, Japanese Zen Buddhist artists have written calligraphy and painted simple but potent imagery in shades of black sumi ink on a white paper ground. One of their most iconic motifs has been the perfect circle drawn with one clean brushstroke, an artistic and spiritual gesture that is said to symbolize the entirety of the cosmos in a single stroke, and perhaps even enlightenment itself. Japanese artist Keiko Arai has taken ink painting and the concept of the circle in new directions, creating abstract ink paintings built up of circles formed with as many as 100 shades of traditional sumi ink. Her work at once explores the immensity of the external universe and the immeasurability of single cells and the unseen emotions that can inhabit a single being.

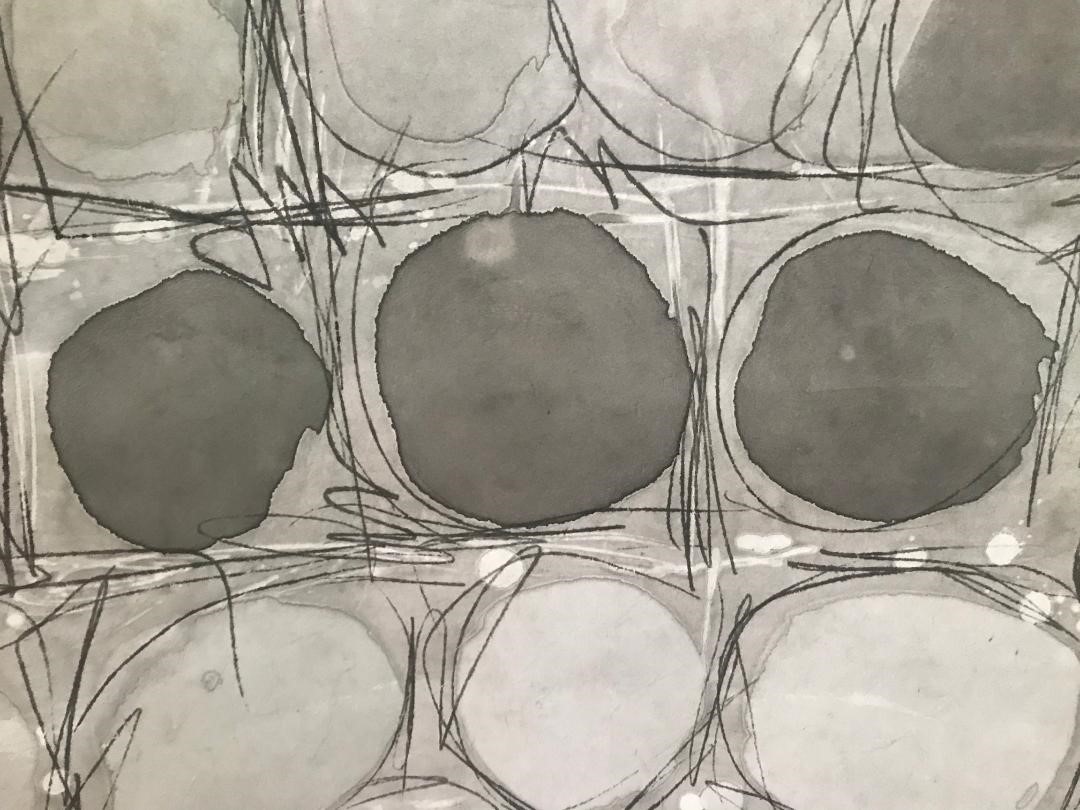

Detail of No.1 from the Hibikokugoku Series by Keiko Arai, Japan, 2015, sumi ink on

washi paper, 196x104 centimeters. Image courtesy of the artist

Arai, who is based in Chiba Prefecture near Tokyo, began her artistic training learning Western-style oil painting and studying Western languages and culture in college. From a young age, however, she had also studied the tea ceremony with the Urasenke school and became increasingly fascinated by the spiritual philosophy underpinning the world of tea, in particular, Zen Buddhist ideas of simplicity, spontaneity, and harmony with nature. Through her marriage, she gained an affinity with Zen Buddhism, as her husband’s family are adherents of Soto Zen Buddhism. Arai also found the confidence to take on any challenge, and the challenge she chose for herself was to learn Japanese traditional ink painting, known both as sumi-e, (ink picture) or suiboku-ga (meaning “water and ink painting”). Arai had long admired the monochrome ink paintings of natural landscapes and animal and human figures that graced the tokonoma alcoves of tea rooms during tea ceremonies, and in this highly spiritual East Asian art form—with its close connections to tea and Zen Buddhism—she saw potential for emotional and spiritual self-expression that she had not found in oil painting. She studied formally for a year and a half before leaving her teacher to paint alone and develop her own personal style.

Untitled from the Hibikokugoku Series by Keiko Arai, 2018. Sumi ink on washi paper. Image courtesy of the artist

Untitled from the Hibikokugoku Series by Keiko Arai, 2018. Sumi ink on washi paper. Image courtesy of the artistWhat Arai discovered through her exploration of traditional sumi ink and washi paper was the special relationship between the ink and the handmade paper. When applied to the surface of this thick paper, with its long, sturdy fibers, the ink not only seeps deep into the medium but also bleeds outward along the fibers, blurring edges and expanding her forms organically, as if the ink is breathing through the paper. Arai began what she calls “a dialogue with the materials, facing them with her thoughts, listening to their pulse and their breathing,” and what emerged was a body of abstract yet highly structured paintings infused with a meditative rhythm.

Arai also learned that there are so many shades of sumi ink that, when used together, they take on the appearance of different colors. In the suiboku-ga tradition there is an old Japanese saying—sumi ni gosai ari—which translates literally as “sumi has five colors,” but means that even black sumi ink has many different variations and that various colors can emerge in the achromatic world of ink painting through the skill of the artist and the wisdom of the viewer. Several years ago, Arai acquired a set of 100 different shades of ink—including some with tinges of blue, purple, and brown—and embarked on a series of works entitled Hibikokugoku, (Day after Day, Hour after Hour), a meditative journey in which she applies these subtly different “colors” to paper, one breath at a time. Of her relationship with each application of ink to paper, she explains: “I blow life into each of them and entrust them with my thoughts.”

What she discovered through her exploration of sumi ink and traditional washi paper was the special relationship that the ink has with the handmade paper. When applied to the surface of this thick paper with its long, sturdy fibers, the ink not only seeps deep into the paper itself but it also bleeds outwards along the fibers, blurring edges and expanding her forms organically, as if the ink is breathing through the paper. She began what she calls “a dialogue with the materials, facing them with her thoughts, listening to their pulse and their breathing,” and what emerged was body of abstract, yet highly structured paintings that are infused with a meditative rhythm.

Arai also learned that there are so many shades of sumi ink that, when used together, they take on the appearance of different colors. In the suiboku-ga tradition, there is an old Japanese saying – sumi ni gosai ari – which translates literally as “sumi has five colors,” but means that even black "sumi" ink has many different variations of color, and various colors can be seen to emerge in the achromatic world of ink painting through the skill of the artist and the wisdom of the viewer. Several years ago, she acquired a set of one hundred different shades of ink – including some with tinges of blue, purple and brown – and embarked on a series of works entitled Hibikokugoku, “Day after Day, Hour after Hour,” a meditative journey in which she applies these subtly different “colors” to paper one breath at a time. Of her relationship with every application of ink to paper, she explains, “I blow life into each of them and entrust them with my thoughts.”

Keiko Arai painting in her studio in Chiba, Japan. Photo by Yuki. Image courtesy of the artist

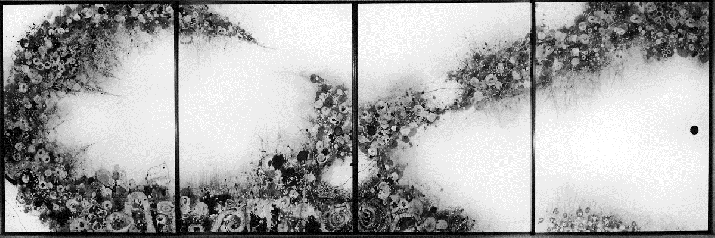

Keiko Arai painting in her studio in Chiba, Japan. Photo by Yuki. Image courtesy of the artistThe deeply spiritual quality of Arai’s ink painting has caught the attention of several shrines and temples in Japan. In 2013, she was commissioned to paint the fusuma, or inner sliding doors, of one of the reception rooms in Hojo-ji, a 450-year-old Soto Zen temple in Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture. Traditionally, the interior sliding doors of Japan’s Buddhist temples have been decorated with figurative imagery, such as mountain landscapes, symbolic bird-and-flower pairings, or real and imaginary animals such as tigers and dragons. For her paintings, which she entitled Ku et Chu (Sky and Universe), Arai chose to depict an abstract spiritual world—one in which life and death are interconnected and indivisible, and past, present, and future are unified. Representing death with more severe, darker ink tones and life with lighter tones, she built a dense, fluid, and swirling universe with layers of ink circles, each flowing into the paper and into each other like a mass of souls, breaths, or emotions, while also giving way to the silence and stillness of the surrounding white space.

Detail of Ku, one four-panel section of the Ku et Chu fusuma door painting from Hojo-ji, a temple in Funabashi, Japan. 187x96 centimeters, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist

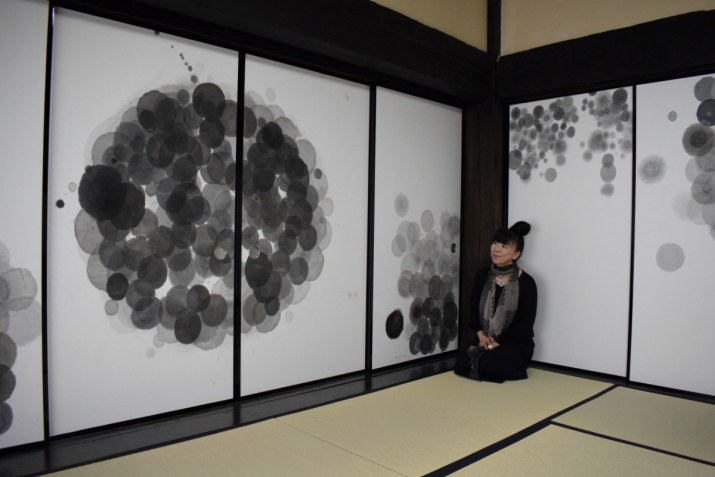

Detail of Ku, one four-panel section of the Ku et Chu fusuma door painting from Hojo-ji, a temple in Funabashi, Japan. 187x96 centimeters, 2013. Image courtesy of the artistIn 2017, Arai was commissioned to paint the fusuma in the main rooms of one of the shrine buildings of the Okamoto Otaki Shrine in Echizen, the heart of Japan’s papermaking tradition. Located in Fukui Province, on the northwestern coast of Japan’s largest island, Honshu, the Shinto shrine is dedicated to the goddess, or kami, of papermaking, and this commission was part of the celebrations of the 1,300th anniversary of the shrine’s establishment. For this large-scale painting that extended over a total of 32 door panels, she brought together ink, water, and paper to create a playfully meditative interior space. Here, the soft roundness of her ink formations balanced perfectly with the abundant white space of the screen doors and the bold lines of the traditional Japanese room. The result is an innovative and elegant offering from a contemporary suiboku-ga artist to the ancient goddess of one of the nation’s most treasured artistic materials.

Keiko Arai in front of the fusuma door painting at the Okamoto Otaki Shrine in Echizen, Japan, 2017. Image courtesy of the artist

Keiko Arai in front of the fusuma door painting at the Okamoto Otaki Shrine in Echizen, Japan, 2017. Image courtesy of the artistSee more

Exhibition “The world of ARAI Keiko”. Drawings dedicated to the shrine are also exhibited (Geisen)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

The Monks and Mandalas of Ato Sengai

Challenging Reality: The Painted Sculptures of Masayuki Tsubota

Meaning in the Face of Transience: Reflections of Socially Engaged Buddhists in Japan

Senso-ji: A Buddhist Temple for the People

Beauty and Sadness: Reflections on a Japanese Noh Play