Beginning in the mid-1980’s, American scholars John and Susan Huntington turned Buddhist art history on its head with claims that the first Buddha images were made shortly after the Buddha’s death, and that art known as aniconic – art without an anthropomorphic Buddha – was not aniconic at all. While their ideas were largely dismissed, their claims rekindled interest in a subject that had lain dormant for six decades.

In a fortuitous moment of synchronicity, the appearance of Susan Huntington’s 1990 paper, Early Buddhist Art and the Theory of Aniconism, coincided with a period of active research on early Buddhist art by Colombia University professor, Vidya Dehejia. In a series of articles in the early 90’s, Dehejia and Huntington engaged in an exchange of ideas that continues to be cited widely.

Arguing for a more nuanced reading of early stupa reliefs, Dehejia (1991) claimed the symbols of the Bodhi tree, the wheel, and the stupa not only have multiple meanings, but can and have been read in different, often overlapping ways.

First, they can be read as deliberately aniconic. That is, the symbols were intended to stand in place of an anthropomorphized Buddha. They can also be read as symbols representing sacred places – Bodhgaya, Sarnath, and Kusinara. Lastly, they can be read as “attributes of the faith” – the tree as wisdom, or the wheel as the scared law.

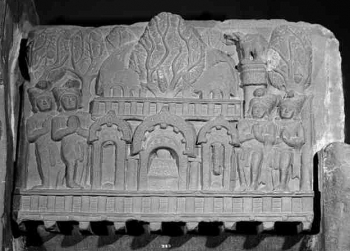

How the symbol is read depends on its context, but even when one aspect is primary, secondary meanings may be associated. Dehejia offers the example of a narrative scene at Bharhut depicting the enlightenment (Figure 14). The artist included

a shrine around the Bodhi tree that was not built until two centuries after the historical moment of the enlightenment. While the prime intention of this panel was to depict the historical event, the artist’s portrayal of the shrine also suggests the holy site. (1991, p. 33).

A visitor to Bharhut, then, on viewing this panel might have seen the tree as part of the narrative, or as a symbol representing Bodhgaya, or if perceptive, perhaps both. Visual art, Dehejia argued, is as layered as literature.

In 1997 Dehejia delivered a book length treatment on the development of narrative modes of early Buddhist sculpture and painting. Her primary interest was in creating a classification system for these modes as found at the early monuments. By modes she referred to how artists used space to tell a story. Altogether she identified seven modes.

Some artists, for example, might depict a single scene from the life of the Buddha within a single panel. Another artist might try creating a sequence of two or three scenes in a similar-sized space, repeating the figure of the protagonist in each mini-scene. Other artists created similar sequences but with a difference. Instead of repeating the central protagonist, they made only one, but they made him oversized. This signaled to the reader that this character belonged to each mini-scene.

As she worked to produce this scheme, Dehejia began to notice a historical process unfolding. Artists at Bharhut depended on simpler forms than those at later sites like Sanchi and Amaravati. Still, this was not an evolutionary process in which old forms were replaced by new. Extending her metaphor, she noted that old modes persisted even when new ones arrived, just like in literature, in which “the modes of drama, poem, and satire continued to be popular down the centuries though there may have been periods or centers where one or the other was marginalized.” (1997, p. 271)

A Swedish researcher publishing at about the same time had his own historical concern. He noticed that the work of this period, spanning at least 400 years (from 200 BCE to 200 CE), was treated as a type without sensitivity to how symbols and signs may have evolved. When he looked at the art as it developed historically, Klemens Karlsson (2000) confirmed Coomaraswamy’s observation seventy years previous, that early Buddhist art was not really Buddhist at all, but simply part of a nonsectarian Indian tradition.

Karlsson points, for example, to soapstone seals found at Pakistani archeological sites of Mohenjo-dara and Harrapan, dating from 2600 BCE, two millennia before the Buddha. (Figure -15). Approximately 2-4 cm square, the seals are thought to have been used to keep records, or worn as amulets, and feature depictions of mostly animals. Other depictions are symbols - in slightly different form - known to Buddhists: people worshipping in front of trees, animal horns shaped as tridents, and six-spoked wheels. Punch-marked coins from the pre-Buddhist era also feature trees within railings, wheels, tridents, and stupas.

By the time the Buddhists arrived, other religions were already on the scene. One of Buddhism’s closest philosophical cousins and rivals was the Jains. Karlsson points to evidence from Mathura, home to large Jain and Buddhist communities that shared not only a common geographical space, but a common visual vocabulary. Like the Buddhists, the Jains also built stupas, complete with railings and gates, which they decorated with symbols similar to those used by Buddhists. Karlsson notes about one image in particular (Figure 16). that “without identifying inscriptions it would have been impossible to decide” if it were Jain or Buddhist. (2000, p. 148).

Karlsson’s most welcome contribution to the discussion has been something long overlooked, what he called his Preliminary Chronology of Buddhist Aniconic Art. Dehejia had been similarly interested in historical development, and the ordering of her chapters, each focusing on a specific site, suggested a chronology. Karlsson was more explicit. And where Dehejia focused primarily on narrative modes, Karlsson focused on the symbols used within those modes. He divided his Chronology into four periods:

Period 1: Non-Buddhist

Until mid-2nd century BCE

The initial period is characterized by the use of signs and symbols common to all Indian sacred sites. These include lotus flowers, animals, mythological creatures, wheels, tree railings, stupas, lion pillars and tridents. Except for one relief, there is no sign of humans venerating sacred signs.

Period 2: Early Buddhist Aniconism

Mid-2nd century BCE to 1st century BCE

The second period is transitional, featuring a continuation of the symbols found in Period 1, with the appearance of distinctly Buddhist symbols. These include altars in front of trees, wheels, pillars and tridents, as well as the first footprints. One of the altars appears to be in the shape of an empty throne, and several scenes depict people worshiping at some of these objects. The first narrative art appears.

Period 3: Developed Buddhist Aniconism

Mid-1st century BCE to 1st cent CE

The mature period of “developed Buddhist aniconic art” uses many of the most common symbols (a tree, a wheel) to refer specifically to the Buddha in a narrative context.

Period 4: Formulaic Buddhist Aniconism

2nd century CE

This period sees aniconic art losing its narrative function, the symbols being “repeated over and over again” in a “highly formalistic” fashion. The first anthropomorphic Buddha images are produced and appear alongside the aniconic symbols.

In order to get from Period 1 to Period 2 and prove his thesis, Karlsson provides examples of how the use of symbols changed over the course of 300 years. As has been noted, pre-Buddhist seals and coins featured sacred trees, even trees enclosed by railings (suggesting ritual religious behavior). Pre-Buddhist Indian religious texts, the Vedas, refer to scared trees, which the Jains likewise depicted in their art. Like the Buddhists, the Jains adopted this symbol from the culture in which they flourished. Karlsson believes the tree was initially used as decorative art at Buddhist holy sites simply to mark a space as sacred. Progressively, the tree began to be associated with Buddhism and a buddha, and the evolution of the symbol was completed when the tree became a sign pointing to the Buddha and his enlightenment.

The same process is evident in the symbol of the wheel, an ancient sign connected with sovereignty. Prehistoric seals from the Indus Valley civilizations feature six-spoked wheels. The wheel was used from Vedic times to symbolize the sun and the sun-god Surya. And as with the tree, the Jains also used wheels. Karlsson notes that the wheel became distinctly Buddhist when it began to be depicted with eight spokes, associating the symbol with the Buddhist tradition of an eight-limbed path of personal transformation. At the Sanchi stupa, there are wheels of 16, 20 and 25 spokes, suggesting these wheels were not yet specifically Buddhist wheels. Karlsson believes scholars have taken examples from later periods of art, where the wheel was clearly a symbol of the Buddha’s teaching, and read back into history, assuming (as with the tree) that every earlier example was a clear case of aniconic symbolism.

Karlsson concludes with a provocative point:

It is also important to recognize that signs used by the Buddhists were not adopted only to illustrate already existing Buddhist dogmas or stories. Some of the signs may have influenced Buddhist writings as well. The development of Buddhist art and literature was a gradual and mutual process. There was an interaction between events told about the Buddha and visual signs from ancient Indian art. Here as in all places, art creates stories and stories create art. (2000, p. 173).

The wheel, for example, may have influenced the story of the First Sermon. Karlsson notes that canonical sources for the First Sermon vary, and that the wheel metaphor is strongest in later layers of the canon. He notes also the earliest Chinese translations do not include the First Sermon, and that what is left of the inscription on the pillar erected by Emperor Asoka 200 years after the Buddha’s death (in the park where the Buddha is thought to have given this initial teaching) does not contain any reference to the First Sermon. The nativity image is even more clearly evidence of ancient symbols influencing the telling of Buddhist stories. Tree goddesses were typically depicted standing next to trees, one hand grasping a branch (Figure 17). , which is exactly how the Buddha’s mother, Queen Maya, is depicted birthing her son (Karlsson, 2006).

Karlsson’s implied question is, “How should we read this art?” This gets right to the heart of the puzzle of aniconism as it has been argued for the past century. Should the absence of an anthropomorphic Buddha be seen as visual expression somehow lacking, as not yet fully developed? Or might it suggest something more?

References

Dehejia, V. 1991 Aniconicm and the Multivalence of Emblems. Ars Orientalis. 21 (1) 45-66.

Dehejia, V. 1997. Discourse in early Buddhist art: visual narratives of India. New Delhi, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Huntington, S. 1990 Early Buddhist Art and the Theory of Aniconism. Art Journal. 39 (4) 401-408.

Karlsson, K. 2000. Face to face with the absent Buddha: the formation of Buddhist aniconic art. Uppsala, Sweden, Uppsala University.

Karlsson, K. 2006 The Formation of Early Buddhist Visual Culture. Material Religion. 2 (1) 68-95.

Back in My Image series homepage