FEATURES|COLUMNS|Chasing Light

Poison Is Medicine: Paradox and Perception in Vajrayana Buddhism

From khyentsefoundation.org

From khyentsefoundation.orgHow should prospective students approach the Buddhist teachings—in particular those who aspire to take the precarious Vajrayana path and in particular those students approaching the path from a Western background? And how should tantric teachers receive such students and guide them using means that take into account temperament and cultural conditioning, that respond to aptitude and capacity, all the while maintaining a firm footing on the fundamental bedrock of the Buddhadharma that does not dilute or deviate from the fundamental teachings?

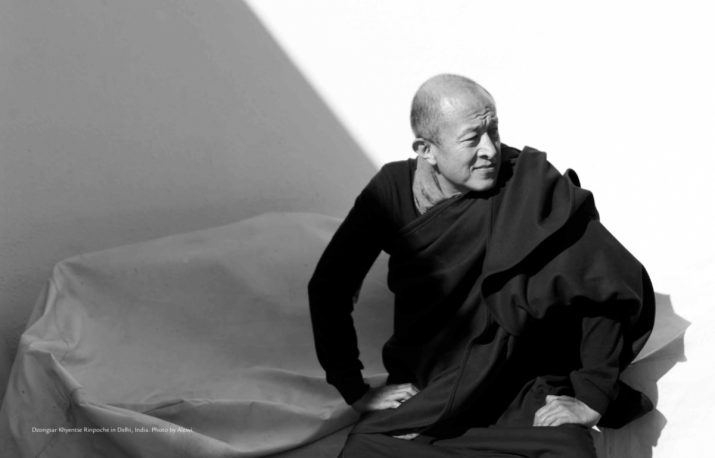

It’s these weighty questions and their profound significance that the renowned Bhutanese lama, filmmaker, and author Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche seeks to explore and address in his new book Poison is Medicine: Clarifying the Vajrayana. An insightful and pragmatic state-of-the-union address, the book’s message is borne in the turbulent wake of a series of high-profile scandals that have had far-reaching repercussions within the realm of Vajrayana tutelage and have rippled out into the wider world as we acknowledge the suffering of the victims of abuse and the grave implications for their abusers.

In this light, Poison is Medicine is an ambitious undertaking, arduous even. It seeks to explain, to justify, to “clarify” the Vajrayana as a methodology and spiritual view in a way that might speak to the sensibilities of a modern audience, while pointing out the inherent pitfalls, dangers, and vulnerabilities of the path, and recognizing the potential for misuse that has always existed within the tradition.

As Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche states in his introduction:

Poison is Medicine was written in response to the misunderstandings and misapprehensions about the Vajrayana that were exposed by the Vajrayana guru-related scandals of the 2010s . . .

One of my reasons for writing this book is that I would like us all to think about and examine the various issues the recent Vajrayana guru scandals have brought to light, from as many different angles as possible.

My wish is to offer aspiring Vajrayana students a few tips from the tantric texts about how to choose their guru. This book will, I hope, point you in the right direction by supplying you with the tools you need to examine a guru thoroughly before committing yourself. (vii)

From the outset, such an intention might seem to present an almost impossible mountain to scale; how does one, even a celebrated lama, frame the ineffability of the ineffable within a conventional, dualistic perspective? No amount of explanation or contextualization can absolve a charlatan or a hypocrite of gross misconduct in a relationship of the most profound and fragile trust, and yet this is an issue that must be broached, examined, and understood if further abuses are to be avoided and if tantric expressions of Buddhism are to be allowed to flourish in modern societies. In the contemporary context, Rinpoche concedes, some reassessment is required of both the tradition of following a guru and of the systems and conventions that educate future teachers.

As a highly trained, highly respected icon of the modern Vajrayana tradition who has, by comparison with many teachers from the Himalayan region, made great efforts to embrace and interpret the characteristics and idiosyncrasies of modern Western-influenced cultures, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche is eminently equipped for this task, if anyone may be. But this role is hardly an enviable one. Against a backdrop of livid divisions within the temporal and cultural world of the Vajrayana, the sanctity of the guru-disciple connection—of mutually upholding the samayas, and the giving and receiving of abhishekas—must be preserved and nourished. Key to respecting this relationship is the delicate, almost impossible balance of rising to the challenges, commitments, and obligations that face each and every aspiring student and guru, which Rinpoche pinpoints without resorting to victim-blaming nor absolving the corrupted of their transgressions:

These days, the chances of any of us meeting a realised mahasiddha, let alone becoming his or her student, are slim. However much you long to follow the tantric path, choosing a tantric teacher can be intimidating. It’s such a gamble! And although we are told again and again how important it is to analyse the guru and the path, we are rarely told what it is that needs analysing or how to analyse it. This book will, I hope, point you in the right direction by supplying you with the tools you need to examine a guru thoroughly before committing yourself. I should add that if, by some miracle, the guru you are interested in turns out to be a mahasiddha, not one word of this book is relevant or necessary. (viii)

From khyentsefoundation.org

While refraining from indulgence in gratuitous iconoclasm, Rinpoche nevertheless proffers frank reminders that this intimate act of surrender and faith must be accompanied, as emphasized repeatedly in traditional texts, by rigorous and, where necessary, lengthy examination, analysis, and reflection—a mutual vetting of teacher and student—before being undertaken.

Unfortunately, today’s gurus become jaded very quickly. They don’t notice how hard it is for contemporary students to ask a teacher to become a guru, or what people are prepared to put themselves through in order to do it. But shouldn’t the lamas be just as nervous as the students? After all, the relationship between a Vajrayana guru and student is not only far more complicated than that of a married couple, it is of far greater consequence. Strictly speaking, a Vajrayana guru who takes their bodhisattva vow seriously should consider each student to be their principal project, not just in terms of the enlightenment of that student, but as a step towards the enlightenment of countless other sentient beings. To me, it’s mind-boggling that lamas like myself don’t have sweaty palms, or tremble and fumble each time they accept a new student. I hope and pray that all future gurus will become just as anxious and jittery as their students. (xxi–xxii)

Rinpoche covers a lot of ground: from Stephen Batchelor to Kali to Guru Padmasambhava. From the importance of lineage to the paradoxes and contradictions of relative and ultimate truth. From the implications of refuge to the methods of “crazy wisdom” and skillful means. He draws on historical precedents and all-too-human hurdles and obstacles that have confounded student and teacher alike for centuries, yet also acknowledges how modern manifestations of this sacred bond have somehow gone awry: how fundamental aspects of the Vajrayana have been and continue to be lost in translation—to language, cultural conditioning, preconceptions, expectations—how teachers have fallen short of ideals and responsibilities, and how students have found themselves unprepared, out of their depth, and ill-equipped to deal with the consequences of their choices.

Clearly, the Vajrayana guru-student relationship should never be entered into lightly, but it often is. And when things go wrong, the root of the problem—the misunderstanding, error or mistake that was made—can usually be traced back to the moment the student stepped onto the Vajrayana path and first entered into a relationship with a guru. (xxiii)

Before student and teacher enter into a Vajrayana guru-student relationship, they must both be clear in their own minds about what they are doing and why. Initially the student’s motivation might be the wish to attain enlightenment, but motivation is fragile, easy to dilute, and can easily metamorphose in unexpected ways. (178)

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s perspective, as shared in these pages, can be viewed as a primer for Buddhist practitioners of some experience and depth of understanding who are contemplating a commitment to guru yoga, and a waymarker or calibrator for those already navigating the path. His nuanced pen underscores numerous hindrances, points of confusion, and frequently misapprehended concepts, encompassing samsara, karma, reincarnation, non-duality, perception and delusion, pain and suffering, with an emphasis on the importance of fully embracing and building upon foundational studies and practices.

The guru has an enormous part to play in the guru-student dynamic. When a student expresses the wish to step onto the Vajrayana path, the guru must analyse that student even more stringently than the student analyses the guru. Remember, the guru we are discussing here is not omniscient. Therefore, when a student requests high teachings, the guru is compelled to ask questions like: “Have you studied Madhyamika? Have you studied Goenka’s vipashyana? If you aspire to follow Tibetan Buddhism, it’s important to be aware of its political history: have you read about the political history of Tibet? Were you educated in a Jewish or a Christian school? Were you brought up to respect Confucian values? Have you completed Ngöndro? If you have, what does ‘completed Ngöndro’ mean to you?” (183–84)

From pinterest.com

Poison is Medicine offers a much-needed debriefing after the sangha scandals of recent years, supported by a clear statement on the basic principles of the Vajrayana view, and an open and candid critique of the role of guru and disciple. It represents an antidote that is firmly conceptualized by uncompromising and sharply didactic sketches of the history and contexture of Tibetan Buddhism, with critiques of Tibet’s traditional social structures and monastic culture that are pointed and justified. Although Rinpoche’s arguments are necessarily expressed from a dualistic standpoint, he always brings along the ultimate non-duality spoken in the language for the masses—those of us far from awakening:

The essence of the Vajrayana’s message is that poison is medicine just as it is, with nothing added and nothing taken away. I hope and pray that none of you ever lose your enthusiasm for and curiosity about this glorious, brilliant and incomparable path.

Poison is Medicine is freely available for download from the websites of Siddhartha’s Intent and Khyentse Foundation in EPUB and PDF formats.

Born in Bhutan in 1961, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche is the son of Thinley Norbu Rinpoche and was a close student of the Nyingma master Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910–91). He is recognized as the third incarnation of the 19th century Tibetan terton Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, founder of the Khyentse lineage, and the immediate incarnation of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö (1893–1959). His projects and initiatives include Siddhartha’s Intent, an international collective of Buddhist groups supporting Rinpoche’s Buddhadharma activities by organizing teachings and retreats, distributing and archiving recorded teachings, and transcribing, editing, and translating manuscripts and practice texts; Khyentse Foundation, established in 2001 to promote the Buddha’s teaching and support all traditions of Buddhist study and practice; 84000, a non-profit global initiative to translate the words of the Buddha and make them available to all; Lotus Outreach, which directs a wide range of projects to help refugees; and more recently The Lhomon Society, which promotes sustainable development in Bhutan through education.

See more

Poison is Medicine (Siddhartha’s Intent)

Poison is Medicine | Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche’s New Book (Khyentse Foundation)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global

Being a Rinpoche: A Conversation with Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche

On Being Brave: Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche on Technology and the Dissemination of the Dharma

A Buddhist Vision for Education Reform: The Blue Lion Preschool, Inspired by Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

Related news reports from Buddhistdoor Global

84000 Founds Assistant Professorship in Buddhist Studies at the University of Toronto

84000 Partners with UC Santa Barbara to Translate the Tibetan Buddhist Canon

Khyentse Foundation Announces New Green Tara Sadhana eBook

84000 Launches Special Edition of The Hundred Deeds Sutra Illustrated by Children in Lockdown

Khyentse Foundation Launches New Initiative to Translate the Works of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo

Khyentse Foundation Announces 2020 Fellowship Award for Buddhist Monk Ven. Wei Wu

Khyentse Foundation’s Kumarajiva Project Marks 2nd Year with 7 Buddhist Texts Translated into Chinese

Khyentse Foundation Funds Tibetan Buddhist Studies Chair in Munich

UPDATE: Lighting the Mahabodhi Project Draws Closer to CompletionRelated features from Buddhistdoor Global