The concept of a modern or contemporary Tibetan art is a relatively fresh phenomenon arising out of the second half of the 20th century. The work of artists like Tenzing Rigdol and Gonkar Gyatso recently took center stage at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s special exhibition Tibet and India: Buddhist Traditions and Transformations. The show brought together objects from two transformational moments in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, where radically new vocabularies and expressions emerged and developed out of complex cross-cultural interactions. Devotional objects from the 11th and 12th centuries demonstrated how the esoteric imagery of northern India shaped and continues to underscore the distinct aesthetic of Tibetan art. Alongside these, the contemporary works of Rigdol and Gyatso showed how Tibetan artists of postmodernity are incorporating radical new forms and concepts into the canon of Tibetan art.

Since the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet, the region’s art has almost exclusively been associated with religious practices. This corpus of traditional religious imagery has become synonymous with our idea of what Tibetan art is and by extension, our perceptions of Tibet and “Tibetan-ness.” The works of contemporary artists such as Rigdol and Gyatso are challenging these assumptions and have brought a new voice to a younger generation of Tibetans. However, even as the widely divergent expressions of these artists have gained greater exposure within the secular world of contemporary art, the visual languages and concepts of Buddhism continue to shape their aesthetics. Though these pieces do not strictly read as “Buddhist” art, the inclusion of Buddhist themes and motifs roots them to this tradition. Intentionally or not, the Buddhist influence continues in this new generation.

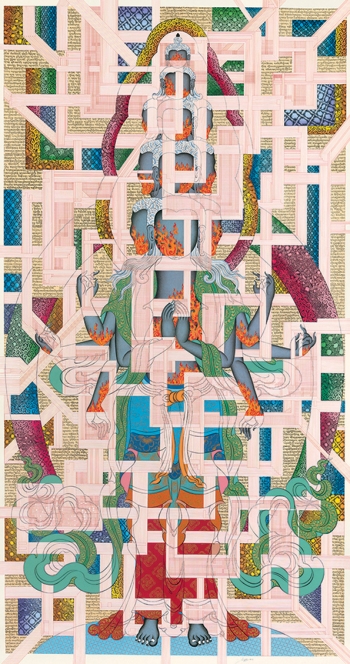

An example is one of Rigdol’s works, Pin drop silence: Eleven-headed Avalokitesvara, especially commissioned for the exhibit. Interlocking sections feature the underdrawings of Tibetan thangka paintings as well as pages of Tibetan text. The fragments interweave into a central, multi-headed figure of Avalokiteshvara, obscuring the deity but also revealing the layers of workmanship involved in traditional painting.

This aesthetic perhaps alludes to, but perhaps also erodes or washes away, tradition. It is believed that an image does not become an embodiment until the eyes of the deity are revealed and significantly, Rigdol depicts Avalokiteshvara as a faceless deity, clearly distinguishing the piece from a sacred object of worship with which we can connect. Details of the divine form instead are replaced by a striking motif of rising flames, which can be further read as symbolic of the erosion of Tibetan culture and identity or the absence of spirituality in contemporary life.

Still, the message remains oblique and open-ended. The piece could just as easily be read as an expression of emptiness or the intangible yet indestructible presence of the deity. By revealing the proportional, technical grid system involved in creating thangka paintings, we become aware of the human hand that has for so long been regarded by historians as “invisible” and indistinguishable in traditional Tibetan painting. In this sense we are prompted to consider the possibilities of an alternative visual history of Tibet, which also includes more individualistic, expressionistic forms of the creator. The result is intimate and immediate, and we feel a greater connection to the work of art when we understand the labor from which it was born.

Rigdol’s medium and aesthetic present a potent and refreshingly unique perspective within the broader international contemporary art scene. This perhaps reflects a wider recognition among a young generation of Tibetans of the fact that intellectually ignoring the realities of an increasingly internationalized world might only result in a sentence to perpetual marginality. At the same time, being over-attached to keeping up with modernity’s trends could jeopardize traditional cultural and spiritual identity. The possibility or impossibility of overcoming this continual tension is apparent in the search for an expression that has the capacity to be “Tibetan,” “modern,” and in many cases, it seems, “Buddhist.”