Scholars and practitioners of Buddhism present and attend specific sessions dedicated to Buddhist studies, although many also appear in area studies sessions, such as the Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy, or in topical sessions, such as the Bioethics and Religion Unit. This year, I session-hopped, starting by presenting my own paper in the Theological Religions Unit (a very strange session for a Buddhist, I must say), then catching the opening hour of a Practical Theology unit that focused on ending racism. I then moved on to a unit on New Religious Movements that included an overview of the New Jedi Order (yes, some people are taking that seriously), then to the Buddhism in the West unit that featured three presentations, and finally to the Religion and Popular Culture unit, which included presentations by faculty using films, graphic novels, and television shows to teach modern undergraduates about religion. That was just Saturday. The conference runs from Friday morning through noon on Tuesday.

FEATURES|THEMES|Exhibitions and Conferences

Reflecting on the American Academy of Religion in 2018

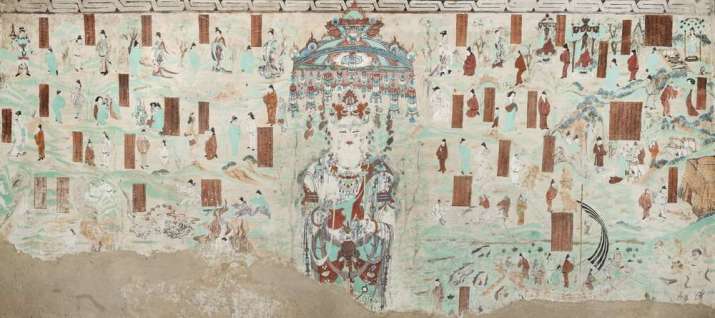

Avalokiteshvara mural in Cave 45 of Dunhuang's Mogao grottoes. From dunhuangfoundation.us

Avalokiteshvara mural in Cave 45 of Dunhuang's Mogao grottoes. From dunhuangfoundation.usThe national conference of the American Academy of Religion is huge. This year, more than 10,000 scholars and religious people descended on the Convention Center in Denver, Colorado, and the surrounding neighborhood for the conference, which hosted in excess of 1,000 panels, discussion groups, book talks, awards, business meetings, films, and workshops. The main discussion this year focused on religion in public life, as reflected in the plenary panels featuring religion journalists and some of the most public scholars on religion in America.

That tells you what it is, but not really what it is like. What it is like, in a word, is overwhelming: the convention center is a massive, multi-tiered space of atriums, escalators and long carpeted hallways. It takes 20 minutes and a boy scout patch in urban navigation to walk from one side to the other. The surrounding hotels host more sessions, and police mind the street crossings while distracted professors minding their cell phones fail to notice the signal change.

Those sidewalks and hallways are filled with scholars in tweed, twill, silk, denim, and monastic robes of every hue. People gather in clusters of animated discussion, resigned lines of caffeine addiction, or singular confusion staring in vain at signs with seemingly contradictory arrows. Somehow, folks manage to find their way from session rooms with unfailingly uncomfortable chairs to the exhibit hall with 10 rows of brightly colored and freshly printed book jackets to the massive auditoriums of the plenary sessions.

As a Buddhist, it is immediately obvious that we are a small but visible minority at AAR, which serves double duty as the annual conference for the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL). The terms “Buddhism” or “Buddhist” appear 169 times in the 401-page conference program. By comparison, “Christian” or “Christ” appear 343 times, “Muslim” or “Islam” appear 215 times, and “Jew” or “Jewish” appear only 58 times. At this year’s conference I spotted Chinese, Japanese, Sri Lankan, Tibetan, and Vietnamese robes, as well as thousands of scholars in Western attire. While some of the largest publishers in the exhibit hall are clearly dedicated to exclusively Christian texts, about half will have some books on Buddhism, and at least three are focused on Buddhist works.

AAR 2018 book fair. Image courtesy of Vanessa Sasson

AAR 2018 book fair. Image courtesy of Vanessa SassonI attend the AAR for four reasons. First, it is important to receive feedback on my own work from those who may find it useful, such as the Chinese Buddhist nun or the Danish professor who approached me after my own presentation. Second, I network with like-minded faculty and practitioners. I now have a standing invitation to visit Amsterdam and investigate how they are training Buddhist chaplains. Third, I catch up with colleagues and friends I rarely see elsewhere, such as my fellow members of the informal Buddhist Ministry Working Group and alumni of my various alma maters. Finally, I browse and collect the most recent books relevant to my work and teaching. Instructor copies are usually free and I returned with a heavy suitcase.

If I did not have my Buddhist practice to fall back on, I would certainly have been overwhelmed. In recent years I also attended the AAR in Boston, San Diego, at the unthinkably massive Chicago convention center (it is literally more than a mile wide). I learned to handle the sensory overload through various tricks, such as reviewing the program and choosing all my sessions ahead of time, and through skills gleaned from meditation practice that help me remain more aware of myself and better cope with stress. Thankfully, breath meditation can be practiced anywhere, in airports, on planes and trains, and in hotel lobbies (especially if one’s reservation has been lost!), or while waiting for a conference session to begin or end.

I believe it is important for Buddhists to continuously engage with conferences such as the AAR. There is a growing movement within the AAR, especially at the national conference, to focus more on Buddhism as a lived religion with tangible benefits for the world. No one wants to cancel the sessions on the translations of obscure Sanskrit terms in thousand-year-old manuscripts unearthed from central Asian caves (they are still very important!).

However, the focus on Buddhism as an “Oriental” curiosity for privileged Western (read: white, male, and probably Christian) scholars is gradually giving way to a new generation of passionate cultural anthropologists, contemplative studies psychologists, and Buddhist scholar-practitioners keen to exchange wisdom on how Buddhism is changing lives in the 21st Century. This is a place for Buddhists to come together to learn from one another and from other scholars and practitioners of the world’s many diverse and fascinating religions—including Jedi!

Rev. Monica Sanford PhD is assistant director for Spirituality and Religious Life at Rochester Institute of Technology’s (RIT) Center for Campus Life.

See more

Markus Davidsen on Jedi studies (Academia)

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global