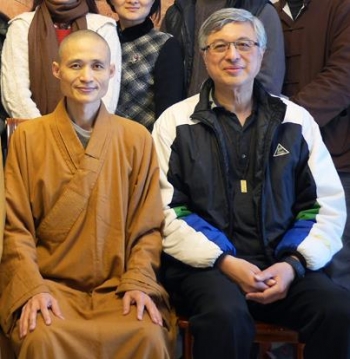

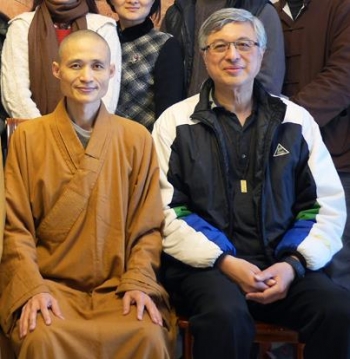

Householder Jingtu (Thomas Hon Wing Polin) with Ven. Jingzong in Shenzhen, March 2014. From Householder Jingtu.

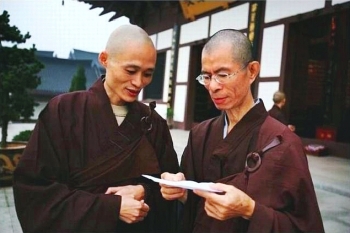

Householder Jingtu (Thomas Hon Wing Polin) with Ven. Jingzong in Shenzhen, March 2014. From Householder Jingtu. Ven. Jingzong (left) and Ven. Huijing (right), teachers of Pristine Pure Land. From http://plbtw.wordpress.com/.

Ven. Jingzong (left) and Ven. Huijing (right), teachers of Pristine Pure Land. From http://plbtw.wordpress.com/. Amitabha and his host of 25 bodhisattvas descend to take the devotee to the Pure Land. From Householder Jingtu.

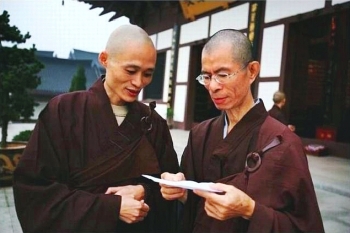

Amitabha and his host of 25 bodhisattvas descend to take the devotee to the Pure Land. From Householder Jingtu. Ven. Jingzong (left) and Ven. Huijing (right) on Dongping Shan in Xiamen. From http://plbtw.wordpress.com/.

Ven. Jingzong (left) and Ven. Huijing (right) on Dongping Shan in Xiamen. From http://plbtw.wordpress.com/.“What does Athens have to do with Jerusalem?” scoffed the early church writer Tertullian, and in so uttering drew the battle lines between reason and faith for nearly two millennia in the West. His rhetorical question has become synonymous with the struggle by scholars and religious devotees of many traditions to reconcile two apparently contradictory instincts: the urge to rationalize and dispute versus the impulse to surrender and adore. This tension between rationalism and faith has noticeable echoes in Pure Land Buddhism, which has often been misunderstood (even by Buddhist masters) as being suitable largely for emotional, unthinking practitioners. But if the journey of Thomas Hon Wing Polin is anything to go by, it is perfectly possible for rationalists to be persuaded of the power of Amitabha Buddha’s 18th or fundamental vow: that all beings can be reborn in his Pure Land if they invoke his name sincerely.

Tom has retired from his work as a senior international journalist, but keeps busy through his Buddhist identity as Householder Jingtu. “I was a complete rationalist at the height of my career as an editor for Asiaweek and Yazhou Zhoukan. If you invited me back then to explore a faith-based spiritual tradition, let alone Pure Land, I would have laughed,” he tells me at his favorite Hong Kong coffee emporium. “My background is as rationalist and secular as they come. I studied the liberal arts at Columbia and Harvard. But in the teachings of the original, pristine Pure Land Buddhism, I discovered a cohesive, well-argued system of faith that resolved the contradictions that had bothered me. It’s far from being just about emotions or some blind belief.”

Despite a successful career, at 40 Tom began to feel something was missing in his life and commenced a “rationalistic” exploration of religions. After examining an assortment of traditions such as Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism, as well as New Age, he encountered Buddhism through reading Western Buddhist classics like D. T. Suzuki and Thich Nhat Hanh. By the late 1990s he was immersed in the Buddhist tradition, and by 2003 had formally become a Buddhist. Although he explored Theravada, Chan, esoteric Buddhism, and other schools, for a long time he had noticed that his wife seemed to be growing in happiness and peace through Pure Land practice.

“I will never forget the time when I asked a prominent master which school I should follow. He told me that as a member of the intelligentsia, I should go for Chan. When I asked him about Pure Land, he said it was mainly for emotive, touchy-feely types. The incident has stuck in my mind ever since,” Householder Jingtu recalls.

“My first encounter with Pure Land was through the ‘mixed’ form of practice, which is considered ‘mainstream’ in Chinese Buddhism,” he explains. “Mixed Pure Land is still Pure Land, and there’s much value in its teachings. It may be more open in a sense since it includes elements from other traditions like Chan, Huayan, and Yogachara. But perhaps as a result of this complexity, it fails to cohere as a school of thought and practice, and in my opinion suffers from internal contradictions.” For example, the demands of ethics, meditation, and visualization are given so much importance in mixed practice that Householder Jingtu discovered many masters could not give him a clear answer about the basic criteria for rebirth in Amitabha’s Land of Bliss, the ultimate goal of Pure Land practice.

He undertook this mixed practice for several years, but was becoming trapped in such a vicious cycle of doubt that he could no longer even recite the name of Amitabha. The philosophical contradictions in mixed practice, on top of the difficulties he had experienced in his earlier spiritual forays, flung him into a pit of spiritual despair and confusion. “It got to the point where I had almost given up hope, both intellectually and emotionally,” he recalls.

But the chance viewing of a video changed everything. It featured the original, pristine Pure Land teaching from the lineage of Master Shandao, founder of the Pure Land School in the early Tang dynasty of China. While open to other practices, this “pure” tradition affirms the primacy of invoking Amitabha’s name through sincere faith in his 18th vow, central among the 48 vows listed in the Infinite Life Sutra, the core text of Pure Land Buddhism. The 18th vow guarantees rebirth in the Pure Land for any being who recites Amitabha’s name even ten times sincerely, joyfully, and with faith, if the person has only that much time left. If people have more time, they should recite until the end of their lives. “Unlike mixed practice, pristine Pure Land is unambiguous about the criteria for rebirth and explains them clearly and coherently,” he says.

“While we respect and revere the Indian master Nagarjuna and the first patriarch of Pure Land, Huiyuan, Shandao was the lineage master who really systematized Pure Land teachings into a fully fledged school of thought and practice,” notes Householder Jingtu. However, during Emperor Wuzong’s anti-Buddhism campaigns in the late Tang, Shandao’s authoritative works on Pure Land were lost in China—even as they found a safe haven in Japan and became the inspiration for Jodo Shu and Jodo Shinshu, the dominant streams of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism. “As I delved deeper, I came to know the hidden history of Pure Land. It wasn’t until the twilight of the Qing dynasty that the Buddhist scholar Yang Renshan brought long-lost texts of the Shandao lineage, in their original form, back from Japan to China. Before then, you had a millennium of Pure Land syncretism in the Song, Ming, and Qing eras, leading to the prevalent mixed practice we see today.” Pristine Pure Land is now enjoying a revival in China and Taiwan, thanks to the efforts of the Chinese Pure Land Association, led by Venerable Huijing, who is based in Taipei, and his disciple Venerable Jingzong, abbot of Hongyuan Monastery in Xuancheng, Anhui Province.

“This pure, original lineage of Pure Land answered all the questions that had been holding me back spiritually,” Householder Jingtu explains. “Questions about the criteria for rebirth, what’s primary and what’s secondary—all flowed from the essential practice of chanting Amitabha’s name. By a stroke of good karma, I discovered that there was a small center managed by two elderly monastics right across from my home. I devoured all the videos and books of this lineage, which made so much sense to me. I sought out Ven. Huijing and Ven. Jingzong and immersed myself in their Pure Land teachings, which were based on Master Shandao’s thought. By 2010, I knew that this was the practice for me.” In 2011, he flew to Taiwan to take Refuge under Master Huijing.

Householder Jingtu’s mission now is to translate into English, and to edit, key texts from the pristine Pure Land tradition, including the three Pure Land sutras, with the aspiration that seekers in the West will find them inspirational. Many Western-born people share a theistic background. The rationale is that someone born into Christianity, for example, but searching for something else, might be attracted to Pure Land Buddhism because of its unique appeal to both faith and reason.

“If Pure Land is to take hold in the West, we need first to make the texts available in straightforward but eloquent English. The basic information on Pure Land, especially in its original form, is just not available there at the moment,” he says. “Without texts, you have nothing to start from. Next, we need teachers who are open, charismatic, and comfortable with Western people and cultures, to live in the West and build small local communities through teaching and practice.” Looking further ahead, Householder Jingtu believes that for Pure Land to become popular in the West, Western-born people will need to become teachers too.

Householder Jingtu’s story is one of a journey made whole, a spiritual trek that has come full circle. It is an inspiring irony that an editor who moved effortlessly between the intellectual circles of politics and culture should find himself immersed in a devotional tradition like pristine Pure Land Buddhism. Perhaps with assistance from Master Shandao, Tertullian’s dichotomy of faith versus reason is not so difficult to resolve after all.